B.N. Goswamy

The universe is made of stories, not of atoms

— Muriel Rukeyser

I am sure some of us remember from our childhood stories in which trees spoke: sharing a secret about a hidden treasure with a traveller resting under its shade, addressing spirits hiding in its leaves to go and perform an assigned task, and so on. Vivid images sprang to mind when one heard these, not necessarily agreeable but certainly giving wings to imagination. One heard the stories in the night, I recall: the next morning every tree looked different.

At that time, one did not know, of course, that there is an ancestry to these tales. They were not native to India alone: trees that spoke were in every, or nearly every, culture. One had to travel in the mind to the Islamic world, for instance, to land upon riches. There were legends there about the Speaking Tree which bore human fruit and was to be found in mythical lands or on an island by the name of Waq Waq. The great Firdausi speaks of it in the Shahnama; so does Nizami in the Iskandarnama, one of the five long poems in his celebrated work, the Khamsa. In both these works, Alexander — Sikandar as he is known in Islamic texts — figures not only as a conqueror but also as a philosopher king, full of questions, always curious to learn. The story of him standing at the foot of a tree which talks has held fascination for writers and painters for a long, long time.

Firdausi writes of Alexander reaching, in the course of his travels, the end of the world where he encounters a tree with two trunks. Male heads sprout from one trunk and speak during the day in a voice that strikes terror, and female heads from the other trunk talk sweetly at night. The male heads warn Alexander that he has already received his share of blessings, and the female heads urge him not to give in to greed: but both predict the same thing that his last days are near. “Death will come soon: you will die in a strange land, with strangers standing by”. This, as one knows, is exactly what happened. Alexander died in Babylon, far from his home.

The fascination with the legend has persisted over centuries even as it changes in different lands, and in different hands. Liberties are taken with it, departures made. There are versions in the Thai language; variations of it in Arabic literature. In painting, sometimes, one sees Alexander on horseback close to the foot of the tree, straining to listen; at others, the great conqueror is nowhere to be seen and only the tree appears, with human figures suspended from its branches. The tree is sometimes a symbol of prophecy; in other works, it represents our inability to comprehend the mysteries that surround us.

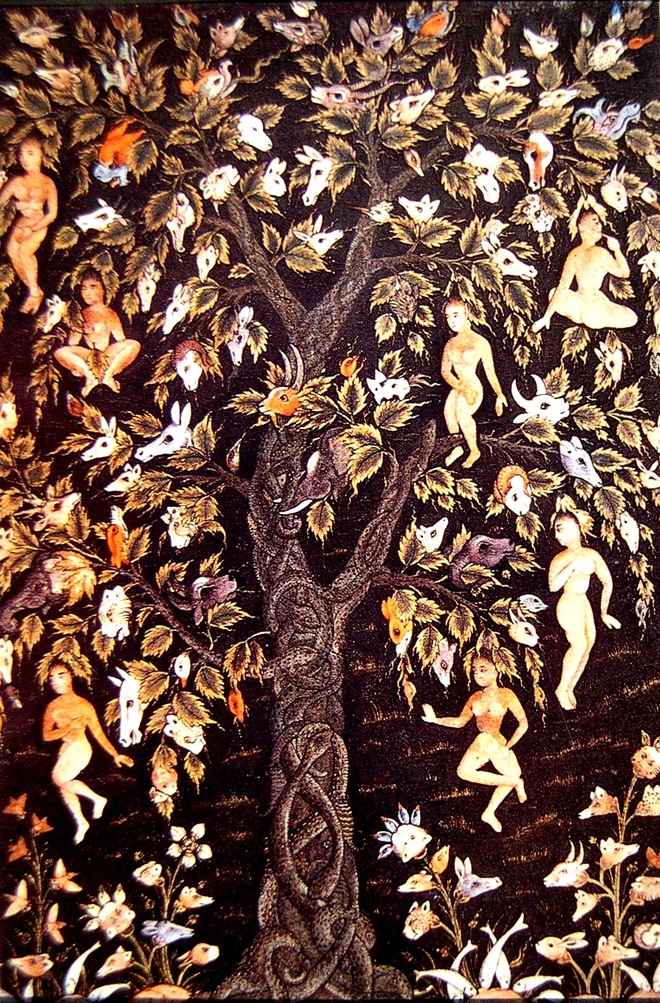

The painter of the mystifying, somewhat eerie, work that is reproduced here creates a surreal world in which, to begin with, nothing is quite that it appears to be. The tree, teeming with figures of humans and beasts — one can see heads of leopards and horses, deer and elephants, rams and foxes, peeping through the leaves — is made up of a trunk that is nothing but snakes, intertwined and slithering, even as they turn into branches. What appear like bushes in blossom, close to the foot of the tree, bear heads of other animals rather than flowers; and resting their heads on a rock close by are fish that seem to have come from nowhere and positioned themselves thus. If one looks at the rocks that lie about one sees in them hidden shapes: a rabbit here, a frog there.

I am tempted to move to another culture, and cite short passages from a poem by the nearly contemporary American poet, Muriel Rukeyser. In it. she speaks about a Speaking Tree.

The trunk of the speaking tree looking like a tree trunk

Until you look again

There people and animals

Are ripening on the branches, the broad leaves

Are leaves; pale horses, sharp fine foxes

Blossom; the red rabbit falls

Ready and running

She continues:

The trunk coils, turns,

Snakes, fishes. Now the ripe people fall and run…

Flames that stand

Where reeds are creatures and the foam is flame.

Close to the end of the poem come these lines:

This is the speaking tree,

It calls you name. It tells us what we mean.

It is unlikely that Muriel Rukeyser had seen the very painting that appears here: perhaps another version swung into her view somehow and touched her off. The present work must undoubtedly have challenged the painter of it — we do not know who it was — almost beyond straining point. It is generally regarded as coming from Golconda in the Deccan, although a Mughal ancestry cannot be ruled out. To recall: the Qutb Shahi Sultanate of Golconda was founded by Turkmen princes, and during the early years of their reign, Turkmen artists seem to have settled in the region as well. It is entirely possible that it was they who laid the ground for the style that came later to flourish in that soil.

PS:- I was tempted once to count the number of creatures that reside in or hang from this Speaking Tree. I counted eighty-two.

Unlock Exclusive Insights with The Tribune Premium

Take your experience further with Premium access.

Thought-provoking Opinions, Expert Analysis, In-depth Insights and other Member Only Benefits

Already a Member? Sign In Now