Anand

karaj Amrikan style

By Rebecca Segall

IT was taxi driver Jaswant

Singh’s turn to ride in the white stretch limo.

Thick gold trim hanging

from his hot pink turban framed Jaswant’s face as

the 20-year-old groom strolled into the Sikh temple in

Richmond Hill, Queens, on Thanksgiving weekend for his

arranged marriage to a bride he’d never met.

Throughout New York, in

communities that still practice arranged marriages-Sikhs,

Muslims, Hindus, and Hasidic Jews-young people say they

feel good enough about the ancient practice to continue

the tradition, albeit in a more "American" way.

At Jaswant’s

wedding, his little cousins giggled in awe at the $20 and

$100 bills pasted on his multi-strand pearl necklace. On

the other side of the family divide, wizened old men in

white linen turbans, just arrived from India, joined

hundreds of relatives and friends packed into a small

temple prayer hall, where they sat on the floor in

anticipation of the marriage of their niece, Jasbir Kaur.

"I can’t wait

to see how beautiful she is," said an eight-year-old

girl as she proudly showed her henna-painted hands to a

friend.

"I wonder where she

is," she added.

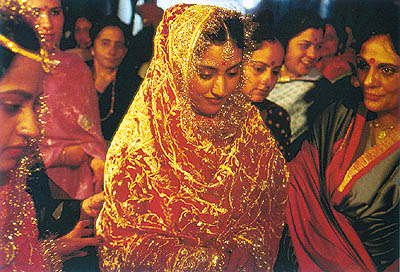

Two hours late,

18-year-old Jasbir finally arrived, shaking and

sniffling. All eyes were fixed on her as she sat in the

middle of a semicircle beside Jaswant. The two bowed,

touched their foreheads to the ground, and agreed to live

together for the rest of their lives. "It’s

normal that she cries," laughed an elderly uncle.

"She is leaving home and her parents for the first

time. She is scared, it’s natural."

"When we Sikhs

marry someone we have barely met," said an earnest

newlywed, "we know that the person we are marrying

has the same background and goals." Love never

lasts, she declared.

After Jaswant doffed his

gold trim, he and Jasbir circled the Sikh holy book, The

Guru Granth Sahib-which is decorated with bright-coloured

swirls-four times. An old man whispered that the book is

considered almost a "god in itself."

Later, in front of the

temple, teenagers clad in Tommy Hilfiger shirts, wearing

gold earrings and medallion necklaces, talk to a reporter

about Sikh tradition.

"I will definitely

marry whom my parents wish," exclaims Dimpy, an

18-year-old who’s been in the U.S. for half his

life. "They know me better than I know myself."

Inesha, a 15-year-old

American-born girl, goes to a Queens school with few

other Sikhs. She hopes to fall in love and choose her own

mate, although one her parents would accept: i.e., a

highly educated Sikh from the Punjab region. "If I

can’t find someone by the time I’m 22 or 23, I

will go to my parents for help," she asserts.

The kids talk about

getting crushes in school, and one girl reveals she

actually dated someone she met online. Sikh teenagers

cyberflirt in Rediff.com’s chat rooms.

Thirteen-year-old AOL

addict and rock band member Amrisha has modern parents.

Her mother, Rupinder, is a social worker (and, at this

temple, a rare career woman). Her father, Hakim, has

short hair (Sikh males’ hair is generally uncut from

birth). However, they met only once in India before they

got married, and speak proudly of the system they take

part in.

The Sikh religion does

not require arranged marriage, Hakim explains. Instead,

the custom is rooted in thousands of years of cultural

practice. In America, it is nearly impossible to arrange

marriages the way it is done back home.

In India, families

routinely do matchmaking, but many young Sikhs have

recently emigrated to the U.S. alone and are living in

small isolated enclaves. Some have been relying on the

Internet to find partners.

Sites such as

SuitableMatch.com and INDOlink.com run

"matrimonial" ads-rather than personals-for the

entire Indian community. The ads are usually placed by

parents. Rather than seeing them as a last resort, many

look to these ads as a starting place.

