|

A Satsuma

riddle

By G.S.

Cheema

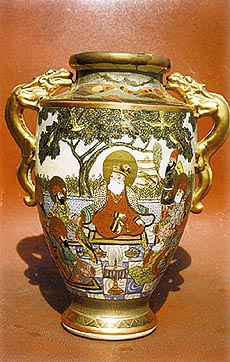

AMONG the various exhibits on

display in the exhibitions put up by the Punjab

Government at Anandpur Sahib and Chandigarh were some

pieces of Japanese ceramics — or to be more precise,

Satsuma faience ware — bearing the pictures of the

ten Gurus. Dated at 1875, or thereabouts, no pieces of

this kind have been noticed before, though, undoubtedly,

others must also have been made. The items are two

identical vases or jars, obviously a pair, and a smaller

pot which may have been intended to be a sugar or tea

caddy. So while the smaller item may have been part of a

tea-set, the vases are purely decorative, and presumably

the client must have ordered a number of them to be given

away as presentation pieces.

Who was

the client? Obviously it had to be a Sikh gentleman of

means. The present owner is one Sardar Atamjit Singh, a

resident of Dehra Dun, and scion of an old sardar family.

But he readily admits that these pieces of Satsuma ware

are not old heirlooms discovered in some store room of an

ancestral haveli which had somehow survived the

vicissitudes of time and fortune. They were picked up by

him from a Bombay antiquarian in the mid sixties, and

according to the dealer he had, in turn, acquired them at

an auction in Hyderabad. There were indeed some Sikh

gentlemen in the service of His Exalted Highness. The

items may have reached the Deccan through them. Maharaja

Ripudaman Singh, the dispossessed ruler of Nabha lived in

exile at Kodaikanaal. Perhaps they may have been his, and

after his death they might have changed hands and reached

Hyderabad. Many of the nobles of the Nizam were extremely

rich, and there were many collectors and men of taste in

this city —the last relic of the Mughal Empire

— besides the redoubtable Salar Jang III. Who knows?

But it is difficult to think of anyone outside the small

circle of the Sikh princes who could have placed an order

for such pieces; so small was the class among the Sikhs

who had the taste and the means — at least circa

1875. Who was

the client? Obviously it had to be a Sikh gentleman of

means. The present owner is one Sardar Atamjit Singh, a

resident of Dehra Dun, and scion of an old sardar family.

But he readily admits that these pieces of Satsuma ware

are not old heirlooms discovered in some store room of an

ancestral haveli which had somehow survived the

vicissitudes of time and fortune. They were picked up by

him from a Bombay antiquarian in the mid sixties, and

according to the dealer he had, in turn, acquired them at

an auction in Hyderabad. There were indeed some Sikh

gentlemen in the service of His Exalted Highness. The

items may have reached the Deccan through them. Maharaja

Ripudaman Singh, the dispossessed ruler of Nabha lived in

exile at Kodaikanaal. Perhaps they may have been his, and

after his death they might have changed hands and reached

Hyderabad. Many of the nobles of the Nizam were extremely

rich, and there were many collectors and men of taste in

this city —the last relic of the Mughal Empire

— besides the redoubtable Salar Jang III. Who knows?

But it is difficult to think of anyone outside the small

circle of the Sikh princes who could have placed an order

for such pieces; so small was the class among the Sikhs

who had the taste and the means — at least circa

1875.

Whereas Chinese

porcelain (and other ceramics, like faience) had been

imported into India and Europe for many centuries, Japan

was a relative newcomer in this field. After the Shimbara

rebellion of Christian converts in 1637, Japan had closed

its ports to foreign ships. Although a tenuous foreign

trade was maintained through the medium of the Dutch who

were allowed to maintain a trading post on a small island

under extremely humiliating conditions, Japan remained

virtually isolated, with its citizens prohibited from

travelling abroad. That is until Commodore Perry with his

armed cruisers entered Tokyo Bay in 1854, and, after a

preliminary shelling, forced the Japanese to open their

ports. This was the USA’s first major foreign

intervention, and, shall we say, an early victory in the

name of free trade?

The history of the

Satsuma potteries is an old one. They take their name

from a district whose capital is Kagoshima on the

southernmost island of Kyushu. It was towards the end of

the 16th century that the feudal prince or daimyo of

Satsuma, returning from a campaign in Korea, brought back

with him a number of Korean potters. One of these

discovered clay deposits of remarkable fineness near

Kagoshima, which became the basis of the prosperity of

the later potteries. One of these very Koreans was also

destined to found a great samurai family and Admiral

Yamamoto, the architect of the triumph of Pearl Harbour,

was one of his descendants. But that is another story.

In the later nineteenth century, Satsuma

ware was in vogue in the European market. It was

characterised by a sombre cream or ivory ground, covered

with a network of fine crackles with enameling and

gilding. The enamels used were red, green blue, purple,

gold, black and yellow. But much of what passed as

Satsuma ware, specially the second grade stuff, was not

really made at Satsuma, but at Kyoto, Tokyo and Yokohama.

In Japan itself this later nineteenth century Satsuma

ware was not too highly valued. It was too closely

attuned to the requirements of the European market. Today

it has lost much of its old reputation, even there. In the later nineteenth century, Satsuma

ware was in vogue in the European market. It was

characterised by a sombre cream or ivory ground, covered

with a network of fine crackles with enameling and

gilding. The enamels used were red, green blue, purple,

gold, black and yellow. But much of what passed as

Satsuma ware, specially the second grade stuff, was not

really made at Satsuma, but at Kyoto, Tokyo and Yokohama.

In Japan itself this later nineteenth century Satsuma

ware was not too highly valued. It was too closely

attuned to the requirements of the European market. Today

it has lost much of its old reputation, even there.

But these pieces are

undoubtedly exceptional. The drawing is strong, and in

spite of the number of figures, each is individualized.

Guru Nanak is easily recognisable and his pose, dress,

and general features are such as are depicted in most

early illustrations. Of course it will be objected that

the colour of his robes is rather unusual for a fakir,

but some allowance must be made for the Satsuma

works’ desire to advertise their mastery of enamel

colours. His expression too is that of a placid and

kindly old man, rather than that of a spiritually exalted

guru. One is reminded of the Laughing Buddha; Sobha

Singh, certainly, would not have approved!

The hawk (or falcon ) on

the wrist of Guru Gobind Singh is also curiously

coloured. But apart from these errors it is a charming

scene. The Guru is seated on a mansard, laid out on a

marble terrace, his back supported by a gao takkiah,

under a pleasant fruit tree, with magical, golden birds

flying about. A nightingale warbles its song from its

golden cage, while Bala stands on the Guru’s left

— his usual place-waning a murchhal, or

peacock feather fan. You have here echoes of ancient

myth, Persian poetry, and the gardens of Firdaus or

Paradise.

The drawing must have

been copied or adapted from some picture furnished by the

client. Copied by a Japanese artist on to the faience

surface, it has undergone subtle changes. We are familiar

with the pictures of the Gurus as drawn and painted by

miniaturists of the Pahari and Sikh schools. We are also

familiar with the paintings of G.S. Sohan Singh and Sobha

Singh, besides the large canvases of historical scenes

painted by Kirpal Singh, Devinder Singh and others. But

here on these Satsuma vases we have a uniquely Japanese

interpretation!

|

![]()