Avijit Pathak

Professor of sociology at JNU, New Delhi

Capitalism has drowned the most heavenly ecstasies of religious

fervour, of chivalrous enthusiasm, of philistine sentimentalism, in the icy water of egotistical calculation. — Karl Marx

That the gifts of the infinite are strewn in the dust wakens my song in wonder. — Rabindranath Tagore

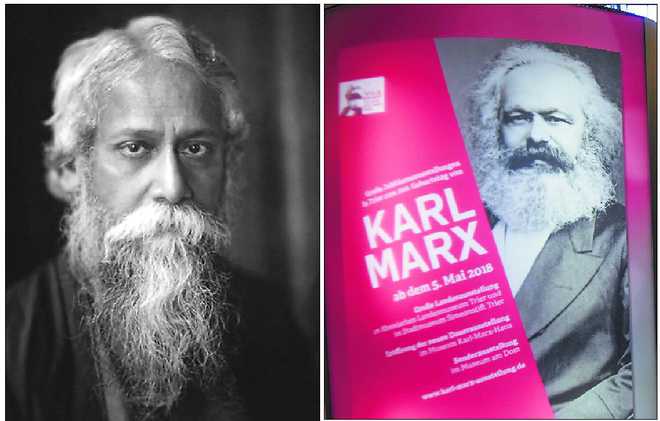

Even though it is election time, and the aggression of instrumental politics is felt everywhere, it is also the time to invoke Karl Marx and Rabindranath Tagore. Marx was born on May 5, 1818, and Tagore on May 7, 1861. In other words, even amid the harsh reality of electoral politics, vote bank, and all sorts of Machiavellian calculation based on caste/religion, I feel like conversing with a poet and a revolutionary. Possibly, in their ‘utopias’ we can find something that can help us to realise that life has a deeper meaning, and politics can also be imagined as an emancipatory quest for a just world.

As a wanderer, I feel that there was something in Marx that took him beyond all sorts of reductionism and scientism. Essentially, his secular religiosity manifested itself in his quest for redemption from fragmentation, exploitation and alienation. Communism, he wrote, is a ‘genuine resolution of the conflict between man and man, between objectification and self-confirmation, between freedom and necessity, between the individual and the species.’ And his critique of capitalism has a deep ethical/spiritual element. Man’s alienation — the way most of us are deprived of unfolding our creative potential because of forced labour — caused pain to him. And eventually, because of ‘commodity fetishism’, we seem to have lost our humanness in relationships; we are transformed into soulless, measurable commodities.

Marx saw conflict in the movement of history; he saw how one’s ‘class’ — one’s location in the production process — tends to shape one’s worldview. Yet, it would be wrong to say that he was celebrating violence, and his ‘materialism’ was devoid of ‘idealism’. In fact, the new society he imagined, as he reflected so profoundly in the ‘manuscripts’ of 1844, would celebrate love — its ecstasy and life-affirming character. Yes, there was a spirit of romanticism and idealism even in his ‘materialism’. Marx read Shakespeare and Balzac; in his words there were tears.

Today, in the age of the triumphant neo-liberal capitalism, all ideals and noble aspirations seem to have disappeared. We normalise violence because it is the language of social Darwinism — the doctrine of the survival of the fittest; we indulge in ceaseless consumption causing severe ecological crisis, and giving birth to a ‘risk society’; and in the name of ‘meritocracy’ and ‘success’ we become increasingly narcissistic and indifferent to social justice, equality and the ethics of care. For a second, let us contemplate on Marx. Like Buddha and Jesus, was he also trying to activate our conscience?

If there is poetry in Marx’s philosophy, Tagore’s poetry has the power to inspire us to strive for a new world. In our times when religion has been reduced to a sword of hatred, a ‘poet’s religion’ — enchanted by the Upanishadic sublime prayers, a quest for building the rhythmic bridge between the phenomenal and the transcendental, or the finite and the infinite, and a constant reflection on the ‘surplus’ of man (something beyond mere pragmatic utility, say, the striving for the illumination of the infinite blue sky, not merely the obsession with the 1,500 sq-ft apartment) — emerges as a breath of fresh air. It purifies. It emancipates.

No wonder, a spirit of universalism guided him. Even at the peak moment of the nationalist movement, he retained this spirit. And, despite his positive and life-affirming engagement with Gandhi, and his reverence for the Mahatma, he could not support the Non-cooperation movement in the 1920s. Tagore was striving for a kind of freedom that is rooted in love — the love that breaks hierarchies, divisions and limiting boundaries. In the ‘poet’s school’, the abundance of nature emerged as the finest tutor; the aesthetics of the ordinary sought to transform the experience of learning into a celebration. Not the power of the disembodied intellect, but the art of relatedness became the objective of education. For Tagore, the power of love was also a kind of resistance against all sorts of hyper-masculine domination. Nandini in Red Oleanders or Anandamayee in Gora, or Ela in Four Chapters indicated this possibility.

Well, he was not anti-modern. Yet, he could see the discontents of a civilisation based on material greed and nationalist pride. ‘The spectre of this new barbarity’ haunted him. Yes, he could see the danger implicit in the doctrine of hyper-masculine militant nationalism.

Yes, what we regard as the ‘real’ world is an anti-thesis of Marx’s revolutionary spirit and Tagore’s poetic universalism. Here is a world — our contemporary India — that seems to have fallen in love with a narcissistic/authoritarian personality; it has allowed all sorts of limiting identities to constrain our possibilities; it loves the ‘spectacle’ in a media-induced world, and entertains a new form of illusion; and it has allowed the market to invade every sphere of life.

This ‘pragmatism’ is killing us —physically, ethically and spiritually. When should we be aware, manage some time to unlearn what techno-managers and narcissistic politicians have taught us, and learn to walk with Gitanjali in one hand, and Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 in another?

Unlock Exclusive Insights with The Tribune Premium

Take your experience further with Premium access.

Thought-provoking Opinions, Expert Analysis, In-depth Insights and other Member Only Benefits

Already a Member? Sign In Now