Shoma A. Chatterji

The Mary Koms, Mardaanis and Neerjas notwithstanding, Sultan starring Salman Khan, underscores the misogynistic ideology that underwrites most Hindi films especially the ones that revolve around romance on the one hand and achievement on the other. The very same Anushka Sharma, who began as Shah Rukh Khan’s ambitious wife in Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi and reinforced the strong woman image in NH10 surrenders her ambitions of an Olympic medal once she marries Sultan in Sultan. The rift in the marriage is not because she has second thoughts about her dreams but because she loses her baby and holds Sultan responsible for the tragedy.

The definition of a post-modern woman lies in its resistance to any fixed or rigid definition. Taani of Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi exudes an air of infinity and a plurality of purpose and persona. She reflects the post-modern lifestyle of the Y generation. Eight years later, Aarfa of Sultan goes one better. A young woman, who has gone all the way to prove her mettle in the boxing arena, goes soft at the knees once she falls in love and is married. Her focus shifts on resurrecting her husband’s career in the ring and on her motherhood. Sultan obviously finds it very convenient.

Barring few exceptions, mainstream cinema in India “has a “patriarchal, sexist and misogynistic” character,” says Ranjana Kumari, Director of Centre for Social Research and member of the National Mission for the Empowerment of Women. “Our cinema exploits the Indian psyche and the mindset that has sexist notions about women’s bodies and this is used and exploited by cinema. Barring some films, where women have been in lead roles or acted as protagonists, in most cases, women are used as a representation of good bodies. This is done to titillate,” she adds.

Love plays strange tricks for the woman in love or in marriage in Bollywood films. In Akele Hum Akele Tum (1995), Kiran (Manisha Koirala) is almost coerced into giving up her dreams of becoming a classical singer. But love and marriage takes her away from her aspirations. Though she walks out of her marriage and becomes a famous filmstar, it is suggested that she has destroyed the family while her estranged husband becomes the dutiful father forced to sell his music to keep his son happy and the home fires burning. Kiran comes back, giving up her career. Does she live happily ever after? No one knows.

In a scene in Dabangg (2010), when Sonakshi Sinha refuses the money offered by Chulbul Pandey, an arrogant cop, in exchange for some of the pots, Pandey says, “Pyar se de raha hain, rakh lo, varna thappad marke bhi de sakte hain.” If you think this, coming from a cop, is an extremely derogatory remark, you will be stunned with the girl’s response. “Thappad se dar nahin lagta hai sahib, pyar se lagta hai.” What does this suggest? That the woman takes a man’s unprovoked slap as if it is nothing to feel insulted about? This shows how deeply women have internalised this kind of physical and verbal insult. But the audience, mainly males, did not stop whistling and cheering, putting one more nail of disappointment on the coffin called “women’s empowerment.”

A UN-sponsored study by the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in media published few years ago examines “the visibility and nature of female depictions” in popular films across Australia, Brazil, China, France, Germany, India, Japan, Russia, South Korea, the UK and the US. Not only does India fare dismally when it comes to the percentage of female characters in movies, it also ranks high in the sexualisation of women in terms of sexually revealing clothing, nudity and attractiveness of women characters.

“Bollywood not only crystallises new beliefs but also reaffirms old truths. We have often come across popular projection in films where women are displaced and outcast when they are believed to have transgressed the rules of their father’s or husband’s house. What is more astounding is the fact that we have naturalised those responses, because the law has been unfair to women too,” writes Kanika Katyal in her piece analysing the bias against women characters in Bollywood cinema. (Youth Ki Awaaz, June 8, 2015.)

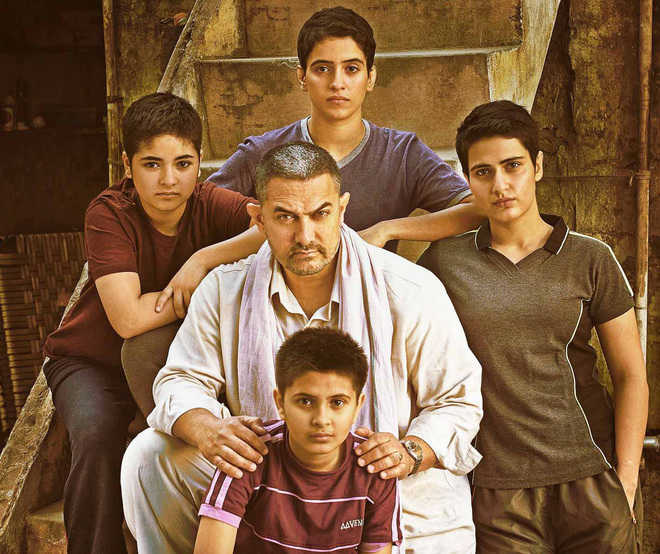

The poster of Aamir Khan’s forthcoming film Dangal has gone viral with thousands of ‘likes’ on the sites wherever the poster has been released. The poster shows a greying Aamir Khan with four young girls around him. They are all dressed like boys with hair cropped close to their heads, dressed in tees and trousers, their faces stripped of make-up resembling boys. Dangal, a local equivalent of kushti, is a biographical on Mahavir Singh Phogat, who taught wrestling to his daughters Babita Kumari and Geeta Phogat. Geeta, in course of time, became India’s first female wrestler to win at the 2010 Commonwealth Games while her sister Babita won the Silver. The funny part is — why would girls off the wrestling ring imitate boys in their dress, hairstyle and body language to prove that they are no less than boys? Place this against the same actor’s 3 Idiots where words like sthana (women’s breasts) and balaatkar (rape) are bandied about randomly as fun right through the film and the very intimate experience of a woman giving birth to a child is intruded into by three young men who are not related to the woman in any way up for grabs by a leering audience!

Unlock Exclusive Insights with The Tribune Premium

Take your experience further with Premium access.

Thought-provoking Opinions, Expert Analysis, In-depth Insights and other Member Only Benefits

Already a Member? Sign In Now