African American and

ethnic Muslims also find themselves in mini crises over

their cultures’ arranged-marriage strictures, and

have therefore Americanised their system to a degree.

"We don’t live

with the same intensity of community that they do in

Morocco or Egypt," explained Safia, an African

American woman who converted to Islam in the ’70s.

She was speaking in the

women’s prayer room in a small Manhattan mosque as

North African women, covered from head to toe, listened

intently. "We have to consider people who may come

from very far away," she said. "And that poses

the problem of not knowing anything firsthand about the

other family."

Everybody nodded.

"But," unlike

the Middle Eastern women, who said that they could only

marry Arab Muslims, Safia added, "I have no problem

mixing with other ethnic groups, because we are all

Muslim. And Islam preaches no race preferences."

Racism aside, some

ethnic American Muslim youth fear a potential culture

clash.

Nadia, a 20-year-old New

York City-reared college student of Bangladeshi descent,

said that if she doesn’t find someone in her circle

of Muslim friends within a couple of years, her parents

will suggest their ideal candidate: a Bangladesh-born

Muslim.

"But I really hope

not," she added, speaking at the Centre for India

Studies at Stonybrook, Long Island, "because

it’s really hard to relate to each other."

Like Sikhism, Islam

forbids premarital sex, and therefore American-style

dating, according to Sister Raheemah Mohammed of the

Masjid Malcolm Shabazz in Harlem.

So in traditional

Islamic communities, parents assume the responsibility

for finding marriage candidates for their offspring,

carefully examining the upbringing of the potential match

and the reputation of prospective families. But in the

Harlem community, members seek their partners on their

own.

"Arranged marriage

is a custom, not an Islamic precept," explained

Sister Raheemah.

At about age 18, couples

begin going on "Islamically acceptable"

chaperoned dates, followed by a short engagement period

of maybe three months before they are wed, she added.

"Allah knows what’s in our hearts. So

there’s no need for a long engagement if you are

with who you are meant to be with."

Imam Omar Abu-Namous of

Riveside Drive’s Islamic Centre, says that Muslims

of all ethnicities come to him asking for help. He makes

announcements about available individuals at religious

services from time to time. He says that some marriages

have come of it.

It’s Thanksgiving

weekend for the Patels (a family name as widespread in

India as English Smiths or Jewish Cohens). Nearly 3000

members of the prominent Hindu clan have gathered from

all over the U.S. in Atlanta for what 20-year-old Anajali

Patel calls the "meat market." Seven hundred

Patels register as "single."

Three hundred

matrimonies per year are generated by this event, which

is held every year in a different U.S. city, and

follow-up mailings, according to Ravi Patel, chairman of

the Charotar Patidar Samaj Association, which runs it.

The Patels gather for

three days of socials, panels, and vegetarian-friendly

meals in a high-speed attempt at finding new family

members.

Anajali, a Queens-born

Hindu student at SUNY Stonybrook, has a friend who met

her husband at the "market," and knows many

other happily married couples who met there. But she

hopes never to have to go herself.

Unknown to her parents,

Anajali dates-but only other Hindus. "I can’t

relate to the arranged marriage thing because I grew up

here," she says. "I’m used to dating and

to bars." She acknowledges that all the

"successful" marriages in her family have been

arranged. "But I’m too American," she

says. Ultimately, she hopes to fall in love with someone

who will be accepted by her parents, although she may

choose a different path.

Professor S. N. Sridhar,

director of the Centre for India Studies at SUNY

Stonybrook, sees a new marriage model among Hindus: the

child-initiated, parent-arranged marriage.

"It was after my

wife and I decided to get married that our parents ran

background checks on the families, and then planned and

hosted the wedding," Shridar says. "It’s a

common modern Indian compromise." (He says he and

his wife rejected the dowry ritual, which they consider

objectifying, as do many educated Indians.)

According to Sridhar,

Hindu law favours arranged marriage, but allows romantic

unions. Moreover, romantic love is celebrated in Indian

epics and mythology.

