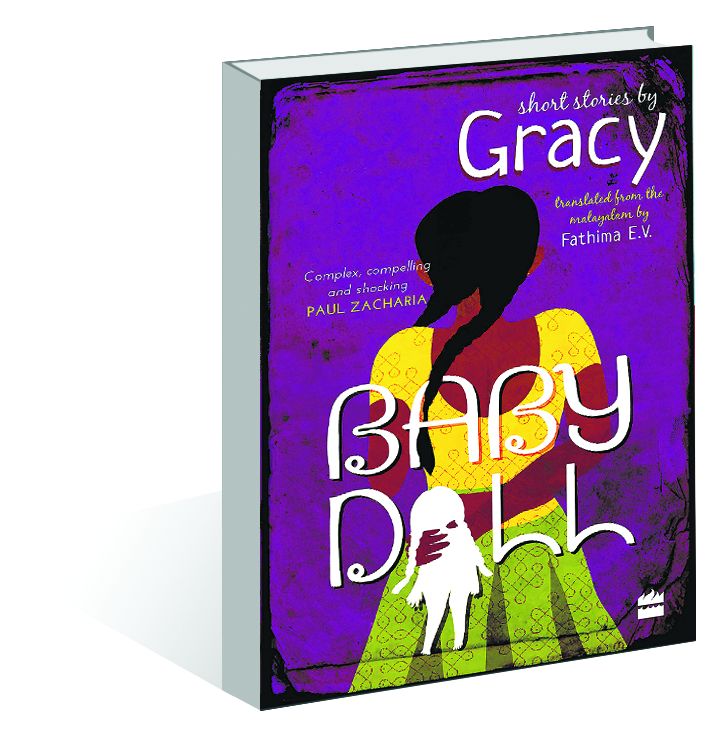

Baby Doll: Short Stories by Gracy. Translated by Fathima EV. HarperCollins. Pages 244. Rs 399

Book Title: Baby Doll: Short Stories

Author: Gracy

Harvinder Khetal

Marked by a racy, staccato beat, it takes a few short stories — spanning one page to three-four pages — before one gets accustomed to and starts admiring Gracy’s literary style. Each word and sentence is pregnant with a fervent intensity and imagery. And it is this economy of language that lends this anthology of stories translated from Malayalam to English a brilliance that truly radiates Gracy’s superb writing. In her note, Fathima EV, the translator, shares how it took hours to get over the most frustrating turns before the joyously rewarding phrases emerged. Readers of English now get to savour Gracy’s bold and unabashed take of the contemporary world and its ways and appreciate why the author is placed on the pedestal of modern Malayalam literary giants and has won many awards, including the Kerala Sahitya Akademi Award, in her kitty.

As the depth of each character unfolds and hits the reader like liquor shots in sudden wide-ranging spurts of emotions, it is the underlying dark, macabre theme gluing the collection of tales that leaves him awestruck and compels him to keep turning the pages of the book, ‘Baby Doll’.

Doom pervades the atmosphere, around which are woven in a hauntingly enchanting manner everyday lives of common women, girls, men, and boys. Even the dead, ghosts, animals and toys are tools that are frequently brought into play to lay threadbare the scars of conflict left by human inter-play. Trapped in situations oozing with desire, longing, hatred, misery, indifference, coming-of-age and intimate relationships, the battle of each character is depicted with shocking effect. The aridity of the contemporary society comes to fore as spunky protagonists — mostly females — defy patriarchal and misogynist norms with astonishingly unexpected twists in the tale. The vengeance unleashed, at times laced with lunacy, mostly leaves the arrogant male diminished. Staggered by the force of the startling denouement and metaphorical portrayals, the reader is often constrained to scan some passages again for better comprehension of the complex drifts. And, wonders why there is no relief from the morbidity, from the scary bylanes of laughter sans happiness.

The reader is rewarded with an answer to this query by Gracy herself in ‘This is Joseph’s Story; Anna’s Too’. She starts it with: “My dear reader, your question is my stories never traverse the luminous paths of life. It is not that you are not aware that all the paths of this world are being taken over by darkness. Since those responsible are human beings themselves, what is the point of being disappointed that I am not a storyteller who spreads light?”

The book gives a peek into the ebb and flow of the private worlds of mundu-clad Ammas and Ammachis, Echis, Chechis, and Chettahis, Achans, Appans. Dotted by a liberal sprinkling of Malayali terms and folklore, Hindu customs and Biblical allusions, Kerala’s landscape in the stories is variously reinforced by the sights and sounds of sea waves, palm trees, baby coconuts falling, toddy, cashew groves, black coffee, Gulf expatriates or the torch of dried coconut fronds.