Fashion

20th

Century’s sunshine sector

In the

20th century Indian fashions have swung from the

traditional to the western and now seem to be going back

to their roots with leading designers re-elevating the

textile craftsman to the lofty status he enjoyed in the

pre-British era, says Manisha Diveshwar.

AN old man peered through his

spectacles at the charkha he was spinning. Clad

only in a loin-cloth, he spun, thread by thread, inch by

inch, what was to become India’s most eloquent

symbol of freedom.

The khadi that Gandhiji wove became

a unique and effective form of protest, a gift that

helped rediscover the rich textile heritage and the

diversity and depth in the weaves and crafts of India. The khadi that Gandhiji wove became

a unique and effective form of protest, a gift that

helped rediscover the rich textile heritage and the

diversity and depth in the weaves and crafts of India.

It was a process of

re-discovery. Over the years, the British worked on a

plan of altering India’s textile trade and changed

its role from the largest supplier of textiles to the

world to the largest importer of English cloth. Writes

leading designer Ritu Kumar in her book, Costumes and

Textiles of Royal India," A century of colonial

rule rang a death knell to traditionally produced Indian

fabrics which almost went extinct."

Gandhiji’s master

stroke of elevating the charkha to a national

stature was not just a symbolic protest but also

showcased the rich textile heritage of India which, over

the years, had been systematically plagiarised by the

British who began replacing the skills of Indian

handicraft workers with cheap imitations made in the

mills of Birmingham.

The charkha

changed all that and once again the Indian textiles

started to get revived. So much so, 50 years on, today,

India is now being considered a storehouse of designs by

leading couturiers of the world. No other country has on

offer the variety of fabrics, weaves and crafts as India.

It is not surprising that these are being sought after by

designers in the world’s fashion capitals like

Paris, London and New York.

The Indian fashion scene

has evolved at breakneck speed in the last decade of this

century. Though very much a part of the lifestyles at the

turn of the century, during the Raj days fashion used to

be the exclusive domain of the aristocracy.

The complete adoption of

Western dress occurred only in the beginning of the 20th

century when the Indian royalty changed its attire. Ritu

Kumar writes, "The British idea of civilised dress

codes caused a crisis of identity which unfortunately

shifted India’s royal family’s preference for

foreign fabrics, and patronage to its weavers was

withdrawn."

The

colonial influence

By the beginning of the

20th century, maharajas and nawabs had begun to

incorporate European styles in their poshaks. For

example, at state functions, they wore British coronation

robes duly decorated with stars and medals held together

with cords and jewelled broaches  on

their traditional clothing. Interestingly, the turban,

topee and jootie still remained. on

their traditional clothing. Interestingly, the turban,

topee and jootie still remained.

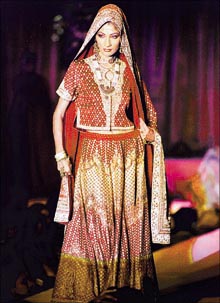

The zenana,

however, continued to be in purdah. Her zardozi

ghaghras and duputtas handworked with beads

and jewels, duly complemented the heavy brocade and gota

on sarees with intricately designed jewellery.

By the 1920s, the

younger princes were beginning to adopt completely

western wear, having given up their sherwanis, achkans

angarkahas and jamas. The queens and

princesses maintained their traditional attire for the

simple fact that their husbands were interacting socially

with the British and their colourful, heavy ghaghras

were a perfect foil for the lighter, western-style

dresses the men wore.

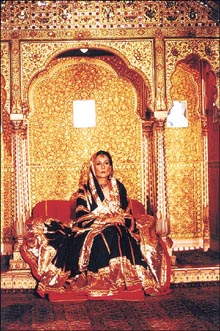

In the late 1930s when

women started to break loose from the traditional

clothes, in came the formal saree. The fashion statement

was again made by the then queens and princesses led by

Maharani Gayatri Devi of Jaipur whose chiffon sarees,

with or without borders and delicate jewellery, became a

craze with women.

