Why no Sikh representative in UK house

THE recent British elections revealed two interesting facts worthy of note. The first, definitely good news, was that the representation of Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) Members of Parliament went up from 27 to 41 in the new Parliament, with roughly half of the MPs coming from South Asian backgrounds. This election also produced the largest number of MPs of Indian origin — going up from 8 in 2010 to 10 this time round and representing both Conservatives and Labour in equal numbers.

Culturally diverse

All of this is a great leap forward towards a more representative Parliament in a culturally diverse Britain. Secondly, bad news from my perspective, ever since 1992 there will not be a single MP of Sikh background, despite UK being home to around half a million Sikhs. The first Sikh MP, Piara Singh Khabra, was elected in 1992 but the 2005 general election produced three Sikh Labour MPs — Khabra, Marsha Singh and Parmjit Singh Dhanda. This came down to two in the 2010 election — Marsha Singh and Paul Uppal — representing Labour and Conservative, respectively. With the death of Singh in 2012, Paul Uppal became the sole Sikh representative but he also lost his marginal Conservative seat.

Explaining the absence

How do we explain the absence of Sikh representation in British Parliament and moreover, how is that the British Sikh community seems to be moving backward in this respect whereas other South Asian communities seem to be flourishing? Further, compared to the UK, other Sikh diaspora communities have greater success in the political process of their adopted countries. For example, the 2011 Canadian Federal election sent 8 Sikh MPs to the Canadian Parliament, despite Canada having a similar Sikh population to that of the UK.

Before offering explanations, it is important to emphasise at the outset that UK Sikhs, like other Indians, do engage actively in local politics. There are numerous city or borough Sikh councillors up and down the country, representing all the major political parties.There are currently even a handful of Sikh Lord Mayors. At the European stage, Neena Gill has successfully represented West Midlands as Labour MEP between 1999 and 2009 and since 2014.

Reasons for absence of Sikh MPs

Two explanations can be used to answer our puzzle. The first relate to the nature of the political process in the UK and Sikh participation. Historically, lengthy membership and activism in one of the three long-established and mainstream political parties, offers a reasonable chance of being nominated for selection to be a constituency MP. Labour has traditionally offered better opportunities but this has now changed dramatically, along with shifting voting patterns among Sikhs. Further, unless sitting MPs are stepping down on a regular basis, very few opportunities actually arise for selection. A history of party activism helps in the selection process but nowadays having a professional background and/or good connection with local communities or businesses, offers an important advantage.

It would also help if an aspiring individual chooses the political path right from an early age. Unfortunately, very few able and professional Sikhs have made that choice, preferring instead to focus on building careers or chase the pound. The combined effects of lack of opportunity structures — with most parties still reluctant to select minority ethnic candidates in winnable or safe seats — and dearth of Sikh career politicians means that Sikh names simply fail to get on the ballot paper. However, having said that, the election of Labour's Sikh MP Parmjit Singh Dhanda who represented Gloucester — an overwhelming “white constituency” from 2001-2010 — proved that the perceived risk factor may be exaggerated.

The second explanation relates to ongoing discourses in Sikh community politics. Since 1984, Sikh community politics have predominantly focused on looking backwards and inwards. The June 1984 Operation Bluestar, anti-Sikh violence in the aftermath of Indira Gandhi's assassination and subsequent Khalistan movement, divided Sikh communities along political lines and this has persisted to this day, especially given the fact that there has been no closure.

These divisions have created tensions which sometimes spill over into overt violence in some gurdwaras, as different groups compete to gain legitimacy and establish control over them. It is well known that Piara Singh Khabra, the first Sikh MP for Ealing Southall, was constantly vilified in Sikh political discourses because of his political stance against the Khalistanis.

Thus many religious-cum-political organisations vie for control over community institutions as this gives them an edge in setting the agenda for British Sikhs and “represent” them at various levels of decision-making. After the banning of Babbar Khalsa International and International Sikh Youth Federation, many organisations re-branded and tried to take leadership in mobilising support, especially among British-born Sikhs. This mobilisation is framed around highlighting injustices against Sikhs in India, exposing human rights abuses in Punjab and calls for self-determination among Sikhs. The highly partisan Sikh media — three TV channels, vernacular press and internet — also became an important site of contestation, giving voice only to particular perspectives.

