|

The moment of

the Khalsa, the moment

of truth

By Darshan

Singh Maini

HISTORY as a discipline has

been interpreted from time to time in many a diverse way,

and continues to be, in some respects, a sum of

imponderables, surmises, imaginative reconstructions etc.

The problematics of historicism in our times have,

therefore, thrown up several subtle philosophical

questions. Without going into such larger issues,

it’s perhaps reasonable to conclude that the drift

in investigation and connotation suggests, among other

things, an engagement of the imagination with the grid of

hidden energies that in a particular period of time

precipitated radical changes in the mindset of a

community or a nation. Even this mode of historiography

runs into difficulties when the history of a major

religion is the subject of research. For the religious

impulse and its passage through time to its final

consummation in scripture and church would seen to follow

a mysterious, inner logic that’s not explicable in

known categories of thought. Thus we are driven back to

ontological arguments positing the existence of God

— and, therefore, of religion. And the enquiry leads

us to understand the dynamics of faith as such. The long

journey of a consecrated community then becomes a series

of insights, epiphanies and contextual coordinates.

Before I take up the

question of Sikhism in the light of the ongoing argument,

it’s necessary to touch upon the idea of the

uniqueness of a particular religion. For in some manner

almost all world religions claim a sui generis character.

The fact is that a faith being ordained by the lord at a

particular moment through the agency of a supreme,

charismatic master is again something that has an

axiomatic base. Its authenticity is beyond our argument.

For religion per se stipulates awe, mystery and fruitful

ambiguity. The sacred and the profane in tandem create,

then, a unified vision. And it’s the story of the

one such visionary faith that concerns us here as we

approach its 300th birth anniversary as an organised,

consecrated religion, complete with name, signatures and

insignia. Leaving aside hagiography except where it helps

light up a particular issue, it’s left to the

imagination of discovery and reverence to put the history

of the Khalsa in perspective.

However, I do not mean

to cover the heroic saga of Sikhism form Guru Nanak to

the Tenth Master stage by stage, for this great story is

well chronicled in scores of volumes. Nor do I wish to

dwell on those moments of ordeals and sacrifices and

martyrdoms that helped anneal the Sikh spirit en route,

and gave the community its greatest periods of pride,

power and glory amidst a host of intractable,

insurmountable problems. Instead, this brief essay is

directed towards those airs and essences which gave the

Sikh Panth its true identity. To be sure, when we leave

the history of the faith out of this account, we do not

mean to say that its genius and character—i.e. its

essences and values—could be studied in isolation.

For essences become the mark of a community through

action and engagement. And what’s history, finally,

but a long story of word, deed and commitment?

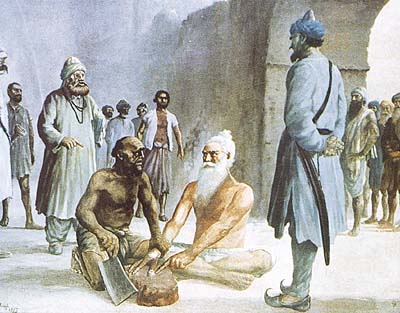

The arrival of a people

sworn to a certain set of moral values and observances

after a tempestuous passage through the deeps of time and

contingency brings us, thus, to the meaning of the moment

when Guru Gobind Singh, in a spectacular ceremony, rich

in symbolism, announced the birth of the Khalsa on the

Baisakhi day 300 years ago. History, I may add, in

general, and the history of religions, in particular, has

many an example to illustrate the Greek concept of Kairos

which Paul Tillich, a leading 20th century thinker, has

briefly discussed in his book The Eternal Now. The word

means in the Greek language, "the right time".

To quote Tillich, "All great changes in history are

accompanied by a strong consciousness of a Kairos at

hand." In the case of Sikhism, we may thus identify

two primal or significant moments —the first when

Guru Nanak broke away from the moribund, sacerdotal

Hinduism of his day to found a new creed of vision and

work, and the second when the wheel of faith came full

circle with the formal baptism of the Khalsa by the Last

Master.

That moment, then, was

the moment of making, of a moment that brought to a

heroic conclusion the vast, untapped energies of a people

given to a life of labour and endeavour. In other words,

all the disparate elements, sects, splinter groups within

the Sikh fold were unified into a Commonwealth of the

Khalsa . At one stroke, all distinctions of caste, birth,

colour and degree were abolished. A sword had flashed in

the sun, and a community rechristened, was invested with

a large humanist dream, given a definitive mandate, and

set on the high road of history. The subsequent events

that shaped the community’s Collective Consciousness

only authenticated the primal vision, which, coming from

Guru Nanak, gathered energies and fresh dimensions

through the successive Gurus, a vision consummated when

the Tenth Master closed the chapter of human succession,

and made the Adi Granth, compiled earlier by Guru Arjan

Dev, the sole authority in matters of doctrines, values,

right conduct etc. It may not be out of place to mention

here that the Sikh holy scripture has no parallel in the

world so far as its Catholicity and supremacy of song are

concerned. It carries not only the bani of the

Gurus, but also the compositions of saints and divines

owing allegiance to different creeds, tongues and

cultures. That’s why Guru Gobind Singh pronounced it

the Sikhs’ guide, mentor and Guru.

