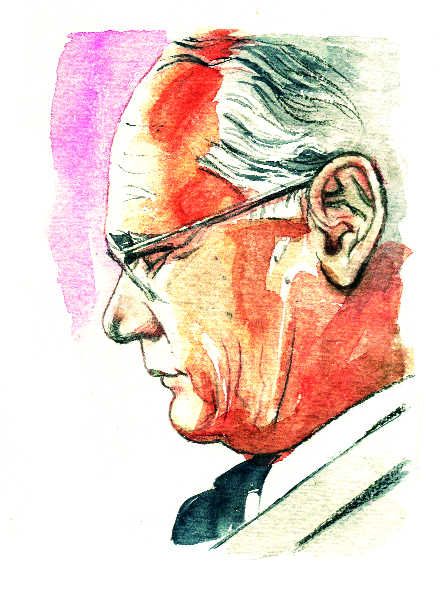

Brajesh Bhatia

It was in August 1947 that I heard the name of Mr MS Randhawa for the first time. I was studying in the first year at DAV College, Dehradun, which declared a week’s holiday to celebrate Independence, so I came down to Delhi, where my elder sister and brother were staying.

They were living in a rented accommodation on Abdul Ahad Street (later changed to Tilak Street), just behind the Imperial Talkies in Chuna Mandi, Paharganj. Four to five-storeyed houses on both sides of the street were inhabited mostly on one side by the Hindu and the other side by Muslim families. A large number of guests had come down to take shelter from the riot-torn places in these buildings.

I accompanied my brother to watch the proceedings on the Rajpath, then known as Kingsway, and even came across Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and could shake hands. There was no security, like nowadays, for the Prime Minister. He had the habit of getting down from the vehicle and meeting the common people.

And then a few days later, Delhi witnessed Hindu-Muslim riots with Chuna Mandi-Paharganj the main venue. The night’s peace used to be disturbed by the chants of “Allah-hu-Akbar” and “Har Har Mahadev”. The inhabitants of houses on both sides had collected stones and bricks on the rooftops and at the slightest aggravation the pelting would start.

This situation continued, if I remember correctly, for two days. The Delhi Police could not control the riots. Then it was announced on the radio that one Mr Randhawa, a young ICS officer, has been appointed the Deputy Commissioner and was given full powers to maintain law and order in Delhi. The first thing he did was to withdraw the entire Delhi Police force (where the lower ranks were mostly filled by Muslims as Hindus in those days would not join the police force as constables) and confined the personnel to their barracks. He requested the Army to loan him a Gorkha Regiment. He first imposed 24-hour curfew and gave the soldiers orders to shoot at sight any miscreant. Calm descended within two days and the curfew was relaxed.

Mr Randhawa was a man who could take drastic decisions at the spur of the moment. Eight years later, in November 1955, I landed my first government job as technical assistant in the Publications Division of the Indian Council of Agricultural Research at the newly built Krishi Bhavan. My boss was Mr MG Kamat, Editor (Magazines).

At ICAR, I came to know that Mr Randhawa was head of this organisation as the vice-president, the Minister of Food and Agriculture being the president. He was academically a scientist – MSc, PhD, DSc, FNI in botany from the University of Edinburgh; by profession an administrator and on top of it an authority on Kangra valley paintings and his books on these paintings, published by the noted UK publisher, Allen and Unwin, perhaps priced at $100 per copy in those days.

My habit of reaching office before the boss landed me in trouble some months later. I had just reached my desk when the telephone rang. It was Mr Kamat asking me to go to Mr Randhawa’s office as he needed someone who could understand Punjabi. I could not speak Punjabi as I was from Uttar Pradesh, but since I had been living in Delhi for so many years, I could understand the language to some extent.

Mr Randhawa was standing in the centre of his huge office quite enraged and blabbered in choicest Punjabi language that the Deputy Secretary (Administration) could not follow his command. The official had come to tell him that the selection committee for the day was waiting for him. Mr Randhawa, after seeing the file, asked him to call all the candidates together. The secretary kept on telling him to come to the meeting room instead.

Mr Randhawa told me to assemble all the candidates then and there. I asked all 23 to form a line against the wall in the corridor. He asked those candidates to step forward who had the desired as well as additional qualifications. Seven moved forward and then came the next command — any one currently working in ICAR should come forward. Only one candidate, Mr SKS Dhariwal, moved forward and the result was announced — “selected”.

I was later told that Mr Randhawa had given a discourse on this episode in the next officers’ meeting. The post was Assistant Exhibition Officer, Class II gazetted, and had to be recruited through the Union Public Service Commission. However, in urgent cases, the department concerned could make temporary ad hoc appointments, but regular recruitment could only be done by the UPSC within six months. Hence, why waste time of four to five senior officers to interview 23 candidates and if someone was working in ICAR and was qualified, why not give him a chance and let the work continue.

That was Mr Randhawa. Decisive as ever.

Unlock Exclusive Insights with The Tribune Premium

Take your experience further with Premium access.

Thought-provoking Opinions, Expert Analysis, In-depth Insights and other Member Only Benefits

Already a Member? Sign In Now