Aveek Sen

Journalist working on cyber security and geopolitics of India’s neighbourhood

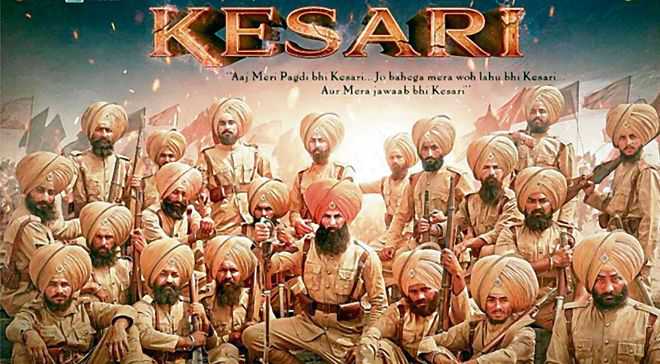

AKSHAY Kumar’s movie Kesari is about the Battle of Saragarhi, fought between Afghan tribesmen and the 36th Sikhs regiment of the British Indian Army in 1897. While the battle showcased Sikh valour, it served British imperial interests and should not have been glorified.

The movie starts off with the narration that following the decline and fall of the Sikh empire, which had extended till Afghan lands, the British took control of the three forts of Lockhart, Gulistan and Saragarhi. From time to time, mullahs (Islamic clerics) would incite Afghan tribesmen to wage jihad.

Saragarhi is situated in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa was known as the North West Frontier Province during the Raj. The area is considered to be occupied territory, and till date Afghanistan does not accept the borders the British drew through Afghan and Pashtun land. The region of the Gandhara civilisation had been predominantly inhabited by the Pashtuns not only during the few centuries after the creation of the modern Afghan state by Ahmad Shah Durrani, but also for thousands of years. The Durand Line border drawn through the Afghan heartland is a colonial British creation and Indians should not be sharing the blame for it. Only its colonial masters are to blame for what a colonial army did. The movie has a scene in which Havildar Ishar Singh (Akshay Kumar) laments that they are a ‘slave army’ of the British.

Though the film doesn’t outrightly vilify the ‘other’(Afghans), one would still identify with the ‘us’ (the Sikh regiment) due to the style of the narration. There is token secularism as Sikh soldiers help rebuild a mosque of the local Afghans and the Afridi tribal sardar (head) declares that the pag (turban) of the Sikhs won’t be desecrated. During the fighting, Ishar Singh lies half-dead on the ground and a mullah tries to desecrate his turban. Ishar Singh stabs him in the throat and then tells the invading contingent that they could kill him but shouldn’t desecrate his holy turban. The Afridi tribal sardar then promises him that they won’t defile his turban. In a later scene, the Orakzai tribal sardar tells the Afridi sardar that there isn’t enough time to attack the other two forts but he won’t return just like that. The Afridi sardar tells him that he may do as he pleases but they shouldn’t desecrate the turban of any Sikh. The tribesmen then proceed to burn down sections of the fort and pillage it.

But are the Afghan tribesmen shown as honourable only as a masquerade? In an early scene, there is a depiction of a tribal jirga (panchayat) where a mullah sentences a woman to death by beheading for running away from the house of her husband, to whom she was forcibly married. Ishar Singh intervenes and saves her. Here the ‘us’ versus ‘them’ characterisation is clear. This scene was unnecessary, if not to project the Afghan tribesmen as savages.

It is not unlikely that such practices were prevalent then because these exist even now. But there is also the modern way of life among the Pashtuns, a large number of whom are Left-leaning. The major party in the Pashtun belt of Pakistan, the Awami National Party (ANP), is a Left-leaning progressive party. The Afghan politicians, too, espouse the cause of women’s rights.

Former Ambassador Rajiv Dogra, who has written a book on the Durand Line and British occupation of Afghan lands, says that let us not confuse a battle with the war. A movie on a specific battle will give the impression that the battle is greater than the war. The valour of the Sikh soldiers of the colonial British army is unquestionable, but it has to be seen in the larger context. The Afghan tribesmen were reacting to the British occupying their lands by forcing Afghan king Abdur Rahman Khan to sign the Durand Line agreement. Moreover, Sikhs and Pashtuns have a history of antagonism. The Sikh empire’s writ didn’t go beyond Peshawar when parts of the Afghan territory were under Sikh rule. The British feared the Pashtun and used the antagonism the Sikhs had for them. This took the form of heroism in this battle. The antagonism carried on till Partition when the Pashtuns and Sikhs were at each other’s throats. A movie can’t span centuries and delve into philosophical issues, but this is the larger context.

Human rights activist and advocate Tariq Afghan from Upper Dir, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, questioned why only the ills of Afghan society are shown in such movies. There could be a movie on Khushal Khan Khattak, who fought against Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, says Tariq. Khattak was a warrior, poet, writer, politician, tribal chief and a great military leader of that time. Why not glorify him as he was a strong liberal voice during Aurangzeb’s reign? Aurangzeb imprisoned him in the Fort of Ranthambore. Why not a movie on Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan (Frontier Gandhi), who was a close aide of Gandhi and fought for the independence of the subcontinent. In Pakistan, people call us Indian agents because we are the followers of Frontier Gandhi, says Tariq. “Many books have been written by Indian authors on Ghaffar Khan, but Bollywood has ignored him and his struggle. This is injustice with Pashtuns who supported the Congress before Independence.”

Indian soft power is projected across the world by Bollywood, which is immensely popular both in Afghanistan and the Pashtun belt of Pakistan. One wonders why a movie like Kesari has been made. Most people — whether in India, Pakistan or Afghanistan — have a better sense of history through popular culture rather than through books. As such, the film only serves to pin the blame for British occupation of Afghan lands on Indians.

Unlock Exclusive Insights with The Tribune Premium

Take your experience further with Premium access.

Thought-provoking Opinions, Expert Analysis, In-depth Insights and other Member Only Benefits

Already a Member? Sign In Now