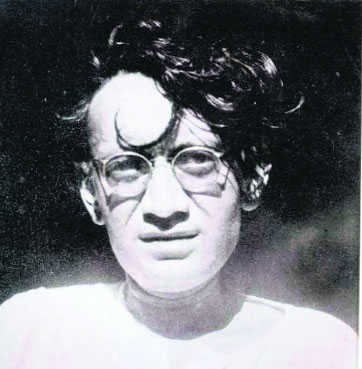

Last Sunday, I landed up by chance at a play performed in Delhi. Ek Mulaqat Manto Se was an endearing solo performance by NSD graduate Ashwath Bhatt, who also happened to be the director. It was simple, sharp, and moving. I reached home to search out my copies of Manto, and reread portions to remember that no one wrote of the “bitter fruit” of Partition as Saadat Hasan did. As had happened decades ago when I first read Manto, I am again being haunted by his works and his life.

He died in 1955 at the age of 43, broke, often drunk, traumatised by the Partition that he saw as a great tragedy and often presented as a farce. Utterly trapped and disillusioned in Pakistan, he longed for India, more specifically Bombay. Some of his friends believe that he began to die the day he set foot in Pakistan in 1948. But imagine if Manto had returned to live in Mumbai, not Bombay, and lived on to a ripe old age. He would at the very least have turned out dark satire about dug-up cricket pitches, burnt books, vandalised exhibitions, riots and bomb blasts. Beyond politics and identities, his short stories and portraits about the underclass of Bombay and the world of cinema make him a bigger writer than just the best chronicler of the Partition.

I believe that Pakistan certainly did not deserve Manto, who was repeatedly tried for obscenity in that country. But neither does India, in the narrow sense where nationhood prevails over humanity. I do wonder what a Shiv Sena would have done with a living Manto. Burnt his books and accused him of hurting patriotic and/or religious sentiment? Manto’s madness and irreverence, genius and pathos make him the eternal resident of the Toba Tek Singh of his own imagination. May that restless soul get some peace and may he forever torment us from his grave.

This month, India and Pakistan began another round of laboured meetings that signal an attempt to normalise relations. On the face of it we are attempting to look like civilised neighbours, but let’s face it, the story of the two nations has gone horribly wrong. We must wonder too if there is real political will behind this in the current regime in India, or will electoral rhetoric and calculations again derail this fragile attempt? No doubt the influential nations of the world such as the US would be strongly encouraging us to talk.

Yet, understand too how callously the great powers have shaped histories. Read the biting but prophetic words of Manto in the fourth of the nine Letters to Uncle Sam written between 1951 and 1954. He wrote this in 1954:

“Dear Uncle, my admiration and respect for you are going up at about the same rate as your decision to grant military aid to Pakistan. Regardless of India and the fuss it is making, you must sign a military pact with Pakistan because you are seriously concerned about the stability of the world’s largest Islamic state since our mullah is the best antidote to Russian communism. Once military aid starts flowing, the people you should arm first are these mullahs. They would also need American-made rosaries and prayer mats, not to forget small stones that they can use to soak up the afterdrops following a call of nature. Cut-throat razors and scissors should be top of the list as well as American hair colour lotion. That should keep these fellows happy and in business. I think the only purpose of military aid is to arm these mullahs. I am your Pakistani nephew and know your moves. Everyone can now become a smart ass, thanks to your style of playing politics.”

Sixty years ago, Manto intuitively sensed the beginning of an awful history where mullahs would be armed to the teeth. This week, on December 16, we also noted the first anniversary of the attack on a school in Peshawar where seven members of the Tehrik-i-Taliban killed 132 schoolchildren between the ages of eight and 18.

One of the best contemporary Pakistani writers must surely be Mohammad Hanif, whose A Case of Exploding Mangoes is an eternal bestseller. These are the powerful lines Hanif wrote after the Peshawar massacre: “By the time you read this despatch, the funeral processions would have been over. Small-sized coffins for the primary section children; normal size for high school.”

He wrote too of the prayers that would be offered for the souls of the departed:

“I think these prayers are unnecessary. What possible sin could children studying for their matric exam or in middle school or in primary classes have committed that you would need prayers for forgiveness? …Hence, my ardent request to Pakistan’s political and military leadership, not to worry overmuch about the afterlife of these children. When they do raise their hands in prayer tomorrow, they should do so for their own deliverance and, in doing so, look at their own hands carefully, to see if they are not stained with blood.”

Unlock Exclusive Insights with The Tribune Premium

Take your experience further with Premium access.

Thought-provoking Opinions, Expert Analysis, In-depth Insights and other Member Only Benefits

Already a Member? Sign In Now