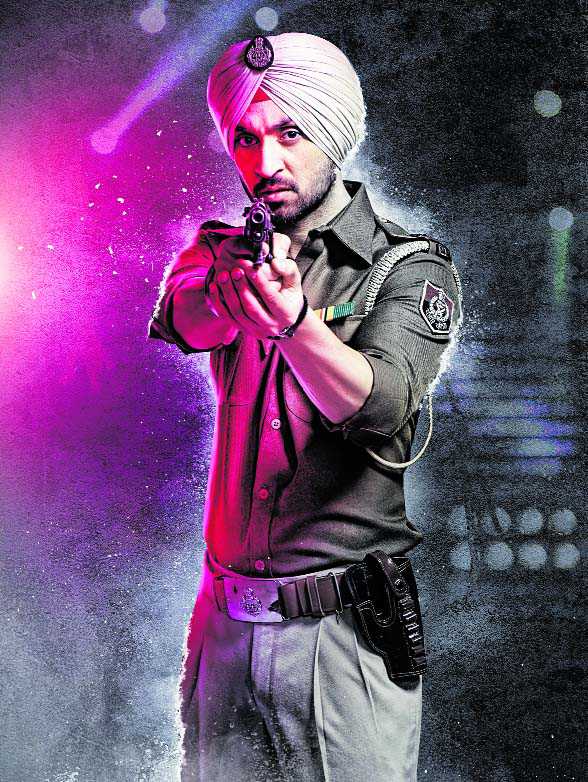

In the hallowed precincts of a Punjabi club in New Delhi, also known as the Sikh Club, day-to-day conversation revolves around the success of Udta Punjab that has taken the Capital by storm.

Udta Punjab is a film about the menace of drugs in the state. Those who have seen the film have enjoyed the vicarious satisfaction of sensing an undivided Punjab as existed before Partition, from Peshawar to Delhi. Although Punjab has been partitioned since 1947, the two Punjabs – one with Pakistan and the other with India – speak the same language.

The only difference is that the Punjabi spoken in west Pakistan has more Persian and Arabic words, while in India it is Hindi and Sanskrit that dominate. Yet 90 per cent of what is spoken on both sides is the same old Punjabi that was in vogue from the grand old days of Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

Now in the hope of harnessing old linguistic sentiments, Arvind Kejriwal has promised to boost the teaching of Punjabi in Delhi schools. Whether this will win his party a few extra votes in the forthcoming Punjab elections remains to be seen.

But at the very least he has stirred up some nostalgia about the old language among ethnic Punjabis living both in the state and in Delhi which has a massive Punjabi population.

On the fringes of the Chelmsford Club tennis courts, behind the light pink walls surrounding the swimming pool, some hardcore Punjabis mocked at my Westernized upbringing, accusing me of losing touch with my roots, including Punjabi. “Is that because you agree with our detractors who say this is the language of peasants”, one member asked. When l expressed my resentment at the negative implication, he challenged me to prove that l could at least still speak Punjabi.

So at the end of our tennis game and over a cup of tea, l took the courage of articulating what Punjabi l knew. To begin with l pondered how l should group together my vocabulary of key words and expressions. For example, start with all pronouns together, or give into the temptation of rolling out all words that started with the same letter, or grouping together well known curses.

In the end everything just seemed to spill out of its own accord, starting with simple words like ‘aaho’ (yes) ‘tussi’,‘tennu’, ‘twanu’ (variations of you or yourself) ‘mainnu’ (me) ‘sannu’ (us), ‘aider’/‘uder’ (hither and thither), ‘uchey’ (high), ‘neiven’ (down), ‘changa’ (good, or OK), vyah (wedding), labbo (search), ‘chhaddo’ (leave), ‘sutto’ (throw), ‘lootu’ (grab), ‘maro’ (beat), ‘kutto’ (hard beating).

I am no professor of Punjabi but eyebrows were raised when l mentioned ‘charokna’ (a long time ago). One ace tennis player said he hadn’t heard that word for a very long time.

More eyebrows were raised when l brought up naughty words like ‘lucha’, which means fiendish in character, or ‘kanjar’, which means pimp, or ‘moya’, meaning dead man. They are not considered appropriate for polite society.

There was pin-drop silence and all conversation stopped when l ventured into even looser words like ‘chudail’, meaning witch, and ‘khasma nu khaani’, which means husbands’ chaser. Some pejorative expressions like ‘satya naas’ are extremely hard to translate but suggest an end of being.

One of my tormentors finally conceded that l did indeed have a smattering of Punjabi. But determined not to give me any compliments, he remarked that my Punjabi was from Lahore, specific to that city and not spoken elsewhere.

“Where on earth did you pick this up,” he asked. “I did not dignify his question with a response, nor did l ask him to match my command over the language.

Unlock Exclusive Insights with The Tribune Premium

Take your experience further with Premium access.

Thought-provoking Opinions, Expert Analysis, In-depth Insights and other Member Only Benefits

Already a Member? Sign In Now