|

A heroic

conception

More

or less, all the caves of Badami have a similar plan: the

mukhamandapa, the mahamandapa

and the garbhagriha with

a lingam. But the most

distinguishing features of all the caves are the

life-sized panels, some of which are of outstanding

merit, maintains Arun Gaur

FROM Hampi, it takes me eight

hours to reach Badami. It was a tough time trying to make

enquiries about buses and their schedules. They normally

talked in irritated Kannada to me and the script on the

buses imperiously told me nothing. The oft-repeated

"w" letters made fun of me. Somehow, changing a

bus on the way and hoping that I was on the right track,

I reached Badami.

It was getting increasingly dark outside

and through the bus-window, I could feel the shapes of

the passing rocks as we lurched forward. Over them, clear

star constellations were hanging silently. It was getting increasingly dark outside

and through the bus-window, I could feel the shapes of

the passing rocks as we lurched forward. Over them, clear

star constellations were hanging silently.

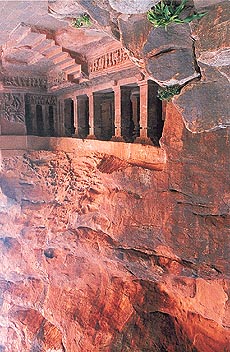

In the morning, climbing

the flanks of the sandstones, a part of the Kaladgi

series, I sensed the shifted romance of the daylight. On

my immediate right on the southern massif were the caves

with their mysterious images. Down below was the big tank

turned deep shining green probably due to the plantation

growth in water. Near its bank the town-houses were

huddled together uncannily like thousands of closely

parked trucks trying to intrude into the U-shaped fault

determinedly occupied by the tank. Scores of washerwomen,

standing in knee-deep green water with their saress

tucked high up, were busy in their scrubbings and

lashings. Merciless beauties!

Their sarees —

pink, blue, green, — looked beautiful in the early

morning light. On the other end of the tank was the

Bhutanath temple. It became glorious in the late diffused

pallied light, the two blue-eyed German lasses told me.

If we looked straight into the air, right across on the

equivalent height was the desert of red rocks and

scrub-bushes, with no tree visible. At places the

structural temples looked as reddish as the rocks on

which they stood.

The Aihole inscription

of Pulaksein-II tells us that the

"tiger-haired" king was a night of death for

the Nalas, the Mauryas, and the Kadambas (Nala Maurya

Kadambakal-ratri). Not only did the Chalukyas under the

leadership of Pulaksein-I, Kirtivarman-I, Mangalesha, and

Pulaksein-II halted the march of Harshvardhan on the

northern banks of Godavari, but also kept, at least for

sometime, under severe restraint the ever-ebullient

Pallavas, and stretched their suzerainty far and wide in

the south. Thus, it became almost imperative for them to

create something which should be of outstanding artistic

and religious merit; reminding the generations of what

they were and incidentally and unintentionally, of what

became of them later. The four caves of Badami turned out

to be, partly, an intentional sequel to such a line of

thought.

They are held to be the

product of the sixth century. The foundation inscription

of the cave-III of Manglesha dates that cave at 578 A.D.

If we gradually climb up from the cave-I to the last

cave-IV, the chronology of excavation should roughly

follow the same pattern, though many scholars prefer a

different time-sequence of excavation.

Lack of

sufficient number of epigraphic sources, pin-pointing the

date and other contextual information, creates

uncertainty. Unlike the Pallavas, who enjoyed displaying

their newly-developed Tamil script, the Chalukyas were

somewhat deficient in this respect. Of course, we can

also assign the relative periods under which a particular

cave must have been excavated by noticing the cult-trends

of iconography and trying to match it with the personal

propensities of the different kings. Thus, while the

first two caves have the Shaiva predominance, the third

cave where Manglesha is said to have installed the image

of Vishnu is patently Vaishnava. The fourth cave is

Jaina. Neither the Chalukyas nor the Pallavas were

hostile to Jainism; probably because of the similarities

in their structural canon and even because of the

sensitive inter-assimilation that took place between

their respective sets of icons. Jaina, Vaishanava and

Shaiva monuments may stand together. With the Buddhistic

structures, the story may take a different, even a nasty

turn. Lack of

sufficient number of epigraphic sources, pin-pointing the

date and other contextual information, creates

uncertainty. Unlike the Pallavas, who enjoyed displaying

their newly-developed Tamil script, the Chalukyas were

somewhat deficient in this respect. Of course, we can

also assign the relative periods under which a particular

cave must have been excavated by noticing the cult-trends

of iconography and trying to match it with the personal

propensities of the different kings. Thus, while the

first two caves have the Shaiva predominance, the third

cave where Manglesha is said to have installed the image

of Vishnu is patently Vaishnava. The fourth cave is

Jaina. Neither the Chalukyas nor the Pallavas were

hostile to Jainism; probably because of the similarities

in their structural canon and even because of the

sensitive inter-assimilation that took place between

their respective sets of icons. Jaina, Vaishanava and

Shaiva monuments may stand together. With the Buddhistic

structures, the story may take a different, even a nasty

turn.

