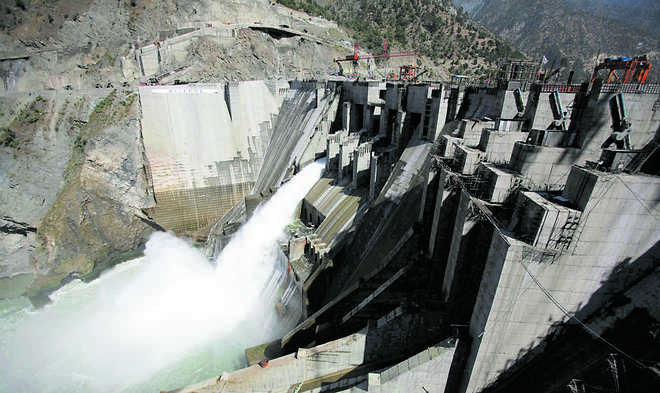

India and Pakistan’s Indus Waters Commissioners are expected to meet later this month in Pakistan, though the dates of the meeting have not been announced as yet. India’s decision to allow the commission to meet could only have been taken with a nod from Prime Minister Narendra Modi himself. Does it connote a softening in the hard but appropriate approach he had adopted towards Pakistan after the Uri attack in September last year? Besides, will this meeting have a bearing on the impasse that has developed between the two countries in resolving their differences over the Kishanganga Hydroelectric Project (KHEP) and Pakistan’s objections on the Ratle project on the Chenab?

During the recent Punjab Assembly election campaign, Modi asserted that India would use all the water assigned to it under the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT). In actual terms, it means using the full potential of the Ravi, Beas and Sutlej rivers, which are assigned to India in the treaty. In so doing, he became the first Prime Minister to refer to the IWT in these terms and that was correctly taken to be part of India’s post-Uri terrorist attack aggressive approach towards Pakistan. Importantly though, these assertions in themselves did not, in any way, mean abrogating the treaty or a departure from any of its provisions.

Clearly, Modi exercised care in formulating the remarks he personally made on the IWT. The comments attributed to Modi in a briefing meeting on the IWT that was held eight days after the Uri attack went beyond what Modi has said himself on the treaty. Sources told the media that Modi had made it clear that blood and water cannot flow together and that the Indus Waters Commissioners could only meet in an atmosphere free from terror. All this obviously sought to convey the impression that Pakistan should not take India’s commitment to the IWT for granted.

Major terrorist attacks against Indian army installations took place after the Uri attack, though since General Qamar Bajwa took over as Pakistan army chief after the retirement of General Raheel Sharif in November last year terrorist attacks have abated and provocations along the Line of Control and the International Border have also come down. However, there is no indication that Pakistan has done a rethink on the pursuit of low-intensity war against India. In these circumstances, the permission given to the Indus Waters Commissioners to meet indicates that particularly the remarks attributed to Modi in the wake of the Uri attack were part of the domestic political management exercises that successive Indian governments have undertaken after major Pakistani terrorist strikes. The twists and turns that Indian governments take as part of such political management only reinforce Pakistani prejudices about India’s lack of stamina.

The question now is will India show stamina in insisting that the provisions of the IWT be adhered to in the settlement of differences over KHEP and the Ratle project? This is especially when by agreeing to the meeting of the Indus Waters Commissioners India is respecting the treaty. Article VIII (5) mandates that the commission shall meet at least once a year, but also when requested by either commissioner. The background to the KHEP and the Ratle project disputes as well as India’s hitherto forceful and correct stand were given by this writer in these columns on January 9 this year.

Over the past two months, the World Bank has attempted to resolve the impasse that threatens the IWT. Its new CEO, Kristalina Georgieva, visited Pakistan in end January and India last week. In Pakistan she met Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and his colleagues. Predictably, they maintained that KHEP and the Ratle project violated the IWT and insisted on the convening of a Court of Arbitration to resolve the dispute. However, the World Bank “pausing” the untenable dual track approach it undertook continues to seek to find a way that the two countries will accept and then formally move it under the bilateral dispute resolution mechanism envisaged by the treaty.

In this context, the Bank’s official media release of Georgieva’s discussions in Pakistan on KHEP and the Ratle project is revealing. It states, “Maintaining a neutral role as a Treaty signatory the World Bank in December announced a pause in the separate processes initiated by India and Pakistan under the IWT to allow the countries to consider alternate ways to resolve their differences.” It invoked the spirit of the treaty and cautioned, “Pursuing concurrent processes could make the treaty unworkable over time.”

The fact is that no extent of obfuscation can hide the mess that the World Bank has made in handling Indian and Pakistani differences over KHEP and the Ratle project. Neutrality cannot imply avoidance to make a determination that under the IWT provisions, the Indian request for a neutral expert to go into these differences was correct and the Pakistani demand for a Court of Arbitration was not sustainable. If the treaty were now to become unworkable because of current differences, then the onus for the failure would lie not only on Pakistan but on the World Bank too. This would be ironic, for the Bank played a principal role in the making of the IWT.

Pakistani media reports indicate that it is not interested in the commissioners trying once again bilaterally to find a resolution to differences on KHEP and the Ratle project. This may be mere posturing or a way of putting pressure on the World Bank to seek concessions from India on the design of the project and the volume of water in the KHEP reservoir. Re-engaging Pakistan bilaterally on the current differences is in keeping with India’s overall emphasis on direct talks between the two countries on all outstanding issues. However, while doing so it is not only essential not to concede ground on the position that India has taken on substantive issues but also to insist that it would be without prejudice to its position on the neutral expert.

Pakistan has mismanaged its water resources. As Tilak Devasher notes in “Courting the Abyss”, his recent excellent study of Pakistan, “Pakistan has become a water-scarce country from a water-abundant one in 1947. It is in danger of becoming an absolute water-scarce country by 2035.” Instead of taking steps to ameliorate its water situation, it blames India for denying its share of the waters under the IWT. However, as Devasher reveals, Rao Irshad Ali, chairman of Pakistan’s Indus River System Authority, repudiated these charges. He told the Pakistan Senate in July 2015, “Reports in media about India getting more water is propaganda.”

The writer is former Foreign Secretary

Unlock Exclusive Insights with The Tribune Premium

Take your experience further with Premium access.

Thought-provoking Opinions, Expert Analysis, In-depth Insights and other Member Only Benefits

Already a Member? Sign In Now