Comical

ensemble

With passing years, the babus

too had a change of mindset about clothes. Out went

the kurta and in came the stiff white cotton shirt

with cuffs worn over a dhoti, a dark coat, white

socks, shoes and an umbrella. This completed what Ritu

Kumar calls a "Comical ensemble".

The result of this

predilection for western wear was that traditional

techniques of patterning, spinning and weaving by master

craftsmen began dying. To an extent these masters had

also themselves to blame as they jealously guarded the

secrets of their craft and never taught them to

outsiders.

The result was that the

cheap initiations from Britain virtually snuffed out

exclusive Indian craftsmanship in textiles. The

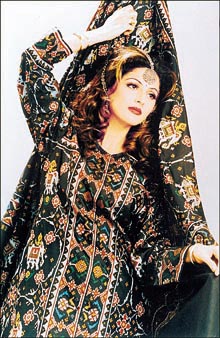

traditional designs of Srinagar, Varanasi, Surat

Murshidabad and Ahmedabad began to get mass produced in

England. Even the stunning Kashmiri shawls were imitated

in Edinburgh and Norwich with the help of modern machines

and the original lost out to competition by the

mid-twentieth century.

Ritu Kumar says,

"Two arts that died are the textiles of Kashmir

woven in the kanni weave more popularly known as

the jaamawar shawl and the ultra-fine cotton

muslin of Bengal. However, they were lost but fortunately

they didn’t die."

It was in protest

against such British practices that khadi became the

symbol of Independence in 1920 and all imported fabric

began to be burned. Khadi kurta over khadi dhoti

or pyjamas or and Gandhi cap for men and khadi

sarees for women became the dress code of all Indians

during those turbulent times. With such an emphasis on

Indian fabric, the vast legacy of textile craft was

revived within two decades of India’s Independence.

The revival of

India’s traditional textile arts and techniques was

pioneered by Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay. Looking for ways

to embellish her khadi sarees, she broke the cast

taboo and went about organising weavers and craftsmen.

Ritu Kumar revived the Zardozi, Pranavi Kapur the

muslin khadi and Calcutta designers Mona-Pali the kantha

work and its motifs on sarees.

Experiments

with the saree

Views on how the saree

evolved differ. Ritu Kumar says a new dimension was given

to the saree by Rabindranath Tagore’s sister in-law

Yanodanandini in 1870 by wearing it over a petticoat with

a blouse to match. Lina Luyton, in her book Sarees of

India, says the saree can be traced back to the

Brahmo Samaj days.

Whatever the exact date, the fact is that

the saree started enjoying a cosmopolitan acceptance

across different regions as British dresses were

restrictive and unsuited to Indian conditions. Whatever the exact date, the fact is that

the saree started enjoying a cosmopolitan acceptance

across different regions as British dresses were

restrictive and unsuited to Indian conditions.

From the early part of

the 20th century, women’s experiments and

innovations only went so far as increasing or shortening

the length of the pallav, or wearing it elegantly over

their heads or, with the passage of time, just

nonchalantly throwing it over the left shoulder.

Vandana Bhandari,

assistant professor, at National Institute of Foreign

Technology (NIFT) says, "Unlike the saree, the

blouses began to be experimented with. When women in the

West wore highnecks, fluffs and flounces, Indian

women’s blouses had lace fluffs on the neck and the

sleeves. Necks went higher or lower according to the

western fashion. Long sleeves or short ones, frills and

sleeve edges were dictated by the West."

After Independence, the

erstwhile kings and princes lost their British patronage

and they in turn withdrew their patronage to the karigars

who began languishing in poverty. Several

attire-related arts which thrived earlier were in danger

of getting lost. This, coupled with the fact that most of

India’s crafts and weaves were highly

time-consuming, made the end product out of reach of the

common man.

According to Ruby

Kashyam, convener, Publica-tion Department of NIFT, some

of the few such near-casualties were the Patan Patoles

from Gujarat, the ikat from Orissa and Andhra,

the Baluchars and Jamdanis from Bengal, the

Paithani from Maharashtra and the brocades from

Benaras.

Post-Independence

generation

After Independence,

women who had taken part in the freedom movement entered

politics and the first signs of social change began

appearing on the horizon. They became more confident in

their roles outside the confines of the kitchen and

gradually started looking for more practical and

convenient garments.

