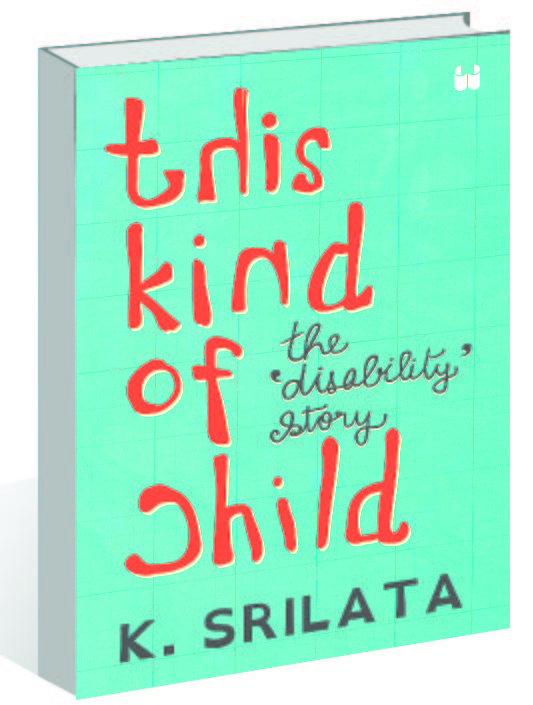

This Kind of Child — The 'Disability' Story by K Srilata. Westland. Pages 311. Rs 599

Book Title: This Kind of Child — The ‘Disability’ Story

Author: K Srilata

Harvinder Khetal

Digging into the lived experiences of her daughter Ananya, who did not fit into the school system for she made many ‘errors’, K Srilata weaves a myriad perspectives that she and many other persons with varying disabilities and their loved ones, caretakers and contacts encounter every day.

With every turn of the page of Srilata’s ‘This Kind of Child — the ‘Disability’ Story’, one increasingly understands and empathises with them as an entire universe of humans hidden in plain sight unfolds. Forming the larger conversation surrounding disability like pieces of a puzzle that fit together are interviews, short stories and first-person accounts chronicled by the author, who is a veteran poet, writer, academic and translator.

In a sharp rap to the ‘normal’ world, Srilata prefers the term ‘person with disabilities’ to ‘disabled person’ as she believes that a person isn’t a disability or a condition; rather, a person has a disability or a condition. Similarly, she avoids ‘special needs’ because of its condescending connotation, unless said so by the characters inhabiting the book. This, and so many other ‘instances’ — some even in ‘special’ or ‘inclusive’ institutions — jolt one into rethinking from the point of view of people with disabilities as they seek their own little ‘happy gardens’ in the jungle that we all inhabit. It certainly prods the reader into pondering questions that Srilata wants them to: “What does it mean to love and accept yourself or someone else fully? What abilities does it call forth? What new ways of being human?”

The title, too, acquires a new sheen as the writer shares with the readers how a little dyslexic girl is turned down by the principal of an alternative school for she could not possibly admit ‘this kind of a child’.

Tugging at the heartstrings is the lament of Ananya Kambhampati, a person with a learning disability; she says the insults hurled at her for scoring poorly feel like swords through her heart. Equally moving is the story of the unpleasant experience that Kristen Witucki, a blind person, had when she was rushed to the hospital to give birth to her first child. One also feels for Nisha, for whom darkness became a constant companion when, at seven years of age, her eyesight faded away irreversibly due to chronic malnutrition. But, incredibly, she discerns everything with touch, as if her fingers had eyes; she could also see with her ears and the pores of her skin.

The interview with Rajiv Rajan and Dheepakh PS gives an insight into cerebral palsy and how the two gritty men have charted independent and married lives for themselves, convinced by the dictum that ‘disability is not tied to charity anymore, it is about human rights’.

With sentiments running deep, Kim’s revelation of how coming out about the debitlitating disability related to gastrointestinal issues to the partner was like coming home is relatable. Don’t we all hesitate to speak about our own little diseases and disabilities? And, like in all families, without the need for expression, the partner takes on his duty of caring for Kim.

Kim’s poignant description of going through the “ODTAA syndrome — ‘One Damn Thing After Another’ — deeply bitter that this now applies to my own life” refers to the famous quote from Dr Atul Gawande’s book ‘Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End’.

How the conversation goes with Gayathri, who is on the autism spectrum, is another peek at the difficulties faced by such people while they work hard to do simple jobs and be understood. Equally moving are the episodes describing a child living with her polio-afflicted crippled father or a sister living with a brother with Down’s syndrome. Each story is a book in itself.

Interestingly, the author keeps the story open-ended as she believes that the people in her stories ‘will continue to grow, find other ways to inhabit the world’. After all, as she rightly puts in the ‘Afterword’, this community is also asking the question we all are asking ourselves: “What does it mean to live in this body, in this mind and navigate the world?”