The classic drama

Shakuntalam by Kalidasa, the "Shakespeare of

India," is a romantic story about a man and a woman

who meet in the woods and fall in love, Sridhar points

out.

Family values have

overridden the notion of romantic love throughout most of

Indian society, he adds. "In contrast," in the

U.S. "the stress on individuality has encouraged

romantic love.

"But," he

offers, "we can’t forget that although arranged

marriages don’t begin with love, they usually end

with it."

In fact there is a large

body of romantic poetry addressing post-marriage love in

India. In one poem, by K. S. Narasimhaswamy, a recently

wed male meditates:

It was only a month

since I saw her

Love came somehow

unseen.

Need one have heard

or seen or played with the other?...

To be suffused with

the light of love.

The Internet is bringing

evil into the house!" proclaimed a Hasidic father at

a recent religious gathering. "Our kids are flirting

with one another!"

Indeed, one newlywed,

Leivy, explained to the Voice in a twentysomething

Jewish-singles chat room that if it weren’t for AOL,

he never would have "fooled around" before he

met his wife.

Leivy was 23 when he

went out on a date alone for the first time "with a

Lubavitcher girl that nobody knew." They had set up

a date online and once they were out, they realised they

could do whatever they wanted without suffering any

social consequences. "I feel very guilty now, even

though I had a great time," Leivy reflects.

Lubavitch is the only

Hasidic sect that embraces the Net. Its late leader,

Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson, declared that all

technology should be used to spread Hasidism among Jews.

But Rabbi Kasriel

Kastel, program director of the Lubavitch Youth

Organisation, maintains that this banter on the Net is

only a distraction from youngsters’ "studies

and focus."

Kastel, who has just

launched www.mitmazel.com-which includes a program to

help older, modern Jews find marriage partners-asserts

that "Lubavitcher kids don’t need to do

this." At "the right age," they begin

meeting and choosing their future spouses, he explains.

"They don’t need these games."

Yet, at almost any time

in a Jewish chat room, there are likely to be at least a

couple of Lubavitcher youths conversing across gender

lines-and not necessarily only with other members of the

sect. Some of this cybersurfing has led to matrimony.

Moshe, for example, was lonely in England before a friend

recommended that he hook up online. Within a week, he

found a Lubavitcher girl in Los Angeles. They married a

short time later.

Menachem-"Niceboy,"

as he signs himself on AOL-is still seeking a wife in

cyberspace. He grew up in Brooklyn, and is now 24. Time

to marry is running out-Lubavitch males are expected to

be wed by their mid twenties-and Menachem has been having

trouble finding a mate. His rabbi recommended the

Internet.

"Chat rooms are

beginning to change the social order," observes one

26-year-old college-educated Hasid. Boys and girls are

arranging their own dates and marriages. They finally

have a socially safe way to get to know one another.

Traditionally, in Crown

Heights, professional shadchen (matchmakers) organise

meticulous index files containing photos, educational

backgrounds, family information, and medical histories of

marriage-aged prospects.

Parents set up in-house,

supervised dates. If all goes well, a pair ventures out

on their own to a public place like South Street Seaport

or Central Park. Couples date on average two weeks to

three months before an engagement is announced. (In other

Hasidic sects, couples meet only once before they marry.)

"Getting matched up

is becoming ‘in’ now," says Lubavitcher

Pearl Lebovic of the matchmaker centre Likrat Shiduch

(Toward the Match), which serves Jews of all sects.

Lebobic and her husband Rabbi Yeheskel Lebovic have been

connecting young people since 1981.

"Details get in the

way," she emphasises. It’s the demeanour, or

the "feeling they give off," that she clearly

remembers in every person she interviews. Her service is

responsible for approximately three to four engagements

per month.

"The system

isn’t perfect, and it doesn’t work for

everyone," says a recently wed Lubavitch woman,

referring to the exposure of abuse that has emerged in

documentaries about arranged marriages. "But this is

the system we know and trust, the way we couple, and the

way we learn to love.

"So it works for

most of us."

(Downloaded

from the Internet)

|

![]()