Mahesh Rangarajan

Professor of History & Environmental Studies, Ashoka University

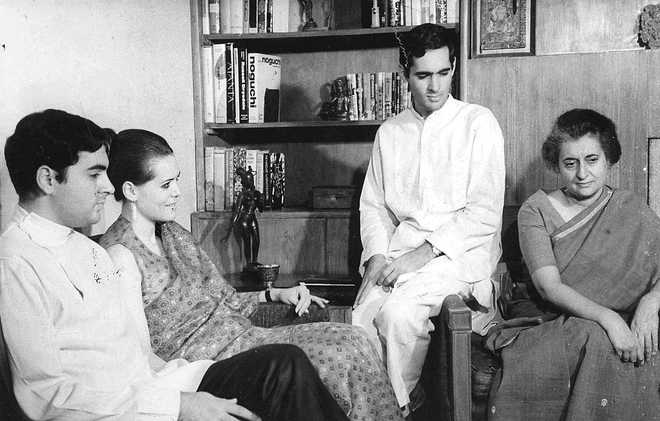

The closing weeks of the election campaign of 2019 have had a surprise topic: Rajiv Gandhi. Though he was assassinated nearly three decades ago, the legacy of the country’s youngest Prime Minister was brought to the centre stage by no less than the present incumbent.

It is unacceptable in our culture to speak ill of the dead. However, few parties have met the standard and, sadly, the larger the party, the greater the tendency to confuse invective with debate.

At the heart of this was an old time-tested strategy: to redefine the mission statement of the ruling party as one of making a better India or of governing it better but of ridding it of dynasty politics.

There are two riders to the claim. One, that the family steered India away from core Indian — read Hindutva — values. Two, that to redeem and reclaim India, such practices should be set aside.

Yet, history is witness that there has been only one instance of the office of Prime Minister passing from a parent to offspring and that was in 1984. True, there was a major turning point in the history of the Congress and the country eight years earlier. During the All-India Congress Committee session, Indira Gandhi said of the Youth Congress, “You have stolen our thunder.” No one had any doubt that the reference was to her younger son, Sanjay Gandhi, who was to die in an accident in the summer of 1980.

History is witness that the presidentship of the Congress in Lahore was bestowed on Jawaharlal Nehru not by his father Motilal but by Gandhiji. The movement, he felt, needed a young, more assertive face and the new head acted not merely in accordance with his own tenets but also by the collective will of the Congress Working Committee.

The three occasions prior to 1947 when he served as head of the party, there was never any doubt that the core organisation was controlled by Sardar Patel. But the choice of the leader by Gandhiji was accepted by all.

Under Nehru as Prime Minster, his daughter, Indira Gandhi, was indeed a key figure and served as party president in 1957-59. But there was little question of her being in the race for succession. Lal Bahadur Shastri, as Minister without Portfolio, rejoined a depleted Cabinet, with most ministers having left under the Kamaraj Plan.

Shastri's tenure was cut short by his sudden death at Tashkent, but as his biographer LP Singh shows, he was no pushover. Even Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, who was a stern in-house critic, publicly hailed him for his stellar leadership in the 1965 war.

His slogan of ‘Jai Jawan, Jai Kisan’ is today laid claim to by more than one party. In fact, as Information and Broadcasting Minister, Indira Gandhi was outranked in the Cabinet by more eminent figures, such as Morarji Desai.

Her own succession, as recounted in the 1987 biographer by veteran journalist and author Inder Malhotra, was largely due to the efforts of Kamaraj Nadar, the head of the party who earned the epithet of kingmaker. It is only in the wake of the Congress split and by the 1971 war that she emerged as a paramount leader.

In effect, the Congress, in its long history until 1976, did not have a tradition of family-centred leadership. Far from being an all-powerful PM, Nehru had to contend with powerful figures such as Partap Singh Kairon of Punjab and Dr Bidhan Roy of West Bengal. Many of these were men of the old Congress right: they read the monthly letter from the PM but often ignored what he wanted them to do.

It was the power struggle between the regional chieftains and the Prime Minister that led to the split and eventually to the creation of effectively a new party by 1972. The power vacuum enabled Indira Gandhi to propel first Sanjay and eventually Rajiv to the centre stage.

Terms like dynasty may apply in political parties, but do they have any relevance in a democratic country? After all, the tallest of leaders of the most powerful families have bitten the dust at the hustings. In March 1977, Indira Gandhi lost by over 1.5 lakh votes in Rae Bareli, held by members of the family since 1957 with no break. Her son, Sanjay, was trounced by RP Singh of the Janata Party by over 50,000 votes.

And it was as late as 1998, seven years after her husband's death that Sonia Gandhi entered the bull ring and that too only after PV Narasimha Rao bowed out of not only premiership and Congress party presidentship but also public life.

The fact is that any member of a powerful lineage or clan has a head start in politics but success depends, as with all other leaders, on how far they rally support. Outside some small pockets, this cannot and will not be possible simply via appeals to the past.

Does this mean family does not matter? Far from that. It does and has come to matter more since the late 1960s for another reason. Parties not built on cadre lines have tended over time to allow clan, lineage and community ties of kinship to become more central.

So, the Congress, far from being alone, is now in the company of most parties. The challenge for the oldest party is to prove that it is at one with the people at large. Those who emerged from the Nehru family succeeded only when their message struck a chord.

Perhaps, the issue is a different one. The Congress, in its present form, has been open enough about its limitations and has forged alliances in six major states. Modi is evoking an anti-Congress sentiment in his outreach to other parties as much as to rally the Sangh cadre.

The problem is anti-Congress ideas mattered most when it dominated the polity. Today’s fight is not democracy or dynasty, but for the soul and heart of democratic debate.

It is the vibrancy of open debate giving way to the all-or-nothing view that relives the past in its own mirror. We are in the 21st century. It is best to resist the mindset and battleground mentality of the 12th century.

The language of inquisition and show trials long ended elsewhere. India is better off without it.

(Views are personal)

Unlock Exclusive Insights with The Tribune Premium

Take your experience further with Premium access.

Thought-provoking Opinions, Expert Analysis, In-depth Insights and other Member Only Benefits

Already a Member? Sign In Now