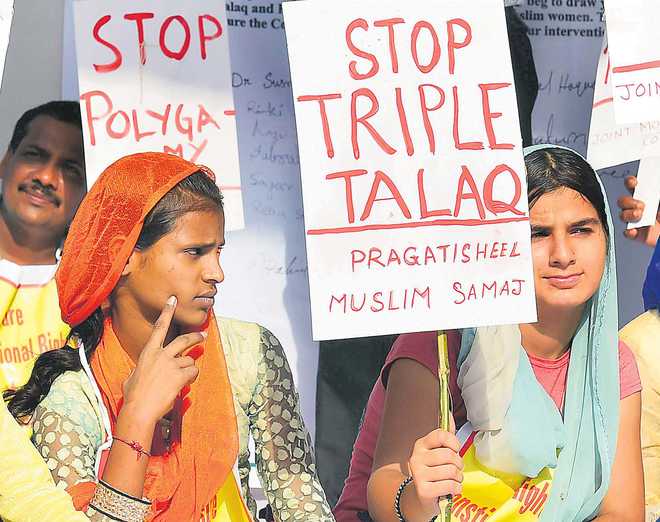

THE debate of triple talaq veers between the politics of hope and fear that surround not only gender, religious-cultural identities but also the electoral juggernaut of the BJP assuring a “package of deliverance”.

A global phenomenon

The larger issue in this discourse is the struggle for gender rights in a diversely patriarchal society and safeguarding religious and cultural identities that in large part stand out as different in their rituals, traditions and practices of marriage, divorce, inheritance, dress, and reproductive life.

While the multifarious gender bias customs are more peculiar to the Indian subcontinent and Africa, religio-cultural tensions and leverages are not specific to Indian politics now or earlier but are found globally. No doubt the political context is charged with the politics of cow slaughter, the shadow of the Uniform Civil Code (UCC), cross-border terrorism and reconfiguration in the electoral vote bank with stated shifts in Muslim women loyalties. The infamous over-riding of the Shah Bano judgment by a Parliament led by Rajiv Gandhi made its associations with conservative Muslim leadership an open effort to secure their vote bank.

Liberal democracies such as the UK, US and much of Europe have also been contending with the fallout of both extremes — ignoring gender abuse or making it a pivot for relations with minorities. In 1969, the British courts turned down an appeal for a care order of a 13-year-old British Nigerian married to a 26-year-old Nigerian living in London on grounds that it was “entirely natural”in their country of origin. It took the anti-immigrant agendas of the twenty first century to draw out protectionist measures for forced marriages and honour crimes in the migrant communities to mark and filter for the “egalitarian” British citizenship.

The present government's pursuit of women's rights is a welcome initiative. Women are inclusive to its development agenda — there is a policy thrust and programmes for gender equality, albeit on selective issues — beti bachao, provisions for sanitation, livelihood support. Women's safety has been made an indicator of good governance, so much so that women's interests are being shaped into an electoral constituency with the business of politics that of vote gain. These measures provide hope that the essentials will be delivered and rights protected but will local and cultural identities be nurtured? For these gender-related hopes to fructify a minefield has to be navigated.

The injustices of inaction

The current debate hosts a number of shadows of injustices. The discourse around triple talaq addresses a specific act of abuse, as has been the saga in India, whether it be dowry, sati or child marriage, seeking relief from one practice, targeting one section of women. The issue has not grown to confront women's safety in their homes much less safety per se — domestic or public. What about polygamy, female genital mutilation or rape in marriage that has been made a crime in 103 countries? The Bedia tribe cutting a swathe across central India has a family economy running on female prostitution and was notified as criminal by the British, yet there is silence in the corridors of reform on this tradition. If only selective acts from one or other communities are focused upon, does it not label and stigmatise these and by ignoring other routine abuse legitimise those acts? The decree of legislation tags a particular act as a crime but does not absolve the state from making these acts untenable in practice —after all dowry, domestic violence, sexual abuse, sex determination tests are all illegal yet rampant? The state enactment of delivery procedures and mechanism in response to a Nirbhaya has remained insufficient for justice to prevail. But the state is not the only arbitrator of our rights — our community gate keepers (boards, darbars and khaaps) — our clans and fraternities that create affinity, bonding and identity formation that are there to provide support in times of crisis must treat this as one and rally for justice. And lastly, there is a lesson of creativity and the art of the impossible in the story of electoral politics. If the “untouchable” Muslim vote has been broken into by the BJP by mobilising their women, it has been done by promoting a rights discourse.

Moving ahead

What can be done to steer through these lockouts when history and current adjudications record the continued plight of women? Some prerequisites need to be put in place. One, document and publicly place and debate all gender-unjust practices in India as a work in progress,taken up individually for legal reform and safeguards but advanced as a composite reform. Two, evolve a road map for all forms of gender violations to focus not just on entitlements but delivery of justice, improving access but also challenging social norms acting as hindrances. This opens a third front, requiring a thrust for research, policy and programmes to enable a comprehensive strategy. Four, strengthen local and regional stakeholding to usher in change nurturing a sense of belonging, participation and accountability. The right moves have been made for gender justice but these need to be inclusive in range, systematic in reach and persevering in effort rather than ad hoc, reactive or cursory to bring change in gender relations.

The writer is Director (Research), Gender Studies Unit, Institute for Development and Communication, Chandigarh.

Unlock Exclusive Insights with The Tribune Premium

Take your experience further with Premium access.

Thought-provoking Opinions, Expert Analysis, In-depth Insights and other Member Only Benefits

Already a Member? Sign In Now