|

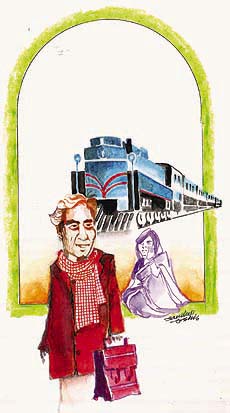

Pashupatinath winks at Kaalu

Singh

By Baljit Kang

LIKE fishermen,  hard-bitten travellers too have their stock

of tales. Wild, wacky stories to be swapped over a mug of

beer or summer evenings or while waiting by the roadside

for a seemingly imaginary bus to arrive. A sometimes

subscriber to the breed, my stock of tales, while not

exactly overflowing, has its element of drama and colour.

Among my favourites are the unexpected adventures of one

Kaalu Singh. hard-bitten travellers too have their stock

of tales. Wild, wacky stories to be swapped over a mug of

beer or summer evenings or while waiting by the roadside

for a seemingly imaginary bus to arrive. A sometimes

subscriber to the breed, my stock of tales, while not

exactly overflowing, has its element of drama and colour.

Among my favourites are the unexpected adventures of one

Kaalu Singh.

Kaalu’s story opens

in the autumn of 1987, an unexpectedly good year for our

hero. After years of nail-biting suspense, punctuated by

breaks to ring in a string of daughters, Kaalu’s

patron-saint Lord Shiva, had finally smiled down on his

simpleton bhakta in a dusty village near Sambhal

(Moradabad). Kaalu’s poor-peasant household was

blessed with a son. And Kaalu, in turn, was now

honour-bound to hold up his end of the deal.

But even the gods must bow

before the demands of the land. What with a rich harvest

of paddy ripening in Kaalu’s two acres, and the

accompanying obligations of arhatia loans to be

paid back. So it wasn’t until the middle of October

that Kaalu could find the time to keep his tryst with his

god, a pilgrimage to Pashupatinath’s seat in distant

Kathmandu.

Once begun though, Kaalu

set to the affair with a remarkable singularity of

purpose. A spangling new hand-bag and blanket were

purchased from the weekly market in neighbouring Hathras.

The handknit pullover and muffler that his wife had

worked on late in her pregnancy were dusted out and

readied for use. Along with a warm English-style coat, a

throwback to the salad days of their marriage, when money

had been less of a problem.

Throw in a spare kurta,

a cotton bag of roast chana and last-minute

cautions by his worried wife at the railway station at

Moradabad, and Kaalu Singh, who’d never wandered

further afield then the ghats of the Ganga at Garh

Mukteshwar, was on his way to the mystical kingdom of

Nepal.

An improbable pilgrim, but

the gods beamed approval. At least up until Lucknow,

where Kaalu Singh, must change trains for the remainder

of the journey until the Nepalese frontier at Sanauli.

When his train rolled into Lucknow station with the

punctuality of a chowk clocktower it was to the discovery

that its more time-bound connecting number was beginning

to roll out. With a fortitude born of long years of

deprivation Kaalu watched it inch past, conscious that he

could jump on, but that without a connecting ticket this

would only engender unpleasantness, possibly a fine.

Besides, there was sure to be another train along soon.

Till then he could fix himself some breakfast.

Kaalu had been waiting for

under 15 minutes when a polite stranger came up to him

and asked him to keep an eye on his considerable baggage

while he went into the men’s room. Afterwards, as if

in recompense, and over Kaalu’s protestations, he

insisted on buying Kaalu a cup of tea, while they waited

for the train to the frontier.

It was only in the fitness

of things then that when Kaalu wanted to go the toilet,

the stranger offered to keep an eye on Kaalu’s

single bag. Not that Kaalu could not have taken it along.

But a certain propriety must be maintained.

And it was, even when

Kaalu returned less than a minute later to discover he

had been taken for a ride, bag, blanket and all. Though a

trifle saddened, Kaalu decided, nevertheless, to continue

his journey. This time in circumstances more in keeping

with that of a pilgrim. So when Kaalu Singh arrived in

Kathmandu two days later it was with but a single worn

shirt on his back, (he had conservatively kept his new

clothes aside for the sacred darshan) and a little money

in his pocket.

