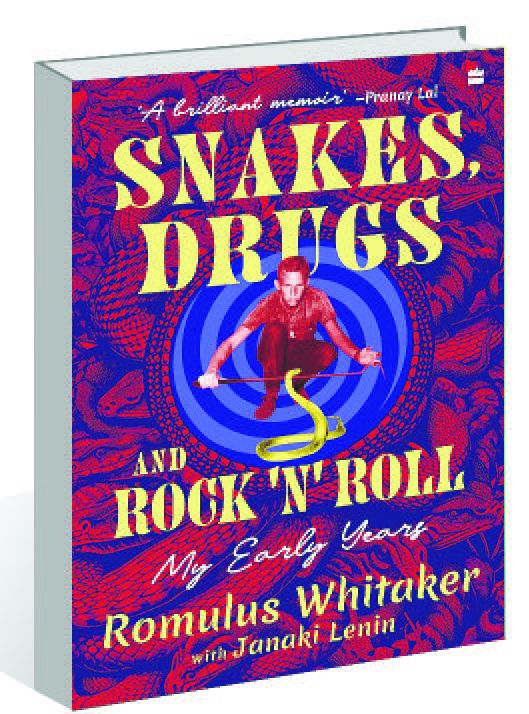

Snakes, Drugs and Rock ’n’ Roll by Romulus Whitaker, with Janaki Lenin. HarperCollins. Pages 400. Rs 699

Book Title: Snakes, Drugs and Rock ’n’ Roll

Author: Romulus Whitaker, with Janaki Lenin

R Umamaheshwari

Padma Shri awardee Romulus Whitaker is much celebrated, documented and awarded, but much of his hitherto unknown human side comes alive unapologetically in the book (co-authored with his wife, Janaki Lenin) ‘Snakes, Drugs and Rock ’n’ Roll’. The autobiography partly gets its title from a book — ‘Snakes of the World’ by Raymond L Ditmars — his mother, Doris, gifted him. She also helped him keep snakes as pets, turning an old aquarium into a terrarium. At the same time, she extracted a promise from him to not kill a snake.

Fast-paced, the book revels in images (verbal and a few virtual ones put in); anecdotes pour forth like a river during monsoons. You can pick up a page in any of the chapters (26 of them, divided into two sections: ‘Growing Up’ and ‘Finding My Feet’) and relish vivid experiences, sometimes marred by way too much detailing. This account of just 20-odd years (he was born in 1943 at Queens, USA, and the book ends in the late ’60s) shows what a picturesque adventure his life was: keeping a pet python at boarding school (Kodaikanal, Tamil Nadu); hunting snakes with commercial hunters; brother Daniel teaching him skinning of birds and introducing him to Salim Ali’s ‘The Book of Indian Birds’; being introduced to William Haast and the Miami Serpentarium at the school library: stuffing “about fifty species” of birds (packed in a box “cushioned with cotton” for a trip to his home in Bombay), which he would later donate to a museum in Seattle; learning taxidermy at Mysore; working as a seaman; working at a serpentarium; being enlisted in the US army; drugs and hallucinating!

Equally fascinating was his extended family: Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya (‘Amma Doodles’, as he referred to her) and Harindranath Chattopadhyaya (‘Baba’) as his grandparents (their son Rama Chattopadhyaya was Rom’s stepfather), and an artist aunt (Elly) who was married to Abdul Razzack, the chief technical and industrial adviser to the governments of the Nizam of Hyderabad in India and the King of Jordan.

In the Introduction, Rom confesses that he grew up hunting the very species that he has since spent decades conserving. “In an autobiography, authors are caught between extolling their virtues and achievements, and camouflaging their raging egos. It would be dishonest to chronicle the awards and applause, and airbrush my blood thirsty past off the record… By revealing my bloody hands and early love of destruction, whether it be of animal life or explosives, you, the reader, can see the real me with all the warts…”

Some heart-warming memories in the book include a poem that Harindranath Chattopadhyaya penned (in 1948) for Rom (“a blue-eyed angle-boy — and blonde!”) and his sister Gail. Then his ‘Amma Doodles’, who gifted him, on his 12th birthday, a “beautiful pelt of a snow leopard that Sheikh Abdullah, her colleague in the pre-Independence Indian National Congress, had gifted her a few years earlier…”

In ‘The Year of Vices’, you see him buy a pet python from the Crawford market in Bombay, travelling with it in a train to Kodaikanal, besides his fishing expeditions at Powai and his tryst with explosives. There is a funny incident when his python goes missing and he writes of the reactions of his neighbours (in Bombay) as he asks each of them if they had seen his ‘pet’ (finally found shedding his skin at home).

He writes in ‘Drafted: One, Two, Three, What are we fighting for?’: “I didn’t want to kill people or be blown up in Vietnam.” Rom tried to evade enlisting thus: “I have a bad back. A lump in my foot prevents me from wearing boots…” It didn’t work. His stint in the army ended in 1967. Having spent six years in the States, the country of his birth, he returned to India on board a ship with “500 dollars worth” of rattlesnakes. He notes, “The Indian Wildlife Act was still a decade away and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), which governed the movement of animals across national borders, hadn’t come into being yet... I was home at last.” Bill Haast would inspire him to start something similar in India. ‘The Epilogue’ suggests there may be a sequel on “the adventure of my wildest dreams”.