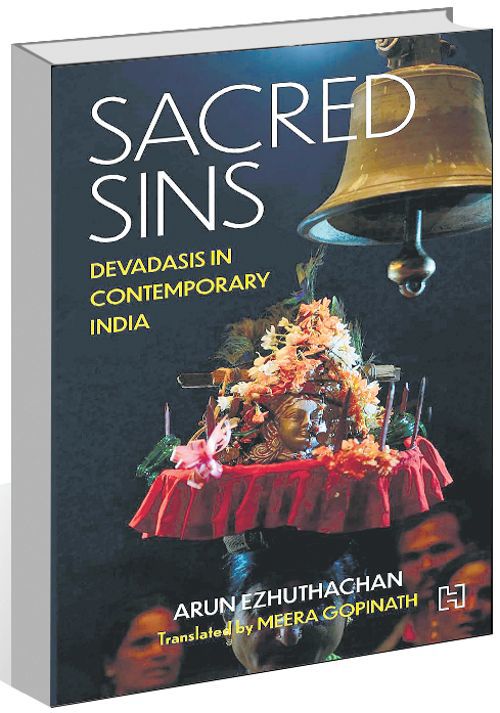

Sacred Sins: Devadasis in Contemporary India by Arun Ezhuthachan. Translated by Meera Gopinath. Hachette. Pages 242. Rs 799

Book Title: Sacred Sins: Devadasis in Contemporary India

Author: Arun Ezhuthachan

Sreevalsan Thiyyadi

Prakruti was in her mid-80s when Arun Ezhuthachan met the former Devadasi in Puri, Odisha. Till half-a-decade earlier, her job was to put her husband to sleep. By that she meant dancing before the deity at the Jagannath temple by the world’s largest bay. Devout Prakruti performed this duty till 2005 when she was 79 and a local ban was clamped on the age-old practice. When Arun met her amid his journalistic explorations, Prakruti was frail. She could only sing the verses — that without a quiver. Sitting on a mat in her ill-lit room up a stairway alongside a dingy pathway, Prakruti could well synchronise the mudras with the navarasa that used to glitter her eyes. Only, she was blind now.

Some 1,700-km northwest and 100 pages down ‘Sacred Sins’, a rickshaw-wallah in holy Vrindavan asks Arun if he wanted a woman. By that the puller meant his wife. “Just pay me 200 rupees,” he said, pedalling. “You won’t find lower rates in any ashram, sir.” It’s a hint at the underbelly of the city, where hapless widows from across the country continue to find refuge as lifelong devotees of Krishna. This is the very land that coloured the blue lord’s boyhood, going by mythology.

Jagannath and Krishna are two of Vishnu’s many forms. Just as hope and despair are facets of human life. Sometimes the two blur in interplay. Sandhya, for instance, is suddenly jubilant when she learns her questioner is from Kerala. Arun, like in any other place in the book, had reached Kolkata’s Sonagachi to interview victims of socio-cultural traps. The 30-year-old from Murshidabad bordering Bangladesh now senses a chance of tracing her boyfriend Sushant. The migrant labourer first met her as a client in the red-street pocket; and would then call her frequently from the southern state. Of late, there’s been no word.

‘Devadasis in Contemporary India’ is a sub-head Arun gives to his work that recently found an English translation from academician Meera Gopinath of Bengaluru. Stringing first-hand accounts that imply how ancient faiths sustain exploitation of women amid a “lethal combination of poverty, patriarchy and religion”, none of the 14 chapters suggests the prospect of systemic solutions. Indignant and feisty NGOs seldom manage to shrug off the apathy of governments or political parties.

Originally published in Malayalam in 2016, the work evolved out of Arun’s seven years of sequential travels. The rootedness of traditions leads him to realise the aversion the public has for reformations. A ban on customs never eliminates the underlying menace. Closure of illegal dance bars in south Karnataka’s Mangaluru following a 2008 court order reduced the entertainers to being prostitutes. One among them is Divya, originally from Davanagere — a hub of Devadasis. Arun’s visit to the Uchangi hill shrine there unveils how girls are made Devadasis on the ‘auspicious’ full-moon night of the end-winter Magh month. This, three decades after the Karnataka Devadasis (Prohibition of Dedication) Act, 1982. The Devadasi Liberation Front scoffs at a 2004 official survey that counted 23,000 such cult-servile artistes in Karnataka, claiming four critical taluks alone had 83,000 of them. Andhra Pradesh had in 1988 banned the sing-and-dance Bhogamelas owing to their sexual overtones, following which the Kalavantulu women of Rajahmundry ended up in the pleasure houses of Peddapuram, jostling with the rejects from Mumbai’s Kamathipura.

The reader may get sicker down the pages. Maybe the fatigue underscores good narrative skills. At times, Arun’s build-up of brothel atmospherics bears self-indulgence. His conduct with the prostitutes is suitably avuncular. Not to sound preachy adds to his burden.