|

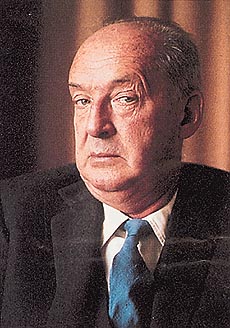

The joyous

stylist

Although

quite prolific as a poet and a short story writer,

Vladimir Nabokov’s reputation rests almost solely on

the novel, a form whose potentialities he kept on

exploring all along with much enthusiasm. Irreverent and

provocative, this man who detested Freud mischievously

parodied traditional literary forms to produce works

complex in structure yet thoroughly entertaining,

comments Vikramdeep Johal.

IN Andre Gide’s The

Counterfeiters, (1926), the protagonist Edouard, a

writer, thinks that "a good novelist can never be

made out of a good naturalist." These words contain

more than a grain of truth, as one considers the problems

inherent in the task of fusing literature and life, words

and things, imagination and experience. One novelist of

the post-war era who accomplished it with aplomb was the

Russian-American writer Vladimir Nabokov. Through his

dazzling prose, he not only showed us our own world in

all its richness and diversity, but also created

alternative ones that never failed to mesmerise and

beguile the reader.

Although quite prolific as a poet

and a short story writer, his reputation rests almost

solely on the novel, a form whose potentialities he kept

on exploring all along with much enthusiasm. If the first

half of this century belongs to Joyce, Proust and Mann,

the second one has been dominated by Grass, Marquez and

Nabokov. Irreverent and provocative,

this-man-who-detested-Freud mischievously parodied

traditional literary forms to produce works complex in

structure yet thoroughly entertaining. Although quite prolific as a poet

and a short story writer, his reputation rests almost

solely on the novel, a form whose potentialities he kept

on exploring all along with much enthusiasm. If the first

half of this century belongs to Joyce, Proust and Mann,

the second one has been dominated by Grass, Marquez and

Nabokov. Irreverent and provocative,

this-man-who-detested-Freud mischievously parodied

traditional literary forms to produce works complex in

structure yet thoroughly entertaining.

This cosmopolitan

artist’s corporeal journey, which took him to many

places on both sides of the Atlantic, began on April 23,

1899, in St. Petersburg. Born into a family of White

Russain aristocrats, he learned English and French at a

very early age, becoming in his own words, "a

perfectly normal trilingual child." Two volumes of

his verse in Russian got published while he was still in

his teens. Then came the Russain revolution, which forced

his family to flee West. He continued his studies at

Trinity College, Cambridge, where he earned a B.A. in

Slavic and Romance languages in 1922.

The years he spent in

Berlin (1922-37) and Paris (1937-40) constituted the

first mature phase of his writing career. Disturbed by

the rise of dictators like Hitler and Stalin and the fast

vanishing dream of democracy, he stressed the

significance of creative freedom in two Kafkasque works, Invitation

to a Beheading and Bend Sinister, both set in

totalitarian regimes and narrating the

intellectual’s attempts to protect his personal

integrity against oppressive forces. Also, he drew on his

rich memories of Tsarist Russia in his early writings.

However, as World War II reared its ugly head, the sense

of dislocation caused in him by a nomadic life

intensified.

"At a certain turn

of my existence in the late 1930s," he recalled,

"I had to decide which country to choose for a

permanent backdrop." That country turned out to be

United States, as he left Europe with his wife and son to

take up an academic post at Stanford University. In

America, he became highly respected both as a teacher of

languages and literature and for the other passion of his

life, lepidoptery (butterfly collecting).

The Real Life of

Sebastian Knight (1941) was his first novel in

English. The story of mediocre writer preparing the

biography of his dead brother, apparently a great writer,

it probed the art of fiction and dealt with the

Pirandellian theme of subjectivity of truth, which was to

recur in his later works.

After producing a

memoir, Speak, Memory, largely an account of his

childhood and adolescence in Russia, he dropped in the

year 1955 a bombshell by the name of Lolita. The

hell-raising story of Humbert Humbert, a middle-aged

European scholar who falls madly in love with a

twelve-year-old American girl was a unique combination of

erotic wit, lyricism and satiric social commentary.

American publishers loved it — but none of them

dared to send it to the printers. He then sent the

manuscript to France where it appeared first, drawing a

mixed bag of responses. On one hand it was called

"immoral" and "pornographic", and, on

the other hand, "original" and

"remarkable." Its American edition came in 1958

and became a bestseller. Four decades on, the work still

enjoys worldwide popularity, even in India (though for

the wrong reasons).

