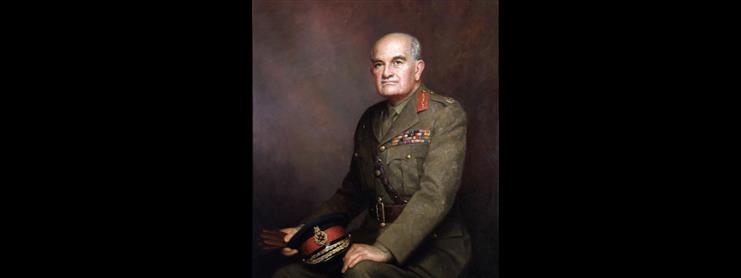

Lt Gen Baljit Singh (retd)

“I was, like other Generals before me, to be saved....by the resourcefulness and the stubborn valour of my troops.” — General William Slim about the Burma campaign, 1944

In the closing two years of WW II in the Burma campaign, Gen William Slim as Commander Fourteenth Army would emerge a votary of the dictum that “A bold general may be lucky, but no general is lucky unless he is bold”. General Slim was an intuitive master of the “operational art” and a deserving entrant in the hallowed pantheon of warlords by the virtue of exceptional military leadership skills.

Field Marshal Slim's meteoric rise was shaped by his impoverished childhood. Starting as a teacher in a local slum school, he eventually became a much-decorated soldier. Because of his exceptional leadership skills, he carved a victory out of defeat during the Burma campaign

There are three broad elements to warfare, namely the application of combat power, marshalling and movement of logistics. But above all, capable military leadership with proven battlefield experience backed by scholarship in the art and science of warfare. And the application of these elements as a judicious mix at the appropriate time and place is the crux of what is called the “operational art”.

Unlike his peers, Slim's meteoric rise was shaped by his impoverished childhood. He started his first job in 1910 as a teacher in a local slum school and later became a clerk in Stewarts & Lloyds. He learned an early lesson that assiduous hard work is the bedrock of success in life.

Within days of commencement of World War I, Slim qualified for War Time Commission in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment. As a rookie lieutenant during the Gallipoli offensive, he led his platoon courageously against the Turks. In the process, Slim was seriously wounded but got a the Military Cross (MC) for his gallantry. After eight months' of hospitalisation in London, he was back on the battlefield with renewed vigour and was Mentioned-in-Dispatches twice for bravery in the battle of Baghdad. He was again wounded and evacuated to Bombay. Post recovery this time he was granted permanent commission in the Indian Army, his alma-mater hereafter.

A battlefield hardened and proven combatant, Major Slim now focussed his energies on acquiring military scholarship. He topped the merit list for entry to Staff College, Quetta and topped the class on graduation. He then served at Army Headquarters, Delhi, before moving to Staff College, Camberley (UK), as an instructor. Given his background for hardwork and merit, three years later he was the natural choice for the inaugural course at the Imperial Defence College (UK), in 1937.

Now promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and given command of 2/7 Gurkha Rifles, Slim was quite pleased with it because in Gallipoli he had been “fascinated by the fighting qualities of the little mountain men from Nepal.” Two decades later, Slim’s memoir, Unofficial History was, in part, a sensitive eulogy of his Gurkha comrades.

At the commencement of World War II, Slim had, by the dint of his courage and application of mind for six years on the art and science of warfare, acquired a reputation for professional excellence among his peers and superiors. This was further bolstered as he successfully led a brigade in Eritrea. This was followed by command of 10 Indian Infantry Division for the capture of Iraq and Iran. It got him the Distinguished Service Order, which is second only to the Victoria Cross (VC).

When Japan joined the Axis Alliance with their devastating aerial blitzkrieg over Pearl Harbour on December 4, 1941, almost the entire armed forces of India, Australia and New Zealand had been committed to war in Europe, Africa and the Middle East. As we now know, Pearl Harbour was a prelude of the Japanese two-pronged grand design viz, defeat of China once and for all (Operation Ichi-Go) and the March to Delhi (Operation U-Go).

