Karan Mujoo

When one thinks of Sector 22 in Chandigarh, one thinks of Kiran Cinema, rehri market, street vendors, and the paucity of parking space. But there is more to this sector than meets the eye. There is a row of booths, dominated by opticians, which hide a story in plain sight. A story which needs to be told.

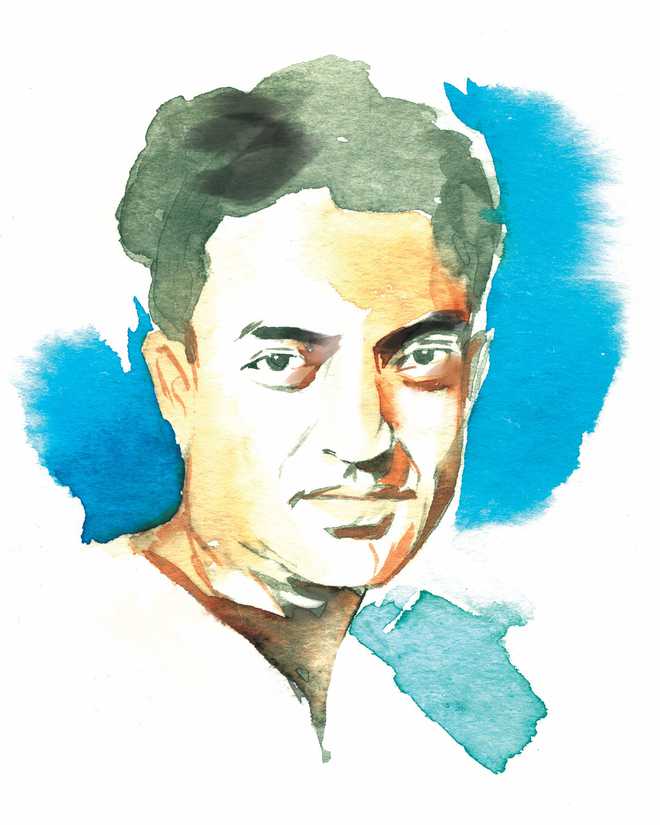

My fascination with these booths, and one booth in particular, started, strangely enough, on YouTube. During one of my YouTube binges, I chanced upon the interview of a handsome, young man. Curious, I clicked on the thumbnail. This man, it turned out, was none other than Shiv Kumar Batalvi. I had heard of him, of course. But for some reason, I had dismissed him as another one of the ancient, boring poets who were obsessed with rhyme schemes and metres. This seven-minute surreal interview proved how wrong my assumption was.

Everything about Shiv Kumar Batalvi was enchanting. The way his crystal clear voice rose and dipped. The way he swayed his hands while making a point. The way he threw his head back in angst and sang laments to the skies. I was transfixed. I wanted to know more about him.

Over the next few days, I scoured blogs, read books, liked Facebook pages dedicated to him. I heard Jagjit Singh and Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan Sahib sing his poems. I even sent his son a friend request.

During this intense period of research, I realised one thing. Shiv Kumar Batalvi was unlike any poet I had ever read. His verse throbbed with the pain of love. His words flowed strong and smooth like the waters of Beas. He was pure feeling. A conduit through which poetry flowed from the Gods to us.

His analogies were remarkable. In “Maye ni maye main shikra yaar banaya”, he compared his beloved to a hawk. Which other poet would show such audacity and freshness of thought?

In one of the blogs, it was mentioned that Shiv Kumar Batalvi was a regular visitor at ‘Preetam Kanwal Singh Watch Company’ in Sector 22. He used to sit at the shop, have a drink, recite his poems, and when tired, he’d sleep on a bench. I decided to see if the shop had survived the vagaries of time.

***

I squinted and tried to read the boards. Sandwiched between Arora Optical Co and Khalsa Confectioners, in tiny lettering, was written — ‘Pritam and Co’. I peered inside the shop and saw two Sikh gentlemen manning the counter.

I entered the shop and addressed one of them.

“Sat Sri Akal ji,” I said.

“Sat Sri Akal,” one of them replied.

“I am doing research on Shiv Kumar Batalvi. I’ve heard he used to come here?”

“Yes, he used to. Bilkul.”

I wasn’t prepared for this answer. I fumbled for my next question.

“Did you ever meet him in person?” I asked.

‘Meet him in person? Assi unna di ulti bhi chakki hoyi hai!’ one of them replied.

They said that their father Preetam Singh Kanwal, a writer, was friends with him. The brothers also told me that Batalvi used to get his drinks from a wine shop nearby.

The wine shop, too, like Batalvi Saheb, had disappeared with time.

I was unsure what to ask next. Seizing this opportunity, the gentleman behind the counter left for lunch. His brother, whose name was Saranjit Singh, waved me in.

“All these people who say they were great friends with Batalvi Saheb, they are all lying. He wouldn’t let anyone come near him. Nobody could match his talent.”

“What else do you remember about him?” I asked. “He was so handsome. Always well-dressed. Wearing his pathani sandals. I have seen how those college girls were after him,” Saranjit said.

“He even got us a Parker pen from England when we were kids. He was very close to our family.”

The clocks around us seemed to tick in unison. Saranjit, now quiet, it seemed, was travelling back in time. His expression saddened.

“The last time we saw him, his hair was cropped close to his head. He looked severely ill. All that drinking had finally got to him. While leaving he told my father, “Pappa ji, je jeonda reha te pher aavanga, nahi taan Sat Sri Akal.”

A few months later Shiv Kumar Batalvi died. He was only 36.

I sat there in silence, and looked at the bench where Shiv Kumar Batalvi used to sleep. Everything around me was so ordinary. Yet, not so long ago, this space had been inhabited by one of the most extraordinary poets in the world. I left the shop and lingered in the market for a bit. I wondered if people roaming with their families were aware of the history of these shops.

Their apathy hurt me a little, but then I realised that Batalvi was touching more hearts than ever before. With songs like “Ik kudi” and “Ajj din chadeya” his words were reaching far and wide.

As if on cue, I remembered these immortal lines of his and a smile broke out on my face:

“Gaman dee raat lami ae

Ke mere geet lamen nen

Na bherhi raat mukdi ae

Na mere geet mukde nen”

Your songs, Batalvi Saheb, are going to outlast these gloomy nights. Of this, you can be sure.

Unlock Exclusive Insights with The Tribune Premium

Take your experience further with Premium access.

Thought-provoking Opinions, Expert Analysis, In-depth Insights and other Member Only Benefits

Already a Member? Sign In Now