More or less, all the

caves have a similar plan: the mukhamandapa, the mahamandapa

and the garbhagriha with a lingam or a

provision of an image. But the most distinguishing

feature of all the caves are more than life-sized panels,

some of which are of outstanding merit.

Siva, busy in his tandava

nritya, on the wall projected out of the first cave

with his 64 kinds of hand-gestures, is not as enigmatic

as the vinadhara vrishabhantika Siva in the mukhamandapa.

The problem is how to unite man and woman in one whole.

And they are united through the concordant notes of

veena, when the fingers of both Siva and Uma play

synchronistically on the same instrument. Observing this

experiment, the emaciated figure of the Bhringi stands in

a corner in an ambiguous stance. Everything in him seems

to be sinking inward, only his eyes pop out. He salutes

the divine pair with folded hands but he cannot conceal

his amusement, a grin flits across his mouth.

The opposite harihara

panel expresses the same problem not in terms of the male

and the female worlds, but in terms of the union between

the dark-unconscious world of Siva incorporating the jataka

hair, the moon, the skull, the cobras and the bright

conscious world of Vishnu. But in this case, in contrast

to the musical union of man and woman, the two gods

remain sharply bifurcated.

The trivikrama

and the varaha of the cave-II are repeated in the

cave-III much more imposingly. It is in the cave-III that

many of the conflicting tendencies — thematic,

structural or iconographic, seem to be settling down in

the trivikrama, the narasimha, the harihara,

the varaha and the vaikunthanatha panels.

Not only are they designed to overawe the onlooker with

the sheer sense of weighty divinities, almost brutal in

carrying out their merciless predetermined designs, but

also their being grouped together at such a lofty level

enhances the feeling of terror in the believer and the

non-believer alike.

The trivikrama

that is outside the mukhamandapa, is the most

striking figure. A monumental reserve of energy is held

in pause by the fully outstretched straight leg of the

deity. The straight lines crisscrossing each other lend a

sense of pitiless determinacy. The vertical lines of

head, sword blade firmly held to charge at a

moment’s call and the parallel horizontal left arm

and leg flung to their extremity where the demon-mask

dangles hopelessly — all of these seem to make a

mockery of the human-effort springing out of the

so-called devilish aspirations. The reflected light from

the fore-noon sun suffuses the divine face and the mukuta

of Vishnu that glow. In contrast to this gigantic play of

the force beyond human control, in the dramatic display

of miniaturised figures, God is present in the form of an

archetypal trickster figure asking Bali for his boon of

destruction. Namuchi clings to Vishnu’s left leg in

the left corner desperately trying to stall the design of

divinity but would be soon contemptuously flung away.

Just in the

neighbourhood of this panel, inside the mukhamandapa,

there is a menacing leonine stare of the Narasimha. Above

his hands seem to be hovering two ayuddha-devatas

— the chakra and the shankha. But the

standing Bhu supported on the palm of the varaha

is just not as relaxed as many of the over enthusiastic

commentators would make us believe. Otherwise enigmatic,

it does not carry the sense of an action or a pause.

Everywhere, the brutal energy — lion, boar, cobra

— seems to be at the disposal of God.

The cave-IV of the

Jainas, though not as grand as the Brahmanical ones,

offers a different version of iconic-art and includes the

Gommata with legs entwined with snakes.

Though these are the

giant panels that are obviously the most outstanding

accomplishments in cave-art, a different kind of delight

awaits the onlooker when he beholds the mithuna

couples and the other related figures formed within

brackets. The contexts that many of these figures present

give an insight into the social, ethical and

philosophical background of the times: A lady arranging

her hair in mirror, while her baton-wielding attendant is

ready to quell any ogling; a lover supporting the limpid

inebriated beloved, a woman about to bathe in the river,

a male offering a bloom to a coy mistress. While the

giant divinities restrain us with their overpowering

sense of awe and fate, these are the delicate gestures in

the secular scenes that let us breathe the essence of

human freedom.

|