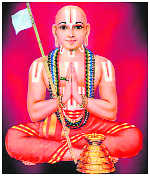

Ramanujacharya (1017-1137), whose sahasrabadi, 1000th birthday celebrations concluded recently, was a great spiritualist, humanist, and the foremost exponent of the qualified monistic school of Indian philosophy, called Vishishtadvaita. His vast erudition, dialectical skill, devotional outlook and sincerity of purpose, made him a living legend among philosophers and social reformers of his time. He opposed the exclusion of shudras and outcastes from worship in temples and at sacred spots. Being a true Vaishnava, he led a righteous life, free from human vices.

Born Ilaya Perumal, in Sriperumbudur near Chennai, Ramanujacharya (1017-1137) was a Tamil Brahmin hailing from the 10th century acharya tradition of Nathamuni, Pundarikaksha, amamishra Yamunacarya and Mahapurna, in successive apostolic order.

Ramanujacharya rejected the absolute monism (kevala advaita) of Adi Shankara, and argued that god is not impersonal but has innumerable qualities for universal wellbeing (ananta kalyana guna paripurna), like omniscience, omnipotence, benevolence and blissfulness. He regarded the universe of sentient and insentient beings as real, not the illusory projection (maya) of Brahman, the Transcendent Absolute. Instead of aiming at total absorption in god, as in nirvikalpa Samadhi, he preferred to savour the nectar of divine love in eternal relationship with Him.

Ramanujacharya accepted the existence of three eternal principles – chit (conscious), achit (unconscious) and Ishvara, the fundamental essence of both. He argued that the emancipation of an individual lies in complete faith in and surrender to God (prapatti). The devotee (bhakta) must surrender his self (swarupa smarpana), the fruits of his actions (phala samarpana) and all his burden (bhara samparna), to be able to experience god’s compassion. He held that individual souls (jiva-s) fall into three categories: the eternally liberated (nitya mukta), the liberated (mukta) and the bound (baddha). Those in last category could achieve salvation through the divine grace, which poured as a result of virtuous deeds.

Ramanujacharya was convinced that God is not a creation of the human mind but a living Reality that governs the affairs of mankind and of the universe. ‘If he is the whole (amsha), we are parts (amshi). If he is the controller (niyanta), we are the controlled (niyamaya). If he is the supporter (adhara); we are the supported (adheya).’ He visualised Vishnu or Narayana, with his consort Lakshmi, as representing the Supreme Being who has five forms: transcendent (para) emanations (vyuha), incarnations (vibhava), indweller in souls (antaryamin), and sacred image in temples (archa).

Ramanuja tried to harmonize the rituals of Pancaratra Agama-s with Vaikhanasa Agama-s but gave preference to the latter. His sect, known as Shri Vaishnava or Shri Sampradaya, underwent a split about two and a half centuries after his death into the Vadagalais (northern) and the Tengalais (Southern school).

The Vadagalais emphasised the study of Sanskrit while the Tengalais stressed on Tamil; the former believed in self-effort as a necessary concomitant to god-realization, the latter pinned faith in god’s love, which flows naturally towards devotees. To bring their point home, the former gave the analogy of the young monkey that struggled hard to seize its mother while she jumped from one place to another (markata-nyaya), and the latter, that of the caring mother-cat who served without being coaxed or asked (marjara-nyaya). The most erudite proponents of the two sects were Vedanta Deshika (Vadagalai) and Pillai Lokacharya (Tengalai). During his life Ramanujacharya is said to have founded about 700 mathas and 74 hereditary offices of religious preceptors. His name finds a place in the pantheon of deities in south Indian temples.

Among the works of Ramanujacharya are: Shri bhashyam, Vedanta dipah and Vedantasarah, all exegetes on Vedanta sutras; Gita bhashya, a commentary on the Bhagavad gita; Vedartha samgrahah, a collection of meaning of the Vedic hymns, Sharannagati-gadyam and Vaikunt?ha-gadyam, revealing the necessity of surrender to god and the ultimate destination of man in Vishnu’s paradise (Vaikuntha dhama), and Nitya granthah, focusing on the daily modes of worship.

Ramanujacharya regarded Bhakti-Marga, the path of attaining salvation through unconditional love and devotion to God, as synonymous with Upasana Marga that involves prayer and meditation. Both require constant remembrance (dhruva smriti) of the Lord which is possible by viveka, ability to distinguish between the impermanent and the permanent, vimoka, making the mind free from worldly cravings, abhyasa, steady practice, kriya, prescribed work, kalyana, welfare work, anavasada, freedom from despair, and anuddharsha, freedom from undue gladness.

Ramanujacharya reconciled love of god with love of humanity, and gave his message of bhakti to one and all, including apostates, as did the Alvar saints of Tamil Nadu during the 6th – 9th centuries. As a consequence, many outcastes attained to sainthood in time to come.

Dr Satish K Kapoor, former British

Council Scholar and former Registrar, DAV University, is a noted author,

educationist, historian and spiritualist based in Jalandhar City.

Unlock Exclusive Insights with The Tribune Premium

Take your experience further with Premium access.

Thought-provoking Opinions, Expert Analysis, In-depth Insights and other Member Only Benefits

Already a Member? Sign In Now