But if Kaalu was worried

he did not allow it to show on his face as he strode off

the bus in the capital’s Ratna Park and stretched

his limbs in the balmy mountain air to get his

circulation going. It was late afternoon by then, and

after 16 hours in a cramped bus over winding mountain

roads, Kaalu would have liked nothing more than

stretching out in the sun even if it were in the inviting

lawns of the park itself, for the remainder of the day.

He would offer puja at the more appropriate hour

of sunrise. But his eroding stock of money and lack of

warm clothing militated against his plans. So when the

man at the ticket window told him there was a bus back to

Sanauli at 8 PM a seat was available, and Kaalu could

easily make the round trip of the Pashupatinath Temple

and back in the time remaining with him, Kaalu Singh paid

the deposit on the ticket. Now only the streets of

Kathmandu lay between Kaalu and his patron god. And the

pilgrim could hardly wait. For almost the first time

since he had started, Kaalu’s face showed a trace of

emotion as he strode up to a well-built elderly Sikh, a

familiar face in this foreign street, to enquire about

the way to ‘Pashupatinathji’.

But Kathmandu, it would

appear, had more imperious plans for Kaalu Singh. The

annual South Asian Association of Regional Cooperation

conference was to open in the city in two days. And,

given the backdrop of militancy in the region and that

the heads of state of all Nepal’s neighbours,

including Big Brother India, would be present, the

city’s inadequate police force had been whipped into

a frenzy. As if that were not enough, Indian intelligence

agencies had swarmed in — foreign hands sounding

ominous warnings of other foreign hands out to get Prime

Minister Rajiv Gandhi, heightening the paranoid

atmosphere. Till, in sheer panic, the police acted with

the autocracy that is the hallmark of the kingdom.

Anybody who could not

satisfactorily explain his presence was to be expelled

from the city for the duration of the conference.

‘Militant’ ethnic groups were to be questioned

and, even if remotely suspect, incarcerated. Thus, within

a matter of hours, much of the city’s sizeable Sikh

population hit up against a quite unexpected barrier, a

set of steel bars. As did many ethnic Tibetans, (an

improbable story had the Chinese trying to assassinate

Rajiv Gandhi by infiltrating the local Tibetans. The

truth was more pedestrian, the King feared Tibetan exiles

might embarrass him by raising the Tibet outside the

venue) Sri Lankans. Even an Iranian was imprisoned to

give the detainees a more cosmopolitan character.

As luck would have it, at

the very moment that Kaalu Singh chose to approach his

Sardarji for directions to Pashupatinathji, plain-clothed

policemen were also moving in for the kill. And before

Kaalu could pop his single question, they had popped

theirs. So, while Kaalu waited impatiently in the wings,

the Sardarji, a prosperous local transporter mollified

his interrogators.Questions over, both the policemen and

their intended victim were planning to move on when

Kaalu, unwittingly drew their attention to himself.

"Sardarji,

Pashupatinathji...", Kaalu began hesitantly to the

Sikh’s departing back.

The words were like nectar

to a bee. The plain-clothed policemen who’d just

registered the bedraggled figure now swung back.

‘Tum kaun’ (Who

are you?)

‘Main Kaalu Singh.

The Sardarji, sensing

Kaalu’s imminent plight before Kaalu himself did,

returned to stare at the poor farmer in perplexity,

asking him what it was he wanted. This unwitting

admission of lack of acquaintance sealed Kaalu’s

fate. After that both the Sikh’s plea that the dark,

clean-shaven Kaalu was an improbable Sikh still less an

assassin, and Kaalu’s own rambling explanations of a

son in Sambhal and a god in Kathmandu cut little ice.

Instead Kaalu, the latest entrants to the ranks of the

Khalsa, found himself staring out of the imperial Durbar

Square lock up, towards Pashupatinath — so near and

yet so far.

Still, unwitting convert

that he was, Kaalu soon had cause to identify with his

new faith. For once he discovered that he might be in the

lock-up for a few days and that inmates of the lock-up

had to arrange for their own, high-priced, food from

outside, he sensed that the choice before him was

starving here or — should he spend his remaining

money — starving out on the streets of Kathmandu.

