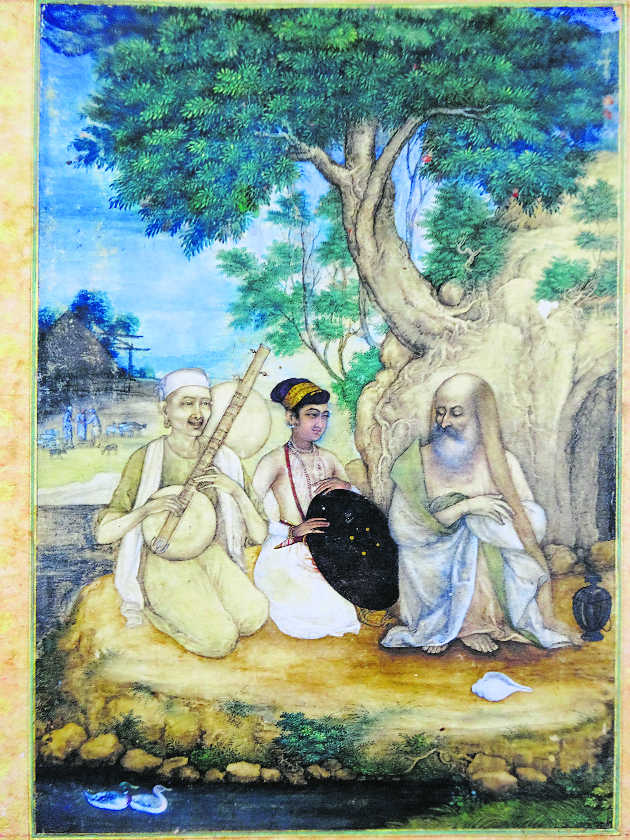

A Holy Man visited by a Prince

B.N.Goswamy

Hashiya is a word we generally use for a margin or border, and this is the word that a close friend, Mamata Singhania, chose as the title of a lively exhibition that she recently organised in Delhi under the auspices of her art gallery. Ten distinguished contemporary painters — some of them from across the border, in Pakistan, and others from home — were invited to participate with their works, but each with reference, consciously, to the hashiya: responding to the very idea. Nearly every one of them was aware of the traditional, pre-modern, work that our land is so rich in — paintings, manuscripts, and the like — but the assumption was that not every one might have paid equal attention to the margins, the surrounds. When the works came in, however, it was wonderful to see how everyone had paid close heed, for there they were — margins — informing every single work: at times expanding a theme, at others making a comment, at still others raising suggestions, evoking memories, asking questions. It was as if everyone was thinking of what the great poet, Ghalib, had said once: kuchh aur chaahiye vus’sat merey bayaan ke liye [‘more space than this I need to say what I have to say’].

However, in this context, I might turn to an essay that I was asked to write in conjunction with the exhibition. In that I veered — somewhat naturally — towards what I knew of hashiyas of the past. And of these I was able to recall a large number of bewildering variety. When, years ago, I was working on Mughal documents — farmans, land grants, yad-dashts, parwanas, and the like — one remained concentrated on the main text of the document, which was called matn, and then shifted to the margins where attesting witnesses, each identified by a name, placed their signatures or thumb-impressions: they were ‘hashiya-gawahs’. Occasionally, one came upon a document described as ‘hashiya-dar’, meaning ‘having marginal notes’; one even encountered an expression, pointing to a person on the outskirts, say of a piece of land, like ‘hashiya-nashin’: ‘sitting on the edge’. Margin, edge, border: these then are what one thinks of when we speak of hashiyas even though between them there are, or can be, distinctions; subtle differences. What, in a painting for instance, is an ‘inner margin’ to be called, as opposed to the ‘outer margin’? Does ‘edge’ lie necessarily outside of the ‘margin’, but adjacent to it, on an album page? Is it fair to designate ‘border’ strictly as something that the artist himself conceived and made a part of his painting? Fine distinctions, ambiguities, remain. Ordinarily a margin — most often floral or decorative — surrounds a painting which is the main object, but this can change. In the Chandigarh Museum, for instance, there are a few folios of a dispersed Bhagavad-Gita manuscript, in which the centre is occupied completely by shlokas from the sacred text written in local takri characters, and the margins, on all four sides, feature what might be called ‘illustrations’, related in one way or another to the text. As I said, things can be very different.

There are hashiyas and hashiyas then in Indian painting. But what come most easily, floatingly, to the mind are those that one encounters in Mughal painting, especially the ones from those splendid albums that were assembled in the period of the emperors Jahangir and Shah Jahan: the Jahangir-period Gulshan Album now in Iran, for instance, or what has come to be called the dispersed Late Shah Jahan Album. On the uncommonly broad margins of these, surrounding the main image in the centre, there are some singularly sensitively rendered figures that relate consciously to the central image: dazzling in the way they support, emphasise, help to interpret, the work. Here I have space to refer in detail just to one painting — and draw peripherally upon another — from the Late Shah Jahan album, in which the central image is that of a recluse being visited by a prince; an encounter, so to speak, between the shah and the gad’a: one a man of earthly means and the other possessed of the riches of the mind. Quietly, the painter seems to ask us to determine for ourselves who is the shah and who the gad’a in this case. Whether this or not, the holy man we see sitting under a tree out in the countryside, long hair streaming down to his knees, expression of utter peace on his face, listening to music being played on an ektara by a disciple, while a young prince sits between the two, waiting for the ascetic to open his eyes, for he has questions to ask, enlightenment to seek. All around at the same time, on the three sides of the hashiya, one sees small figures, seated or standing, six of them faqirs or seekers. Each of the ‘sadhu’-like men is a brilliant study: each of them is dressed — minimally clothed — differently; each sits or crouches in his own fashion; each of them has his own calabash by his side, evidently his sole earthly possession; each seems to be lost in thought while listening to the music being played in the centre of the painting. One of them, in fact, a young acolyte standing at bottom left, appears to have been on the point of leaving with his feet turned in that manner when he seems to have heard the strains of music and stops, turning his head towards it. Much the same happens in another painting from the same album, now in the Musee du Louvre in Paris, where seekers occupy the hashiya around the image of the Sufi in the centre. When you see these figures, a certain calm, like moonlight gently descending downwards, as the poet says — ‘yoon jaise shab ko chandani, chupke zameen par aa rahey’ — takes the viewer over.

This is what can happen in a hashiya; the margin no longer remains a margin.