Rana Siddiqui Zaman

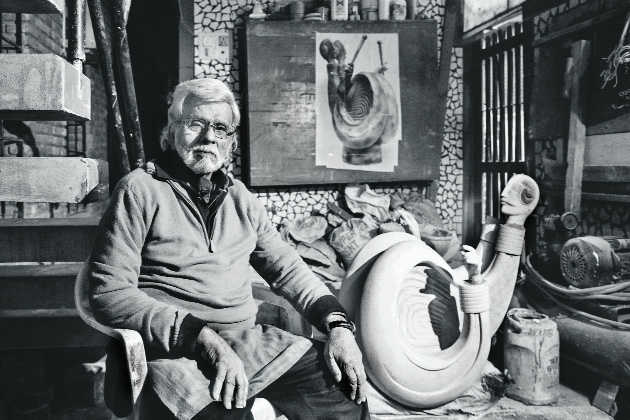

At 90, the legendary artist, sculptor and poet Satish Gujral is no longer able to supervise and monitor the way a mini-retrospective of his entire career is mounted on the walls of the immensely spacious Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, New Delhi, which concluded yesterday.

Of late, he has been in and out of hospital because of knee and heart ailments. Even though largely restricted to home, Gujral loses none of his vigour, strength of voice, his ever-present smile, and humour. His memory is still his best aide. His inability to hear (from the age of eight due to an accident) is overshadowed by his capability of painting a picture through words. At home, he is reclining on a couch, his legs covered with a sheet. He has just celebrated his 90th birthday and The Gujral Foundation run by his son Mohit and daughter-in-law Feroze decided to gift him a mini-retrospective of his show.

His wife Kiran Gujral (a painter and ceramist) has been an immense support to him. Her lips he reads to answer most questions. She is temporarily restricted to the wheelchair for health reasons. But her beauty retains, her face belies her age, and the smile covers her pain.

Extending a hug, she says in Punjabi — pointing at him — “Tumhare liye taiyyar kar ke bithaya hai”. Gujral reads her lips and passes a mischievous smile.

“So, you haven’t seen your own show yet?” “I will go”, he says, “It’s a surprise gift for me. Have they mounted Lala Lajpat Rai’s portrait I made?” Certainly, and a lot more, I say.

“Punjab swears by Lalaji”, he begins the story of the portrait.

“For Parliament, his portrait was to be painted. My father Avtar Narain (a political activist) was very close to Lalaji. He told him that he would get it made by me (Satish) for free. He didn’t ask me. I had just returned from Mexico, in 1952. Those days, Barada Ukil was the Chairman of the All-India Fine Arts and Crafts Society (AIFACS) — central Delhi’s premier art gallery and research centre. He asked me, ‘How will you make his portrait? Whose style will you use? Use Amrita Sher-Gil’s style.’

“I asked, ‘Why not Satish Gujral’s style?’ At that time, Charles Fabri (famous art critic) entered. He asked Ukil, ‘Till the time Amrita was alive, you kept criticising her, now you are praising her style’.”

But I made the portrait according to my style. It went to the Art Committee of Parliament, of which Ukil was a member. He rejected my portrait. Those days I didn’t have enough space to store such a big artwork, so I kept it in the storehouse of Modern School, Barakhamba Road. Charles Fabri heard about it and wrote an article against it in The Statesman. Jawaharlal Nehru read it and called me. He asked me to show him the portrait. We took it to Teen Murti Bhavan. After seeing it, he asked Ukil why he had rejected it. Ukil said, ‘Because of the moustaches. It doesn’t look like Lalaji’s.’ Nehru retorted, ‘Do you admire Lalaji only because of his moustaches?’ He then dismissed the committee on the grounds of agenda-based selections. Next day, I was supervising one wing of the Parliamentary Art Committee.”

The portrait still hangs on the walls of Central Hall of Parliament.

With a mischievous smile, Gujral adds, “The next day, Nehru called me for dinner and said in a lighter vein, ‘You have depicted Lalaji as a lion in your portrait, he didn’t look like a lion.’”

The show has several works procured from the Punjab and Chandigarh Museum. Gujral turns emotional on the sheer name of Punjab. He recalls Partition days that affected his works and are considered among his most poignant. It has countless, faceless women, wailing and brooding. The earthy and dark hues lend an infectious sadness to his oil-on-canvas.