As an example, the Sikh Federation, labelling itself as the first Sikh political party in Britain, although in reality acting more like a lobby group, has become highly active in the last couple of years. It has, arguably, claimed a number of “successes” — raising several early day motions in Parliament, facilitating several lobby days, initiating the first Parliamentary debate on the British Sikh community and co-organising a huge Trafalgar Square rally last year to mark the 30th anniversary of Operation Bluestar and anti-Sikh violence in Delhi. More recently, the Federation launched the Sikh Manifestoto to mobilise Sikhs towards voting strategically, urging them to only support those parliamentary candidates that partially or fully endorse their Sikh Manifesto and to oppose those that did not.

Mobilising Sikh vote

The Manifesto strategy, launched a couple of months before the election, appeared overly ambitious, especially as there is no single constituency with a high concentration of Sikh votes to have real impact, even if we assume all Sikhs will vote as a block. Which, of course, they don't.

However, mobilising the Sikh vote on the basis of the Sikh Manifesto may have had important repercussions at the local level. The Federation's campaign in the Wolverhampton South West constituency, with its large Sikh vote, estimated at anything between 8,000-10,000, inevitably proved divisive in that it split the Sikh vote — between Conservative Paul Uppal defending a small majority, and Labour's Robin Marris, a long-time supporter of Sikh causes in Parliament. More realistically, Uppal was beaten — he lost by 801 votes — by the combined effects of a fall in Sikh vote for Uppal, but more significantly by a four-fold rise in the UKIP vote which increased from 1,487 in 2010 to 4,310 in the recent election.

Sikh mandate

Thus, whilst the Sikh Federation may claim victory over a candidate who did not endorse their Sikh Manifesto, especially given its focus on injustices against the Sikhs, the Sikh community lost its only potential voice in Parliament.

Ironically, Paul Uppal had made history in 2010 by becoming the first non-white Conservative to represent the constituency which at one time was held by Enoch Powell, infamous for his anti-immigrant “Rivers of Blood” speech in 1968. Undue focus on homeland politics over domestic politics may also have played a part in the defeat of Tanmanjit Singh Dhesi, who was contesting as the Labour MP for the Gravesham constituency which also has a large Sikh electorate.

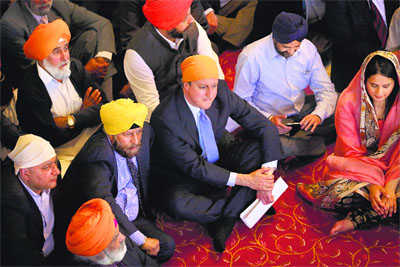

Dhesi seemed the ideal candidate with enormous potential: long history of Labour activism, highly educated, entrepreneurial success and well-connected to the local community. Fearing Dhesi's rise, David Cameron made a special visit to the Sikh gurdwara in Gravesend, the largest in Europe, to garner support for the Conservative candidate who was struggling for the Sikh vote.

The writer teaches Economics at Coventry University (UK) and is Founder-Editor of the Journal of Punjab Studies.

Dhesi became hostage to homeland politics

At the tender age of 32 in 2011, Tanmanjit Singh Dhesi became the youngest Sikh in UK to become Lord Mayor (of Gravesham). He quickly emerged as a favourite to become the first turbaned Sikh elected to Parliament. However, Sikh media's exposure about Dhesi's connections with ministers in the Badal government and his mother's conviction as co-conspirator with Bibi Jagir Kaur, in the alleged abduction and abortion case involving the latter's daughter, Harpreet Kaur, caused some concern among the tightly-knit Gravesend Sikh community. To the surprise of many, Dhesi lost by nearly 9,000 votes but unlike in Wolverhampton South West, this time, Labour vote was squeezed by a swing towards the Conservatives, probable split in the Sikh vote and a dramatic increase in the vote for UKIP, which rose from around 2.000 in 2010 to over 9,000 in 2015. So two potential Sikh MPs became hostage to homeland politics and lost. If there is to be a Sikh MP again, perceptions of major political parties towards ethnic minority voters and ethnic minority candidate selection, undoubtedly, need to change.More importantly, the attitude of Sikh organisations themselves also have to change. The idea that Sikh candidates who only subscribe to a particular viewpoint — perhaps related to homeland politics — will be supported, over those that may want to represent the interests of the local and wider Sikh community, needs serious introspection. Community interests need to trump partisan interests. Otherwise, the prospects of Sikh representation in British Parliament appear to be very bleak in the near future.