The War Office in London at that time had little choice but to create from scratch a rag-tag Burma Corps (Burcor) comprising 1 Burma Division. It was hurriedly patched together from Territorial Battalions, two Indian Mountain Artillery Batteries, and eight antiquated Air Defence Guns. This unit was soon to be reinforced with 17 Indian Infantry Division which at that time was on the high seas heading for Egypt.

A World War I veteran Maj-Gen John Smyth, VC, MC, wanted the 17 Division to have its first battle along the Sittang River but both British PM Winston Churchill and Commander-in-Chief of American-British-Dutch-Australian Command Archibald Wavell, desperate for victory after a series of defeats elsewhere, over-ruled Smyth and ordered him to “Go forward”. That he did and despite several brilliantly fought encounters, he and his men could not stem the winning streak of the Japanese offensive.

On February 23, 1942, Smyth was faced with the dilemma to either accept destruction of his two brigades in contact with the enemy or blow the only bridge over River Sittang and thus impede the Japanese advance and delay the fall of Burma. He chose the latter.

In the event, 17 Division was reduced to one effective brigade and Smyth was “sacked”. A brilliant career ended in unwarranted disgrace on March 2, 1942.

As though prompted by prescience, the War Office had already moved Slim to Rangoon. At this juncture he took up Command of Burcor manfully but the challenge of stemming the Japanese offensive was beyond the means at his disposal. The best he could do was to prevent a rout and destruction and so he dexterously launched them on “the Indian Army's fighting withdrawal of 1,800 kilometres, the longest in the history of warfare” crossing back to India on May 24, 1942. In General Stilwell’s words, “They had got a hell of a beating but they had not been disgraced.....Slim was proud to have commanded them and was determined that one day they would go back.”

The Japanese, too, were stretched beyond their capacity for the march to Delhi and instead pulled back along the Irrawaddy River line to regroup for another push. Meanwhile, Slim was promoted to command the newly created Fourteenth Army with the mandate to recapture Burma with his cosmopolitan army of 12 divisions; seven were Indian, two British and three from colonies in Africa besides ample air support from two components of the US Army and Allied Air Forces in Assam (a far cry from the Burcor). Meanwhile, the Japanese Burma Army had also grown from four to eight divisions.

By March 1944, the stage was fully set for an Armageddon such that “nowhere in WW II did the combatants fight with more mindless savagery”. Slim had decided that he would lure the Japanese to come forward on the ground of his choosing, cripple them severely against his well entrenched defences from Imphal to Kohima and thereafter go on the offensive to inflict total defeat. As anticipated, the Japanese took colossal casualties and were forced to retreat in total disorder in July, 1944. By one estimate from this opening phase of Slim's offensive “.... of the 150,000 Japanese troops only 14,000 survived”!

Promoted General and Commander All Allied Land Forces South East Asia, Slim's next phase was a masterpiece of the operational art opening with a daring and deep outflanking manoeuvre to capture Meiktila, leaving the bulk of Japanese Army in the Irrawaddy loop with close to zero logistic support. And that set the stage for 17 Division to make a dash for Rangoon and hoist the Union Jack from where they had been evicted by the Japanese two years earlier on February 24, 1942. A great military triumph by any yardstick.

And of that dramatic moment, a nineteen-year-old lance corporal wrote home “I see him (Sic.Slim) clear, with that robber-baron face under that Gurkha hat, and his carbine slung, looking a rather scruffy private with a General's tabs, which, of course, is what he was.”

Penning his most charming memoir, the Unofficial History, Slim recounts that once as a cadet he sat pouring over the text of “Principals of War” when an old Sergeant-Major going past him checked his stride and said “Don't bother your head about all them things, me lad. There's only one principal of war and that is this. Hit the other fellow, as quick as you can, and as hard as you can, where it hurts him most, when he ain't looking”.

That advice was to guide Slim throughout the Burma campaign in the shaping of a “defeat into victory” such that the military historian Lt Gen Sir John Kiszely would most deservedly call Slim “perhaps the Greatest Commander of the 20th Century”.

Join Whatsapp Channel of The Tribune for latest updates.