Guru

Nanak’s system of thought and ethics

By J.S.

Grewal

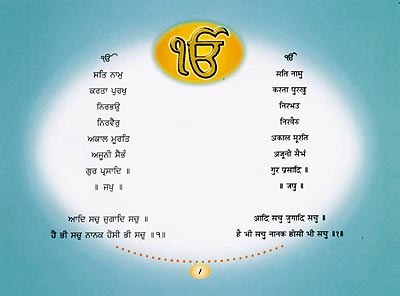

THE whole thought of Guru Nanak

springs from his understanding of the nature of God. His bani

bears witness to his experience of God. He is one. He

is eternal. He is immanent in all things and he is

sustainer of all things. He is the creator of all things.

He is without fear and

without enmity. He is not subject to time. He is beyond

birth and death. He is responsible for his own

manifestation. He is known by the grace of the Guru. God

is both transcendant and immanent at one and the same

time. His ultimate essence is beyond all human categories

of conception but he has also manifested himself in his

creation. He is not an impersonal ultimate reality but a

personal God of grace.

From his absolute

condition He, the Pure One, became manifest; from nirgun

He became sagun.

The dynamic principle

that makes the unmanifest (nirgun) God manifest (sagun)is

the name (nam) which stands equated with God. Once

this is grasped, all epithets used for God begin to

underline his unity. He is Allah and Khuda, He

is Ram and Madho, He is Niranjan and Nirankar. The

use of these epithets does not mean that Guru

Nanak’s conception of God is the same as that of the

Koranor the Puranas. Significantly, Brahma,

Vishnu and Shiva are not supreme deities for Guru Nanak.

They are God’s creatures, millions upon millions.

Their existence is acknowledged but in a way that makes

them totally insignificant. They have no role whatever to

play.

God has revealed Himself

partially in His creation. The universe is the Word (shabad)towards

the Creator spoken by God. Contemplation of the Word

leads who, thus himself becomes the preceptor is the only

true guru (Guru). In fact, He (satguru). ongoing

process of The dynamic universe, or the universe in its

creation, preservation and destruction, is the expression

of God’s will. The entire universe works in

accordance with His order comprehends (hukam) which

everything in the physical and the moral world. Not even

a leaf falls without His hukam.

Divine self-expression

through the name, the word and the divine order is

symbolic of the grace of a compassionate God who Himself

shows the way as the true guru.

As the Creator of

humankind, God is the Father and Mother of all human

beings. They are all equal in his eyes. This ideal of

equality springs directly from Guru Nanak’s

conception of God as the Creator. The supreme objective

of life, as conceived by Guru Nanak, was meant for all,

irrespective of one’s caste, creed, country or sex.

This universality was a

logical corollary of his conception of equality. The

egalitarian ideal involved rejection of the caste system

based on the principle of inequality. It also involved

rejection of the distinctions of class and gender. The

ethical principles enunciated by Guru Nanak were

uniformally applicable to all.

In other words, there

was one single dharma for all human beings. Guru

Nanak gave concrete expression to this ideal of equality

in congregational worship (Satsang) and community

meal (langar). Both these were open to all men and

women.

A unique aspect of Guru

Nanak’s ideal of equality was the principle of the

freedom of human conscience. Men and women were free to

profess and cherish beliefs. External compulsion had no

justification. It is well known that Guru Nanak denounced

injustice and oppression, especially the oppression of

common people by the members of the ruling class.

What is not generally

known is the principle on which Guru Nanak denounced the

contemporary ‘Muslim’ rulers. They

discriminated between their subjects on the basis of

differences in their religious beliefs and practices. By

doing this they infringed the principle of freedom of the

conscience.

Significantly, this was

the principle which Guru Tegh Bahadur demonstrated with a

deliberate sacrifice of his life. Whereas the Mughal

emperor Aurangzeb took his stand on

‘compulsion’, Guru Tegh Bahadur stood up for

freedom, not only of the Sikhs and Hindus but of all

religious communities of the world. The earliest

reference to his martyrdom refers to him as the

‘protector’ of the world (jagg di chadar).

Guru Nanak’s

attitude towards the contemporary systems of religious

belief and practice can be appreciated in this context.

It is generally aknowledged that Guru Nanak did not

ascribe any spiritual merit to external or ritualistic

observance of any kind. It is often asserted or assumed,

however, that Guru Nanak was ‘influenced’ by

the Sufis, the Jogis and the Vaishnava bhaktas.

Of these three, the Jogis find the most

frequent mention in the compositions of Guru Nanak.

References to them reveal his familiarity with their

beliefs and practices.

However, Guru Nanak has

several serious objections to the Jogis. Their

assumption that one could attain to the highest spiritual

status by self-effort was an index of their haumai. It

denies the grace of an omnipotent God. The Jogis’

objective of exercising supernatural powers was futile.

It had no ethical import. The Jogis’

insistence on renunciation actually meant the

renunciation of social responsibility which was essential

to the ethics of Guru Nanak.

The Sufis too are

mentioned many a time in the compositions of Guru Nanak,

but not equally frequently. They are certainly better

than the orthodox ulema, the mullahs and

the qazis, who are a part of the unjust

establishment and deal out externalities.

The religion (din)

of the Sufis (auliya) rightly emphasises the

importance of inner faith. However, the Sufis too have

their shortcomings. They receive state patronage in the

form of revenue-free grants from the rulers who are

unjust and oppressive and who discriminate between their

subjects on the basis of religious differences.

The Sufi Sheikhs are

also presumptuous enough to think that their salvation is

assured and they authorise their disciples to lead others

to salvation. They are likened to a rat which is too fat

to enter the hole and yet attaches a basket to its tail.

The Vaishnav bhakti

or the worship of Rama and Krishna, does not figure

prominently in the verses of Guru Nanak. The

personification of gods and goddesses in dance and drama

are denounced by Guru Nanak as something that compromises

the great majesty of the unincarnate God. Thus, we find,

that Guru Nanak’s attitude towards the major forms

of religious belief and practice of his times was

informed by his conception of God.

The early western

writers looked upon Guru Nanak’s faith as syncretic,

that is, a mixture of ideas borrowed from Islam and the

Hindu tradition. Subsequently, scholars started looking

for ‘influences’ on Guru Nanak. In this

context, the Sufis, the Jogisand the Vaishnava bhaktas

assumed great relevance and importance. A further

step was taken by looking at the Sant tradition as a

‘synthesis’ of Nath, Bhakti and Sufi

influences, and placing Guru Nanak within the Santtradition.

The basic flaw with all

these approaches is that they leave out the personality

of Guru Nanak. To get to the heart of the matter, it is

essential to think in terms of Guru Nanak’s

historical situation, his experience, and his creative

response.

His understanding of the

nature of God and his experience of God provide the

essential clue to his entire system of thought and ethics

— a system that is autonomous and a self-contained

whole. It calls for a comparative study, that is, a study

of both similarities and differences with the other

religious system of the world.

|