At the request of his father, Bhisham Sahni once dabbled in family business in his youth, and proved to be a miserable failure. Had he succeeded, Hindi literature would have lost a strong voice that spoke of the pain of uprooting of millions, of loneliness, of boredom, of egotistical demons hidden behind altruism and of political manoeuvrings of varied shades.

The canvas of Sahni’s writings was vast. He wrote in Hindi, but the spelling of his name remained Punjabi, the land he belonged to (Punjabi does not have half syllables). His daughter Kalpana Sahni, former professor at the Centre for Russian Studies at JNU, New Delhi, says earlier he signed his surname as the British pronounced it — “Sawhney” — but later changed it to the more native Sahni.

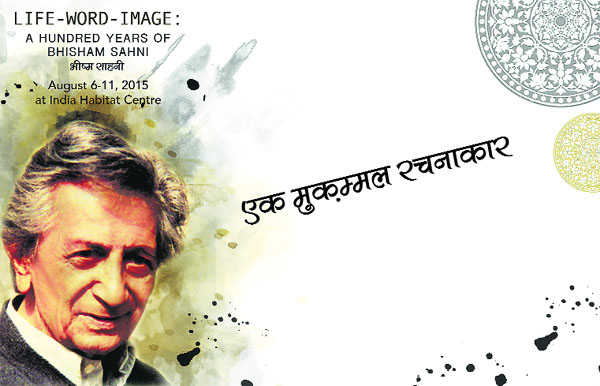

Younger brother of famous actor Balraj Sahni, Bhisham, an academic, actor, speaker, writer, playwright and social activist, was born in Rawalpindi on August 8, 1915. His clan came from Bhera, now in Pakistan, the locales of the town he powerfully evoked in one of his most popular novels Mayadas Ki Madhi.

The love for literature and fervour for social reform ran in the family, followers of Arya Samaj. His brother Balraj had taught at Shantiniketan and Gandhiji’s Sevagram in Wardha. Bhisham earned his Master’s degree in English Literature from Government College, Lahore. He took active part in the struggle for Independence; at the time of Partition, he was an active member of the Indian National Congress, and organised relief work for the refugees when riots broke out in Rawalpindi in March, 1947.

Passion for the cause of the common man turned him to Marxism; he travelled through villages and towns of Punjab with the IPTA (Indian People’s Theatre Association) group as an actor and director, barely concerned for his own survival. The power of theatre came across as a new realisation when he witnessed a woman remove her gold earring to drop in the jholi stretched before the audience, after a theatre performance in Rawalpindi, by a Calcutta theatre group in the post Bengal famine period, 1944.

“It was very different from all that I had been seeing earlier. That was my first introduction to IPTA… it told the story of the Bengal sufferers; the performance was charged with intense emotion…” he wrote in his autobiography Aaj Ke Ateet.

For a living, Bhisham worked briefly as a lecturer, first in a private college at Ambala and later at Khalsa College, Amritsar. In Ambala (then in Punjab), he became very active in the organisation of the college and university teachers’ union — work that spread across Punjab. Very soon, this led to his dismissal from the college on flimsy grounds. The union, however, elected him as the general secretary of the All Punjab College and University Teachers’ Union. “As he recalled in his autobiography, he ended up job-hunting and doing union work all over Punjab. Finally, in November, 1949, he managed to get an English lecturer’s job at Khalsa College, Amritsar, with a handsome salary of Rs 182 per month — a job that lasted a few months before he was asked to leave; once again, for his union work. That was the story of his association with Khalsa College,” recounts Kalpana.

In 1952, he moved to Delhi and was appointed lecturer in English at Delhi College (now Zakir Husain College), University of Delhi. He worked as a translator at the Foreign Languages Publishing House in Moscow from 1956 to 1963, and translated some important works into Hindi, including Lev Tolstoy’s short stories and his novel Resurrection. On his return to India, Sahni resumed teaching at Delhi College, and also edited the reputed literary magazine Nai Kahaniyan from 1965 to 1967.