This

paved the way for the Punjabi salwaar-kurta. It

was a convenient and comfortable wear, well within the

confines of modesty and feminine grace and yet it made a

unique fashion statement. This

paved the way for the Punjabi salwaar-kurta. It

was a convenient and comfortable wear, well within the

confines of modesty and feminine grace and yet it made a

unique fashion statement.

According to Vandana

Bhandari, the arts of stitching and embroidering have

been known to Indians since pre-historic times, but we

always preferred unstitched garments as they were

considered pure.

That’s why along

with modern attire, women retained the unstitched

garments like the Odhni or the chunari as

an integral part of their couture wear, Vandana Bhandari

adds.

"In the sixties and

seventies, the printed nylon and chiffon sarees which

were crease-free and easy to maintain became the

in-thing."

These two decades also

saw the invasion of the hippy movement. Partying and

dancing was introduced to the Indian culture and replaced

devotional gatherings and classical dances. With parties

came a sudden change in attire.

Designer Pranavi Kapur

says, "The sarong was adopted for party wear.

But contrary to popular impression that it originated in

the Orient, the sarong has traditionally been a

part of the heavy garment worn by Punjabi, Keralite and

Maharashtrian women during weddings and festive

occasions.

Role

of cinema in fashions

Interestingly from

1950s, cinema started playing a big role in the lives of

the younger generation and whatever the popular stars

wore became fashion.

Indian cinema, in turn,

was influenced by Hollywood which brought in the minis

and consequently, the length of the kameez was

shortened.

For long, cinema had portrayed that only

the vamp wore tight trousers and low-necked tops with

exposed mid-riffs. The good women dressed only in sarees

or salwaar-kurtas. For long, cinema had portrayed that only

the vamp wore tight trousers and low-necked tops with

exposed mid-riffs. The good women dressed only in sarees

or salwaar-kurtas.

But soon all that

changed as modern heroines began wearing western outfits.

"Asha Parekh’s skin-tight kurtas and

Mumtaz’s mini shirts, were copied on Indian roads as

well," says Ruby Kashyam.

However, these tights

were short-lived as they were impractical for Indian

women who were traditionally used to loose and

comfortable clothes. Along with the kurta becoming

looser, the sleeves too underwent changes — from

skin tight to bell-shaped to puffs and even sleeveless.

The size of salwaar ponchas changed with every

passing season. There were basically three salwaar styles

— Patiala, Dogri and the Pathani.

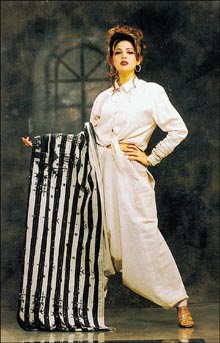

In the ’80s, the dhoti

salwaars and churidars came into vogue.

Prolific use of net, lace, frilled collars, ruffled

sleeves for tops came in as well. But it was still the

decade of the saree for women and staid suits for men.

The dawn of the nineties

changed all that. Communication explosion and the

corresponding rise in the economic status of urban

families turned the fashion scene on its head. Thanks to

the Miss India, Miss Universe, Miss World and other

international pageants, Indian fashions began to get

appreciated worldwide.

With new and innovative

designers graduating from prestigious schools like the

National Institute of Fashion Technology, the scene has

undergone a complete metamorphosis. In fact the wheel has

come full circle in the century. Indian fashions have

swung from the traditional to the western and now seem to

be going back to their roots, the Indian craftsmen have

been re-elevated to their lofty status by leading

designers of the country.

In the coming

millennium, Kumar says, we will be celebrating the legacy

left to us, of the world’s richest repertoire of

handicrafted textiles. In her book she writes that what

is remarkable is that Indian traditional textiles do not

"exist in the rarefied atmosphere of a museum

workshop in an artist’s atelier.... they survive in

the vast weaving, printing, embroidery and dyeing belts

of the country..."

For once, at the turn of

the century, Indian women and men have the freedom to

experiment with whatever is beautiful and affordable.

—

Newsmen Features

|