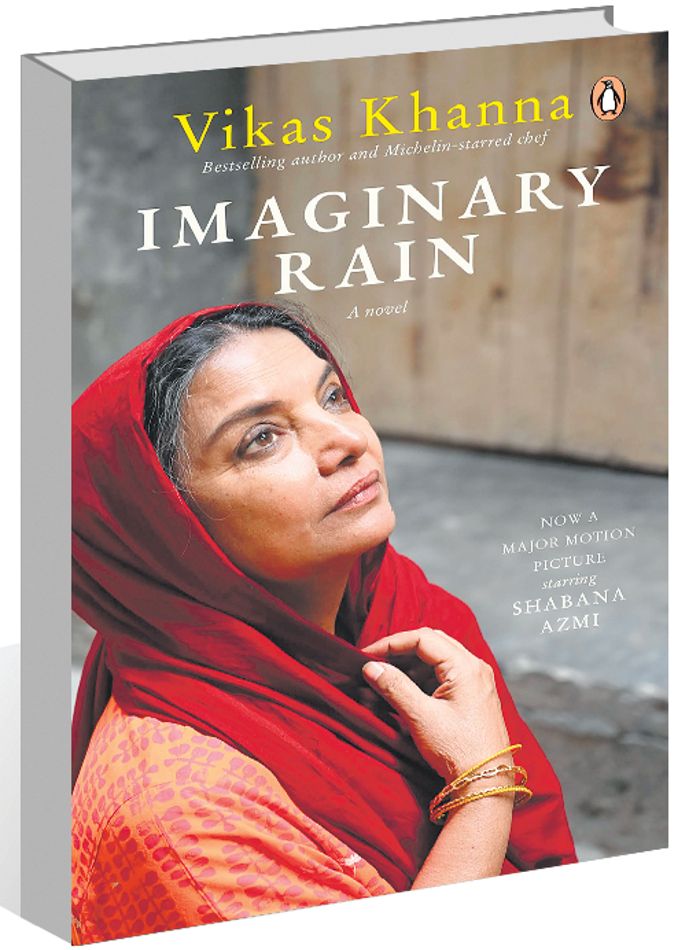

Imaginary Rain by Vikas Khanna. Penguin Random House. Pages 256. Rs 399

Book Title: Imaginary Rain

Author: Vikas Khanna

Aradhika Sharma

In Vikas Khanna’s own words, ‘Imaginary Rain’ is “a story about Indian cuisine to glorify it in the West”. Page upon page is drenched in the love for Indian food. As Prerna, the protagonist, grinds the masala, kneads naan dough, fries hot puris, and prepares the tadkas, one can almost smell the fragrances emanating from her kitchen at The Curry Bowl, her Indian specialty restaurant in New York.

The book is inspired by Khanna’s grandmother, lovingly called ‘Biji’, but evidently draws from his own experiences as a chef in New York. Khanna describes the pain of struggle of an immigrant chef. After feeding delicious meals to hundreds of New Yorkers, Prerna must shut down her kitchen. In her capable hands, Indian cuisine has conquered the hearts of the Americans, who must sadly say adieu to her food made with infinite patience and served with love.

Khanna draws heavily on his own ethos and culture of food. Like him, Prerna hails from Amritsar, and the tradition of ‘vand chhakna’ (sharing with others) is ingrained in her. She aims to give her clients “a little morsel of the Golden Temple all the way in New York”.

Despite immense pressure from the owner of The Curry Bowl, she neither compromises on her ingredients, nor does she increase the price of her food. “My wife uses the most expensive saffron to make a 4-dollar dish,” laughs Manish, her husband. Indeed, Prerna revels in “the challenge and the pleasure of feeding customers and creating a small community around her restaurant”.

The issues that immigrants face in USA are an underlying theme of the book. However, while Prerna conquers the tastebuds of the Americans with her exquisite food, Manish does not adjust well to the work culture, mostly languishing before the TV and ruing his lot. The worst sufferer is their son, Karan, who is a target of relentless bullying in school — the result of being brown-skinned in a white land.

No stranger to loss, Prerna is a patient woman, resigned to her fate, yet, ever hopeful. “The end of one thing is the beginning of another, like the seasons,” she tells her workers. Even when she loses the restaurant, she is not dispirited but goes on to acquire new skills like driving and resolves to visit her old home in Amritsar.

Indeed, after the loss of her beloved restaurant, Prerna’s past, which she had determinedly put behind her, with its bittersweet memories, resurfaces again. Flashes of memories from her childhood, when, as an orphan, she had been rescued from the life of a flower seller by her adoptive father, Karanjit, revisit. Once again, she relives her growing-up years in Amritsar where she experienced pure kindness from her father, selfishness from her petulant sister, and hatred from her grandmother, who would never eat food prepared by her “black hands”. She imbibed the love for food and cooking and lessons in generosity from Karanjit.

Khanna also talks about the rise of popularity of Indian food in the West when the market starts to witness a spike in interest in Indian cuisine. “Indian cuisine is going to explode and become more popular than ever with a higher demographic,” states a market expert, and, within a few years, it does.

The book ends on a high note, the focus shifting from Prerna to her young and successful Michelin-starred chef and nephew, Kris. This part is obviously autobiographical to Khanna, who celebrates the triumph of Indian food that has prevailed over the world, reinventing itself, while retaining its essential flavours and techniques.