Lolita is

definitely not a pornographic novel. Its sensual, poetic

prose precludes any comparison with the X-rated trash

flooding the market. Consider, for instance,

Humbert’s lovely description of this nymphet as she

positions herself for a tennis serve: "My Lolita had

a way of raising her bent left knee at the ample and

springy start of the service cycle when there would

develop and hang in the sun for a second a vital web of

balance between toed feet, pristine armpit, burnished arm

and far back-flung racket, as she smiled up with gleaming

teeth at the small globe suspended so high in the zenith

of the powerful and graceful cosmos she had created for

the express purpose of falling upon it with a clean

resounding crack of her golden whip".

The novel is also

valuable for its sharp and spicy observation of American

society and culture (Lolita is to America of the

late forties and early fifties what The Great Gatsby

is to the twenties). With effortless ease, it swings

between the beautiful and the beastly, the sublime and

the ridiculous. With scientific precision —

incidentally, he was research fellow in entomology in

Harvard — Nabokov exposed the rottenness underneath

the kitschy exterior of a crassly commercialized nation.

Pale Fire, (1962)

is one of those books that has to be read in order to be

believed. Here Nabokov mocks all those pompous literary

scholars — he must have met a lot of them in

American universities — who are always eager to

flaunt their intellectual biceps and erudite triceps. The

novel consists of a 999-line poem in heroic couplets,

composed by a recently deceased American poet; in

addition, there is an extensive and farfetched commentary

by his university-colleague and neighbour, an eccentric

scholar who may or may not be the exiled king of a

Russia-like country named Zembla.

Political intrigue gets

mixed with pedantry, the autobiographical with the

biographical, the memorised with the imagined, as the

reader follows the bizarre notes of the royal

commentator. To give just one example of his genius, upon

reading the lines. It was a year of Tempests:

Hurricane/Lolita swept from Florida to Maine.

Our scholar writes:

Major hurricanes are given feminine names in America. The

gender is suggested not so much by the sex of furies and

harridans as by a general professional application. Thus

any machine is a she to its fond user, any fire (even a

"pale" one!) is she to the fireman... Why our

poet chose to give his 1958 hurricane a little-used

Spanish name (sometimes given to parrots) instead of

Linda or Lois, is not clear."

Many of the insane

critic’s claims and explanations are pretty shady

and, apart from enjoying them, one often doubts his

honesty (this idea of the unreliable narrator was used to

good effect by Salman Rushdie in Midnight’s

Children). For its superbly controlled unorthodox

structure, its wild humour and its linguistic-literary

acrobatics, Pale Fire is arguably Nabokov’s

tour de force.

The writer has been

compared to Joyce for inventiveness of wordplay, to

Lawrence Sterne for brilliant use of the first-person

narrative and to Proust for wonderful evocation of mood

and setting. About his writing style, he said:

"While I keep everything on the very brink of

parody, there must be, on the other hand, an abyss of

seriousness. And I must make my way along this narrow

ridge between my truth and the caricature of it." A

chess enthusiast, he loved playing games with the

readers, presenting them with alternative realities like

pieces of a jigsaw puzzle which only when put together

could give a comprehensive picture.

Nabokov vehemently

rejected the idea of fiction as a vehicle for social,

political and moral messages. He expected a novel to

provide him with nothing more than aesthetic pleasure,

"a sense of being somehow, somewhere, connected with

other states of being where art (curiousity, tenderness,

kindness, ecstasy) is the norm," as he put it.

Neither was he impressed by the literature of ideas nor

by psychoanalysis. He hated being labelled as a

symbolist, an allegorist or a surrealist and repeatedly

expressed his contempt for what he called "Freudian

voodooism" and "generalizations devised by

literary mythists and sociologists." For him

creative satisfaction was the strongest motivation for

writing a novel. Not surprisingly, his aesthetic stance

alienated quite a few critics and scholars.

After teaching for a

decade at Cornell university — which provided the

background for Pnin, a satirical portrait of a bumbling

Russain emigre professor — he returned to Europe

with his wife in 1959 in order to pursue full-time

writing. Until his death in 1977, he lived in a posh

hotel in Montreaux, Switzerland, preparing English

versions of his Russian novels and writing new ones. The

theme of forbidden erotic pleasures resurfaced in Ada

(1969), his last major work in which he parodied the

fictional family chronicle, a sub-genre made popular by

19th century Russian novelists. The memoir of a

nonagenarian narrator, recalling his long love affair

with his sister, it is a complex novel with sci-fi

leanings, packed with esoteric data and literary

allusions.

Eccentric emigres,

naughty nymphets, loony lovers — his wonderful

characters seem to be blessed with the gift of

immortality. For his vast erudition (which he both

paraded and parodied), his wild imagination and satiric

humour, his extraordinary powers of description and

intelligent experimentation with form and content, it

would be difficult to forget Nabokov his works will

continue to amuse, amaze, shock and perplex readers.

|