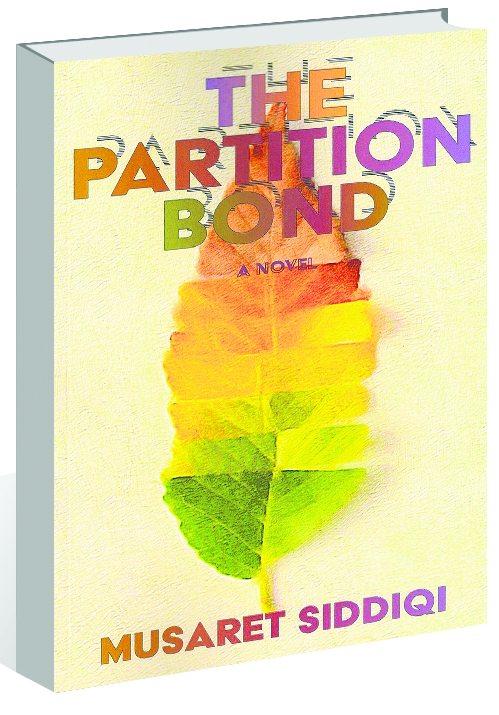

The Partition Bond by Musaret Siddiqi. Promilla & Co. Pages 314. Rs495

Book Title: The Partition Bond

Author: Musaret Siddiqi

Aradhika Sharma

Arguably one of the bloodiest chapters in the history of the world, the partition of India and Pakistan along Punjab and Bengal wreaked havoc on millions of lives. Tens of thousands of people were displaced, killed, savagely raped, and forced to convert and flee, becoming refugees in an alien land that was ironically designated to be their ‘home’.

Partition cast a long shadow on the history and fortunes of both the nations. Many who suffered loss and grief tried to forget the terrifying events, but collective memory cannot deny the bloody legacy and the events are revisited time and again. The wounds still fester.

The re-examining of this fractured chapter of the history of the subcontinent has spawned a genre of Partition literature. Modern writers and thinkers hope that the wounds caused by the wrongdoings that the nations and communities perpetrated on one another can be healed by collective penitence and forgiveness, with the hope of eventual reconciliation. Therein lies a valuable lesson for today’s fractured polity.

‘The Partition Bond’ is an account detailing the upheavals, anger, bewilderment, helplessness and hate that were suffered by the vast numbers of people because of a single political decision. Although it is a fictionalised account, Musrat Siddiqi’s book attempts to record the oral memories of the cataclysmic time, inspired by her “mother’s tales of the lost homeland in East Punjab”.

Siddiqi was born in Lahore and her narrative is of the disruption of a Muslim family uprooted from their village, Dessan Da Raja, in Jullundur and after a long, arduous journey that began from their homeland, reached their destination at 18 Jail Road, Lahore. The pater familia is Akbar, a wealthy landlord.

She speaks of how the three intertwined communities, Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims, were torn asunder as the unimaginable horrors of Partition were unleashed on a hapless population, most of whom were unwilling participants of the migration. No community was exempt of the blame of rioting and disturbance: “Amritsar was as violent as Lahore.”

Siddiqi also captures the cultural ethos of the time. The women were expected to marry and nurture their families, while the men could study and work. Roshan, Akbar’s daughter, who wanted to be a ‘lady doctor’, was married off to a suitable boy, while Saleem, her brother, studied in a college in Lahore, where he was witness to the rift among the student communities. Many of his Hindu fellow students lost their entire families when their villages were burnt to the ground. “The seeds of division sown by them (British) between the three communities through reforms such as a separate electorate had taken root… Punjab was a seething volcano.”

The book is divided into two parts that constitute different stories: the first, ‘Home’, being the story of Akbar and the migration of his family to Lahore. The second, ‘Grace’, is about Amit Narayan, a Hindu exiled from Kashmir in 1807. Amit must don the Muslim identity of Abdul Chirag since his banishment from Kashmir. After many adventures, Amit goes on to build a robust business and starts a family in Jalandhar.

The two accounts do come together in the end in a moment of shared history. However, ‘Grace’, though it is about rootlessness and exile, meanders and doesn’t add to the overall storytelling. Had Siddiqi stayed with the Partition theme, she might have produced a more relevant work.