Nonika Singh

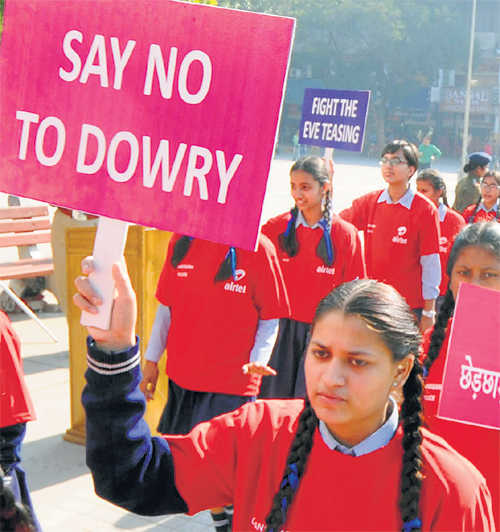

As far as laws go, Section 498 A, commonly known as the anti-dowry law or dowry harassment, is the most maligned. Ever since it came into being, one perception is that it is an instrument in the hands of manipulative women who use, nay misuse it, to get even with their husbands and in-laws.

Men's right organisations' standing grievance is that women file false complaints against their spouses. The popular perception -- that anti-dowry law is anti-men (read husbands) -- is so prevalent that even judiciary is not immune to the all-pervasive sentiment that stems from a patriarchal mindset.

Why else in July would a Division Bench of the Supreme Court direct that no action be taken on dowry complaints without ensuring the veracity of the allegations? However, as activists saw red and sensed a dilution of the law, the apex court revisited what the Bench had earlier stated.

In the 21st century, women's empowerment is certainly not just a chimera. Yet, the positive change in women's status seems to have little bearing on the custom of dowry, never mind that the practice was banned in 1961. Rather, with each conspicuous wedding it gets new lease of life legitimised by social mores which change only in appearance, not in essence.

Rather, over the years, it has become synonymous with girls' pre- mortem inheritance right. Daughters too fail to see behind the veneer of designer sarees and lehngas and have deluded themselves into believing that dowry is only a harmless addendum to a fancy wedding. They go along with the shenanigans, gladly unmindful of its detrimental fallout on their marital life. Why educated women too can't take a firm stand against dowry finds sustenance in arguments such as marriage squeeze. It states that despite a skewed sex ratio, there is a numerical surplus of marriageable women over men.

Perhaps, what has changed is that more women are ready to invoke the provision of the law if things don't turn out the way they imagined. But it is a misreading of the situation to say that each time a woman knocks the doors of court armed with the penal provisions of the law that makes the offence non-bailable, she is faking it. Statistics don't prove it. The data on domestic violence stands exactly on the contrary.

Above all, it's conveniently forgotten that dowry by itself may not be a violent practice but it does engender violence and undermines women's position in society. Violence against women shows no signs of ebbing. According to the NCRB, incidents of marital violence are rather high and the redress negligible. In 2015, as many as 7,634 women died in the country due to dowry harassment.

Till as a society we learn that dowry itself and not just the excesses emanating from it is a crime, Section 498 A can only be watered down at the peril of the fairer sex.

A fraction of women might use it to settle scores, but for a large majority, it will remain some sort of a shield. The latest figures dispel the notion that Section 498 A is an armour that gives women an unfair advantage in the battle of sexes. If charge-sheets were filed in 93.6 per cent of cases, only 14.4 per cent resulted in conviction.

The practice of dowry is heavily loaded against women and we need more, not less, laws which challenge its endemic existence. To deny its pernicious effect would be missing the point and its reach.

Its tentacles have reached far and wide. Even Australia is preparing historic dowry abuse laws, especially for the Indian community. Australia, which receives 50 dowry complaints a year, will become the only country, apart from India, to have anti-dowry laws.

Can India afford to look the other way on the serious issue of exploitation by husbands of the dowry system? Or look elsewhere and shift the blame at the feet of the victim? The Supreme Court bench headed by Chief Justice Dipak Misra is relooking at its own order issued by another Bench on July 27, 2017.

Section 498 A was inserted in the IPC in 1983 to lend teeth to dowry prohibition. In 2017, adding a caveat to ensure it doesn't become an all-guns blazing weapon isn't a bad idea per se. But like all laws in India, the fault lies in implementation. What is needed is efficiency and empathy at the police level. Society, meanwhile, must recognise the malaise that dowry represents. Eradicating the social menace rather than the law that deals with it is the answer and would serve men's interests, too. After all, men as fathers and brothers are dowry givers too. Since legally both giving and taking dowry is a crime, it's time both parties steer clear of the dowry trap.

nonikasingh1@rediffmail.com

Unlock Exclusive Insights with The Tribune Premium

Take your experience further with Premium access.

Thought-provoking Opinions, Expert Analysis, In-depth Insights and other Member Only Benefits

Already a Member? Sign In Now