Jaspal Singh

Ninder Ghugianvi, a prolific Punjabi writer, has led a very interesting life. Son of a small village-shopkeeper, he dropped out of school for his infatuation with Punjabi folk singing, a field in which he could not make a mark. To eke out a living, he became a lawyer’s munshi (clerk) in the district court at Faridkot, soon to be appointed as a court orderly by an amiable judge who took pity on the poor boy slogging as a munshi on paltry wages. As a court menial, he would function as a crier and after court hours, he was supposed to reach the judge’s residence, to work as an errand boy-cum-cook till late in the evening. Only the wages were better than that of a munshi! Every day, he would write all his experiences in a diary. And that is how he eventually became a well-known writer, transforming his diary entries into highly readable books like Goda Ardali (Goda, the Orderly) and Mai San Jajj Da Ardali (I was a Judge’s Orderly).

Another field in which Ninder excelled is that of writing the biographies of celebrated Punjabi folk singers like Lal Chand Yamla Jatt, Surinder Kaur, Karnail Singh Paras, Puran Shahkoti, Gurcharan Virk, Amarjit Gurdaspuri, Hans Raj Hans and so on. By now, he has written or edited nearly 40 books and about half of them are on Punjabi folk singing. He has also written a number of travelogues that give details about his visits to various countries of the world where he was honoured by important personalities like the Prime Minister of Canada Jean Chretien (2001) and British Labour MP (now shadow Chancellor) John McDonnell.

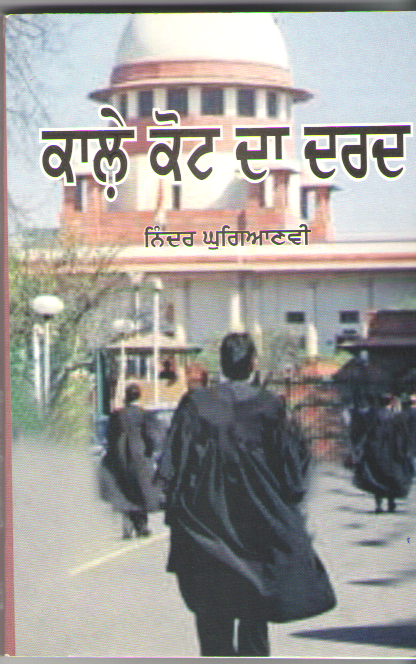

Ninder’s latest book Kale Kot da Dard (The Affliction of the Black Coat) to be dealt with here is about the lives of a dozen-odd judges with whom Ninder worked as an orderly. Perhaps for the first time, judges’ lifestyle, limitations and problems have been intimately portrayed in Punjabi literature. On the basis of his first-hand experience, Ninder says that many judges lead the life of glorified bonded labourers, toiling from morning to evening without any socio-cultural sublimation. A judge is supposed to be a recluse, snapping all social and kinship ties. The junior judges are always under the eagle eye of the district judge besides that of the prying lawyers. Even in their commodious residences, the judges are ‘prisoners’. A judge doesn’t get to attend parent-teacher meetings of his child in the school nor can he accompany a sick relative to the hospital. Even the social functions of relatives are usually avoided and proxies are used to make do. This kind of isolation of the judges is supposed to be in the interest of justice.

The author believes that now a part of the judiciary is getting politicised with the penetration of politicians’ progeny into the system. The phenomenon of ‘uncle judge’ in the High Court is all too well-known. But how to deal with such things in the lower courts is a mute question. Earlier, most of the judges in the subordinate judiciary were from the middle or lower middle class. But now those from well-off families are also entering the profession, thus changing the social profile of judiciary. A few from the lower classes are usually complex ridden.

Ninder points out a number of misdemeanours and wrong-doings perpetrated by the judges, thus tarnishing the image of the judicial system. The retired life of most of the subordinate judges is dull, dry and drab. Some of them met him even in foreign countries and they weep at their plight. The characters presented here, despite their seclusion and seeming callousness, form a mosaic of various human traits that get unfolded in various existential situations. The protagonists like Mukhtiar Singh, Durga Dutt, Sardul Singh, Ram Narain, an irritable madam judge Jaswant Dhillon, Ram Gopal, Dalip Singh, Harbir and so on (names changed) are ‘objects’ and not individuals. Some corrupt judges are also ruthlessly exposed.

The last write-up in this book is a long pathetic story of a young judge Harbir with a failed pre-marital love, followed by a miserably failed marriage with an upper-class lady judge. The boy gets addicted to heavy drinking and eventually damages his liver. He weeps on the shoulders of his mother cursing the day he became a judge.

Some years back Mittar Sen Meet, now a retired district attorney, wrote a few novels like Tapteesh (Investigation) and Katahra (Witness Box) about the shoddy investigation and prosecution system in the country. But Ninder’s books are a pointed though sympathetic peep at the lives of subordinate judges. Many retired senior judges of higher courts have commented on his writings in laudatory terms. The court orderly would one day become a renowned writer is not less than a miracle. Ninder’s publishers Chetna Parkashan, Ludhiana ought to be more careful in editing the scripts though.

Unlock Exclusive Insights with The Tribune Premium

Take your experience further with Premium access.

Thought-provoking Opinions, Expert Analysis, In-depth Insights and other Member Only Benefits

Already a Member? Sign In Now