And, too proud to contemplate the latter, he refused to

eat.

But by dinner time, the

Sikh sangat of Durbar Square lock-up had already

realised the plight of the dark and lean and not-so-young

Khalsa in their midst. And, as it was unthinkable that

the Singh be permitted to starve so soon after his public

demonstration of allegiance they, in turn, pitched in

with that other venerable Sikh institution — the Guru

ka langar.

For the two days that he

was in Durbar Square, Kaalu was treated to a generous

fare of Nepali food and anti-Nepal grouses. Afterwards,

the same mysterious logic that saw it fit to incarcerate

Kaalu, now singled him out for dispatch to the

high-security Central Jail to sit out the remainder of

his sentence while lesser Sikhs were dispatched to the

neighbouring open-air Bhadragol, reserved for

less-demanding detainees.

Late on the evening of the

seventh day of his arrival, Kaalu finally walked out of

the gates of Bhadragol, a free man at last. There was no

ceremony to his exit, no grins or congratulatory

backslapping. Instead, with a singularity of purpose

honed to an edge over the past days he strode

purposefully out to the local bus stop, and onwards

— to keep his now long overdue date with

Pashupatinathji.

Thanks given, he

back-tracked to the fledgling gurdwara at Naya Bazaar to

spend the night. He was up at dawn to attend morning

prayers at the gurdwara. It was when he was accepting prasad

that Kaalu manifest the only visible trace of emotion

— gratitude, faith, recognition rolled in one. Later

that day he caught the bus out to the Indian border.

|

Majestic forefather of modern

bicycle

By Jupinderjit

Singh

A CLASSIC

bicycle made of wood and iron dating back to 1870 in one

of the most sought after antique pieces at the Museum and

Arts Gallery of Punjabi University, Patiala.

Visitors irrespective of

age are bewildered at the very sight of this primitive

model of a bicycle. Children and elders alike insist upon

having just one ride on it. Even VIPs who keep

frequenting the university to attend some function have a

look at this "majestic" forefather" of the

modern bicycle. So it’s little wonder remarks

praising this bicycle dominate the visitors’

comments about the museum recorded in a register.

This masterpiece

functioned like that of a modern three- wheel cycle of

children. Without any brakes, chains and axle, the

functioning of the old model is completely different from

what we have today. The wooden pedals are permanently

fitted in the front wheel instead of the centre axle, as

in the modern version. For bringing the cycle to a halt,

one had to just stop pedalling.

Besides having an

interesting history, the cycle is also an excellent blend

of Indian handicraft and the technology brought in by the

Britishers. The wood and iron used in the bicycle has not

worn out even after more than one and a half centuries.

The spokes of the wheels

are of wood while the outer covering of the wheel is of

iron. Beautiful carving has been done on the wooden

pedals as well as the handle.

The cycle could be used by

persons of different heights as the saddle can be adjusted

to suit the length of the person’s legs. Above all

the benefits, is the fact that this cycle with iron

wheels could never get punctured.

Dr Saroj Chaman, incharge

of the Museum and Arts Gallery, informed that the cycle

was donated by Hazara Singh, Director, Publication

Bureau, Punjabi University, nearly 10 years ago.

He had got the cycle from

the owner of Krishna Engineering Works, a cycle

manufacturing unit in Patiala. The forefather of the

owner of the factory used to ride this cycle daily from

‘Beghowal’ village to Ludhiana in 1870. It is

said that the man was inspired to manufacture such a

cycle, a rare commodity in those days, when he saw some

Britishers riding such a mode of transport. As he could

not afford to buy the cycle, he understood the

functioning of the cycle from one of his British friends

and designed his own model. This cycle remained a proud

possession of the family for generations. During this

time, innumerable offers from various cycle manufacturing

companies came about purchasing the antique model at any

desired cost. However, the family did not yield to the

lucrative offers as the company owners would have

projected the cycle as if manufactured way back by their

own company.

Hazara Singh, who had

donated a number of antique pieces to the university, was

able to persuade the family to donate this ancient cycle

model to the Museum and Art Gallery.

Unfortunately, while the

museum deserves praise for preserving the cycle. The

absence of any note detailing the historical background

of the cycle is deeply felt by the visitors.

|