Rumina Sethi

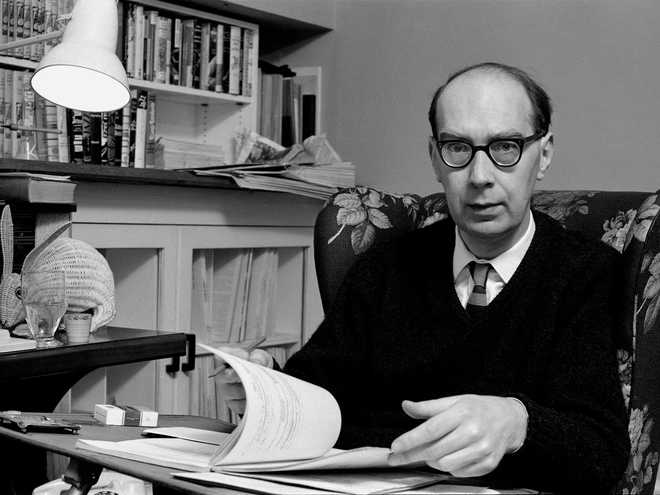

Philip Larkin believed in poetic simplicity unlike T S Eliot, who assumed that all contemporary poetry “must be difficult”. For Larkin, like Tolstoy, poetry was the expression of sincerity, a compulsion of the inner need to express one’s feelings. It is this sincerity that impels the artist to express what he truly feels, “a sincerity as unselfconscious as it is absolute.” Unique lucidity of phrase is its hallmark. Reverting to the virtues of the 1930s’ poetry of Auden, Larkin’s writings never abandoned the “objective, outward-looking, political, materialist, unpretentious.” But conflicting depictions of Larkin, the man and the poet, leave a rather confused picture of one of the most admired poets of the last century.

Though the high quality of Larkin’s writing was apparent from his early verse in The North Ship (1945), his distinctive talent came to be seen in his collection of poems The Less Deceived (1956). The Whitsun Weddings in 1964 and High Windows in 1974 show his growing concern for a landscape that has lost touch with its history, its mythology and its rituals. It is here that he becomes a spokesman for his generation and its angst for a land that has emptied itself of its past, a condition that becomes his objective correlative, a bleak outside world that resonates with an inner turmoil and a pervasive sense of wanting to be left alone. We see the world-weary observer impressed by nothing and depressed by everything in the poem Going:

There is an evening coming in

Among the fields, one never seen before

That lights no lamps

***

Where has the tree gone, that locked

Earth to the sky? What is under my hands

That I cannot feel?

Haunted throughout by death, life for him was a “deprivation.” “I think writing about unhappiness is probably the source of my popularity, if I have any,” he expressed in an interview, “After all most people are unhappy, don’t you think?” In the poem Dockery and Son (1964), he writes: “Life is first boredom, then fear.” Decency, dejection and failure, and the worry about getting old became his staple obsessions serving as raw material for his very moving poems. “The ultimate aim of a poet,” he argued, “should be to touch our hearts by showing his own.”

On the publication of Selected Letters, edited by Anthony Thwaite in 1992, and in Andrew Motion’s biography the following year, the true Larkin was finally revealed to the world. It was news to the public that he had more than six women as lovers, and sometimes more than one simultaneously. It was equally shocking that he held very right-wing views on the question of race and class and admired Thatcherism.

However, this shocking picture of him now stands revised by James Booth, his colleague at Hull for almost two decades, who examines the poet and the man, showing how those associated with him found him inherently warm and caring. What Thwaite had missed out in his book of Larkin’s letters was the huge collection of correspondence with Larkin’s mother Eva, who remained his responsibility until she died. For 30 years, he cared for her, often writing to her about their past. He did get restless and burdened by her illness and long life and looked forward to freedom, but that came only two years before his own death. However, it was Eva who was the inspiration behind some of his finest poems like Love Song in Age and The Building.

His attitude to women is complex. Larkin, the misogynist, always lingers under the man who exhibits affection and concern for the women he loved. The egoist in him remained till the end. He safeguarded his space, never gave into committing himself to marriage even though he had a fifteen years courtship with Monica. “I do feel terrible about our being forty and unmarried,” he writes, but he would never relent and went on with his endless pursuit of women. He always held out in his poetry that he was not much of a lover and that he hesitated where women were concerned. This could well be one of his clever strategies of winning them over with a rather charming reticence. It was the women in his life who became his victims. In his poem, Love, he wrote: “How can you be satisfied / Putting someone else first / So that you come off worst? / My life is for me / As well ignore gravity.” Booth tries to defend Larkin by presenting a more positive picture of him as a man with Left leanings and against racism.

The account becomes more and more one-sided as we progress through the biography and Larkin continues to remain an enigma. Even if Larkin was racist and sexist in his private life, it is perhaps best to let it be as long as he appears sincere in his poetry. For, it is the dance that matters, not the dancer.

Unlock Exclusive Insights with The Tribune Premium

Take your experience further with Premium access.

Thought-provoking Opinions, Expert Analysis, In-depth Insights and other Member Only Benefits

Already a Member? Sign In Now