It’s important at

this stage to aver that the scriptural finality was not

to be taken as the truth embalmed in letter only. The

word became a divine message, and the vision flesh when

there was a complete harmony between the letter and the

spirit. Thus, at the very outset, Sikhism was so primed

as to frown upon lifeless rigidities and orthodoxies. In

fact, a certain kind of mental resilience, or hospitality

to other thoughts was built in the very fabric of the

bani. A mere worship of the letter produced in the end

one-dimensional, closed communities, whereas Sikhism

embraced new thoughts without jettisoning its heritage of

insights and values. That’s why, in a very special

sense, it remains modern in its outlook. The essentially

egalitarian world-view of the Gurus, and the essentially

democratic character of all Sikh institutions and bodies

set it apart from militant, monolithic religious

communities. To be sure, we have, in the last few

decades, seen the supremacy of the letter over the spirit

in Sikh polity, a grievous departure from the legacy of

accommodations and magnanimities. No wonder, the

bewildered community finds itself fragmented, mired in

controversies on the threshold of the Great Day.

To return, then, to the

theme of this essay, we have to understand the dialectic

of the Sikh dream. And this dialectic is nothing but a

study of those essences which Sikhism has earned

and propagated. This should draw our attention to the sum

of moral values which are in danger of being eclipsed in

the face of to-day’s forces of hedonism, runaway

consumerism and low pragmatism.

On the top of the table

is the value of truth which is the highest virtue in Sikh

ethics. In Guru Nanak’s own words, it’s even

higher than right conduct. For truth is God’s own

attribute, and, therefore, a transcendent, inalienable

value:

Truth is higher than

everything else,

But higher still is the living by truth.

A vigilant and creative

concern is, thus, needed to keep it inviolate, sacred,

and in a state of readiness. Other Sikh virtues include,

among other things, extinction of ego, pity and

compassion, forgiveness and the generosity of heart, a

soulful, vigilant respect for woman, an empathic

understanding of the adversary point of view, courage in

the cause of dharma or righteousness, living by

the sweat of your brow, a watchful regard for the poor

and the lowly.

At the same time, if

despite all one’s efforts to persuade a tyrant who

wilfully and wantonly commits acts of aggression,

there’s no remedy left to put matters right, then

the lifting of the consecrated, sword becomes an

inescapable moral obligation. As Guru Gobind Singh wrote

in Zafarnama or "The Epistle of Victory"

addressed in Persian to the Moghul Emperor, Aurangzeb,

the sword in such circumstances becomes an instrument of

justice and redresser.

When the situation is

past all measures of persuation,

It’s thy rightful duty to lift the sword.

In conclusion, we are

obliged to ponder deeply the condition of the

Khalsa Panth as we stand on the cutting edge of

history. In the same measure we are obliged to suggest a

purposive agenda for the generations ahead. How should we

go about the business of a helpful renaissance without

losing sight of the realities on the ground? Can the

youth, in particular, be weaned away from the vices that

have taken a global colour? These and other related

questions brook no easy answers. All that one may say

with a degree of confidence or certitude is something

that has stood the test of time — the eternally

radical character of Sikhism, the universal, timeless

values incorporated into the Sikh sensibility, and the

structured sense of meeting all assaults of the changing

reality. In sum, history flowing through the Sikh blood

and veins in itself is the shield against the doomsday

tribe of scribes and cynics. It’s possible, the

organised religion may adopt new forms of expression, new

styles or action inconsonance with the Zeitgeist or

"time-spirit", but that, one may add, is the

chief characteristic of all organic and vibrant species

of life. The Yogi Harbhajan Singh phenomenon in

the United States — the conversion to the pristine

aspects of Sikhism of a small section of the American

youth for over three decades or so — itself should

prove the enduring enfranchisement of the creed. A

limited example, but it’s symbolic of the inherent

strengths of the Khalsa.

The need, therefore,to modernise

our outlook, our strategies of revival and

rejuvenation, becomes an urgent imperative. The Sikh diaspora,

in particular,would need new directions, new ways to

remain in step with the reality back home and with the

reality overseas. The moment of the Khalsa ought to be

the moment of truth, and even in the midst of rejoicings,

grand centenary marches and conferences, we may remember

that greatness and glory lie more in meaningful

recoveries and fruitful reorientations than in eyeful

spectacles, or in brave shows of fabulous ceremonies.

|