He recalls, “When Partition happened, I was at a refugee camp in Lahore. I was one of the members of the Punjab Committee. We had gone to Karachi to take oath that we will not go to Pakistan. When the mob attacked our house, Krishan Kant (Vice-President of India) and Lalaji left their property in the name of the People of the Servants’ Society and Lala Lajpat Rai Bhavan became a refugee shelter.

“On August 30 — I have a graphic memory of that day — my father came back from Karachi. By then, Nehru Bhavan became the biggest refugee camp. Nehru had not taken oath till then. He asked my father if there was any hope, my father said no. Nehru said, ‘You have killed me by saying no’.

We then took him across the city. Seeing a big box, Nehru jumped to speak to the people but the mob got furious. They wanted to shoot him. They were shouting, ‘Now you have come to sympathise?’ His faced turned white. My father took him to Lala Lajpat Rai Bhavan. He just asked, ‘Which side will Lahore go?’ He said, ‘I have spoken to Liaquat Ali, it seems it will go to Pakistan.’” After some rigorous works on Partition, he never repainted the anguish. He reasons it with a couplet from Faiz Ahmad Faiz: “Na raha junoon-e-rukh-e-wafa, ye rasan ye daar karoge kya/Jinhein jurm-e-ishq pe naaz tha, wo gunah-gaar chaley gaye.”

(There is no longing for loyalty, so why carry on? Those who cherished committing the crime of love, have left forever).

Show time

Titled a “A Brush with Life” (extracted from his biography edited by Khushwant Singh), the show spans his nearly 70 years of career. Curated by Pramod KG, the show has 70 original works of art juxtaposed with rare archival photographs of people like Ocatavio Paz, poet Faiz, Amrita Sher-Gil and his parents, who influenced his life and works.

Besides interesting texts extracted from Gujral’s biography edited by Khushwant Singh, the mammoth flex light boxes also showcase Inder Kumar Gujral, former Prime Minister and his elder brother, who removed Satish Gujral’s name from all prospective lists of art committees of the government to maintain the dignity of the PM’s office. Renowned photographer and critic, Richard Bartholomew, famous Mexican painter husband-wife duo Frida Kahlo and Diego Riveria, also find mention. Diego, the text says, took Gujral to collect Frida’s ashes after her death and insisted him to help him finish a mural in her memory.

The most interesting text is about Nehru’s conversation with Charles Edouard Corbusier, who was reportedly Nehru’s choice for planning and building Chandigarh. Gujral reveals in the text from the letter Nehru wrote to him, “Last night Mr Corbusier had dinner with me. In my answer to a question what does he think the style of architecture of Chandigarh city would be, he said, ‘You wear trousers, drive autos and adopted the Westminster’s style of architecture. There is no Indian style.’ ‘This man scares me, keep an eye on him.’"

While the first section of the exhibition is laden with his portraits of Nehru, Lala Lajpat Rai, Krishan Kant, his girlfriend Nancy in Mexico, and oil paintings on abducted, rescued women during Partition, the other showcases iconography from Christian to Hindu mythology. The other rooms of IGNCA have different phases of his life: the happy phase in which works have human beings and plants, birds pulsating with rhythm, moments when he got back his hearing capacity after 67 years. That phase has ample musical instruments, the sounds which the artist tried to familiarise himself with.

The most poignant part of the show is a section which has a black and white photograph of Gujral and his wife Kiran, besides a few paintings, with subtle shades Gujral is not known for. The huge picture taken by Madan Mahata accompanies a poignant, beautiful text by the painter: “Kiran held my hand as I walked the valley of silence. Kiran had taken the load of my isolation on her shoulders, relieving me of my alienation, gave me a sense of my being a part of the society and stimulated my work, producing my best...” The paintings, rarely shown, were made by the artist when Kiran was temporarily ill.

The sculpture section comprises huge lyrical bulls, in bronze and stone, his architectural installations way ahead of times. For instance, an installation based on his feeling when Russians first left Sputnik in the space, and so on. His burnt wood sculptures, way ahead of the times, still have no parallel.

A show worth watching, it, however, left something to be desired. For those who know the artist’s works, a glimpse at his marvellous skill and style, is almost a repeat view. The dim lights made it difficult to read and view textures. It was a chance, however, to educate the youth about the story behind each work, and its meaning. A short note to this effect was required. Lack of texts often leave such inspiring shows more of an elitist affair, excluding new learners.

Unlock Exclusive Insights with The Tribune Premium

Take your experience further with Premium access.

Thought-provoking Opinions, Expert Analysis, In-depth Insights and other Member Only Benefits

Already a Member? Sign In Now