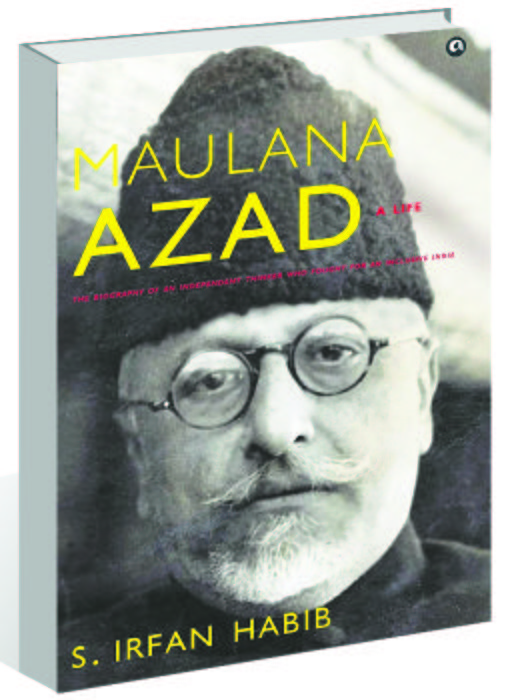

Maulana Azad: A Life by S Irfan Habib. Aleph. Pages 318. Rs 899

Book Title: Maulana Azad: A Lif

Author: S Irfan Habib

Salil Misra

Maulana Azad has had his fair share of biographies. The book under review, by S Irfan Habib, is different in the sense that it is not a chronological account of the important events in Azad’s life. Rather, it takes up four different dimensions of his engagement with the world both inside and outside of him. It describes the nature of his emotional and philosophic involvement with Islam. It talks about his life-long commitment to the politics of Indian nationalism. It highlights his contribution as Independent India’s first education minister. And finally, it provides us with a deep insight into ‘Ghubar-e Khatir’, an extremely unusual and atypical book Azad wrote as a prisoner in Ahmadnagar fort (1942-45) during the Quit India movement. The four themes are discussed in different chapters. These can also be seen as four different chapters in the rich and complex, and often troubled, life Azad lived.

Azad inherited Islamic values from his father. But soon was disillusioned both with the dogma of high Islam and the ritualisms of the folk and popular versions of the faith. Interestingly, he pursued his search for rational alternatives not through atheism, but from the rich philosophic traditions within Islam. In India, he was very inspired by the ideas and activities of Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, Jamaluddin Afghani and many intellectuals from the Delhi College. But his critical quest and a spirit of disenchantment came in the way of total acceptance of their ideas. In the end, he settled for a version of faith that was based on a selective acceptance of ideas from high Islam, eclectic Sufi traditions and also many features from other religious traditions. Through all the changes, he remained steadfast in his belief that a search for rationalism did not require going outside religion in general and Islam in particular. It was quite possible to find reservoirs of reason and truth in Islam’s intellectual and philosophic heritage. Azad’s deep involvement with religion was neither intuitive, nor a part of inheritance. It was the product of a long process of introspection and experiment. At some stage, he also considered giving up faith altogether.

Azad’s ideological commitment to Indian nationalism was total and uncompromising. But it was made up of very interesting ingredients. In the initial decades of the 20th century, ideas of pan-Islamism figured quite prominently in his Indian nationalism. It was partly the result of a global political climate in which ideas of pan-Islamism and anti-imperialism developed an eclectic affinity and went together, culminating in the Khilafat movement. But gradually, his nationalism became firmly anchored in the Indian context, and rested upon the twin pillars of anti-imperialism and Hindu-Muslim unity. This acquired great significance during the late 1930s and 1940s, when Muslim League’s demand for Pakistan as a separate Muslim homeland gained momentum. Azad fought tooth and nail against this politics of communalism and went on a vigorous campaign to propagate the ideas of Indian nationalism to Indian Muslims, risking humiliation and ostracism. In the end, Azad, along with his Congress colleagues, had to accept defeat when Pakistan became a reality in 1947. However, the strength of Azad’s nationalism needs to be judged in the light of what he wanted to achieve, rather than what he actually achieved. His utopia was much larger than the reality of the times.

As Independent India’s first education minister, Azad had hopes of achieving full or substantial literacy in a short span of time. It was a great priority with him, but its speedy implementation required enormous resources. Partition had cast its shadow on everything and important resources had to be diverted to relief and rehabilitation of the refugees, migrating from Pakistan to India. The first education budget of Independent India witnessed a 100 per cent increase from Rs 1 crore during the pre-1947 period to Rs 2 crore in 1948. This was, however, much less than the Rs 4 crore that Azad wanted for education. This slowed down the implementation of many of his favourite projects and schemes. Even so, Azad played a stellar role in creating a robust infrastructure, institutions of scientific and technological education, and for literary and cultural promotion.

Easily the most enchanting part of the book is the chapter on ‘Ghubar-e Khatir’, a collection of letters Azad wrote to his close friend from jail. The letters were subsequently published as a book, an extremely unusual one. Any reference to politics of the times is rare to find in the book, which is replete with references to literature, philosophy, religion and ethics. The influence of Persian poetry and philosophical traditions on Azad’s mind is quite palpable. The letters also refer to his passion for tea and music, and his close relationship with Jawaharlal Nehru.

‘Ghubar-e Khatir’ offers us a glimpse into Azad’s mind and life. Much more significantly, it transcends the limits of time and space and explores the larger questions of human nature, the search for meaning in life, the quest for harmony, riddles of religion, and many such philosophical questions. Perhaps no two books can be as different from each other as ‘Ghubar-e Khatir’ and ‘India Wins Freedom’, reminiscences by Azad on India’s freedom and Partition. The latter is an insider’s account — passionate, partisan and very personal. ‘Ghubar- e Khatir’ is just the opposite — reflective, from the outside, impersonal and cosmic. The fact that both these books were written by the same person, speaks volumes of the range, depth and the expanse of Azad’s mind. Above all, the two books exemplify his deep and intimate love for India, its people, culture and traditions.

The India of today is very different from the India in which Azad lived. It is also very different from the India he dreamt of. The book under review constantly highlights the contrast between the two. It is this contrast that gives the book its real salience.