This extraordinary journey endowed him with a reservoir of experiences, recollected in a pensive mood, a la Wordsworth — in his case, filtered through introspection which reached the readers of Hindi literature as distilled fiction. His prose was simple, it was honest to his characters, yet was layered with ambiguities.

Unlike his short stories on Partition, he wrote Tamas after Hindu-Muslim riots broke out in Bhiwandi in the 1970s, a painful reminder of the futile bloodshed of 1947. Govind Nihalani, who adapted Tamas, his novella on the Partition, into a classic for the small screen, says, “The time-lag gave him an approach that was very reflective and non-judgmental. His style was extremely simple. The entire event was recorded as a tragic event in human history. It was obvious that the book was written by someone extremely compassionate.”

Nihalani spotted Tamas at a bookstore in Delhi while working as the second unit director for Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi. After reading the book, he felt compelled to turn it into a film. “It was the best novel ever written on those times.” When he met the “very sensitive, gentle and warm-hearted” writer of the book, admiration turned into friendship.

Bhisham Sahni authored over a hundred short stories and several novels (Kunto, Neeloo Nilima Nilofar, Kadian, Jharokhe, Basanti, etc) and plays (Hanush, Madhavi, Kabira Khada Bazar Mein, Alamgeer, Muavze, etc), but strangely, he is remembered mostly for Tamas, perhaps because the visual interpretation became easily accessible, and also because writers those days did not go on promotional tours of books.

The characters scattered across the intense glimpses of life in his short stories breathe delicate human contradictions. His extraordinary ability to get away from the external darkness of the events to quietly sneak into the fissures etched on people’s psyche, to read the accidents of history happening in the hearts of his characters, turned We Have Arrived in Amritsar as a masterpiece. Pali, adapted and translated into many languages, has become more endearing for its innate humanism in the face of a calamity, despite the ludicrous fanaticism of both Hindus and Muslims. Or the satire of stories like Oob, the narrative of a professor who sits idle for three hours, counting strange things like chairs, the number of fans and ball pens; utterly bored, he decides to quit until he meets a watchman who has been sitting idle outside an office for 30 years. Yet, he wants his son to follow in his footsteps for it brings a fixed salary!

Many honours and awards followed Bhisham Sahni for his contribution to literature, including the Padma Bhushan for Literature in 1998 and Sangeet Natak Akademy Award for his contribution to theatre in 2001, and India’s highest recognition for literature, the Sahitya Akademi Fellowship, in 2002.

“He remained simple and gentle, yet warm and kind,” says theatre director GS Chani, who was a tenant in his Delhi house during his days of struggle. “He would get milk and bread in the morning and throw the garbage himself, it never ceased to amaze me,” he adds.

Sahni’s acting career launched him as a mute horse of Rana Pratap (brother Balraj enacted the hero in the play staged at home); then in school as Shrawan Kumar. He staged KA Abbas’play Zubeida in Rawalpindi with a mixed cast comprising cousins and friends upon his return from Bombay, where he was sent by his father on a “semi-spying mission” on the activities of Balraj and to persuade him to return home. But, Bhisham had become a convert, by becoming a member of IPTA. He is remembered for his memorable roles in serials and films like Tamas, Little Buddha and Mohan Joshi Hazir Ho.

The tragedy of Partition experienced by the family brought out deep compassion and humaneness, but it never had a shade of bitterness around it, says Kalpana. By forgiving the darkness and ignorance of the past, he distinguished his writing with the sensitivity of being human. And the person, Bhisham Sahni, retained his sense of fun and humour.

vandanashukla10@gmail.com

Unlock Exclusive Insights with The Tribune Premium

Take your experience further with Premium access.

Thought-provoking Opinions, Expert Analysis, In-depth Insights and other Member Only Benefits

Already a Member? Sign In Now