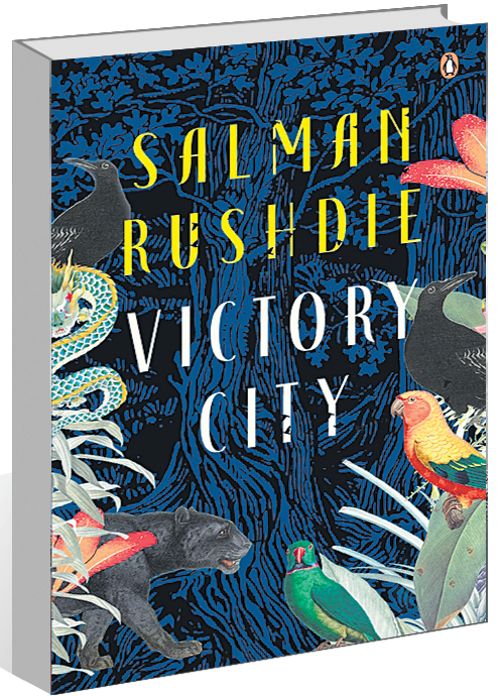

Victory City by Salman Rushdie. Penguin Random House. Pages 338. Rs 699

Book Title: Victory City

Author: Salman Rushdie

Shelley Walia

LEGENDS and myths often become archetypes of the rise and fall of civilisations. The element of storytelling has built into it the stories of civilisations, so exquisitely portrayed through the eternal element of imagination with the potential of turning travellers, tyrannical rulers and despots into powerhouses of fanaticism and dark evil forces. In the hands of Salman Rushdie, these turn into radiant accounts of not only historical significance but underscore the everlasting power of human language that innately survives through the undying human imagination.

How else would writers like Rushdie create masterpieces of historical fiction in a mode that is so close to the fabulous and yet speaks to every reader of the histories that the human race has experienced. Imagination indeed, in its eternal confrontation with the nightmare of history and the insatiable human impulse for creativity, has been a cure-all of our very survival through the triumph of the human spirit and art. It would not be out of place to mention here the survival of Rushdie from more than a dozen stabs in the dreadful knife attack he suffered from a Muslim fanatic in New York. Having dwelt on oppressors and carnage in his recent novel, ‘Victory City’, written before the assault, it almost seems that he had an uncanny sense of the approaching mishap. No wonder he had already hallucinated about it.

In the hands of Rushdie, once again in this feminist fable of love, adventure and myth, his dexterity with words remarkably stretches from the sense of violence and bloodshed to a metamorphosis into a vast and deeply scintillating magic of fiction, humour and reality interfaced with love and grief. This has continuously defined his theory of fiction whereby his exuberant tales have succeeded in coming alive with vivid characters and settings into which the reader imperceptibly begins to get immersed as if all that exists out there becomes the objective correlative of our very being. The victor and the vanquished, the factual aspect of history and that which is rewritten from the ideological perspectives of the ruling elite intertwine into what Hari Kunzru writes, “a joyous, messy excess… a triumph of life over forces of fanaticism and darkness”.

The story goes back to an insignificant battle between two kingdoms in 14th-century India where a nine-year-old girl by the name of Pampa Kampana loses her mother, only to be picked by a goddess as an instrument of her machinations to bring forth a history through the birth of the great city called Bisnaga (literally the victory city). Over the next 250 years, Pampa Kampana controls the fate of the city, striving to usher in a world where women enjoy equal rights with men, thus bringing to a close the dreadful sway of patriarchy. By acquiring the talents of using the potter’s wheel at a very young age, she learns the most important lesson of her life, “which was that there was no such thing as men’s work”, and that she must always laugh at death, never sacrifice her body like her mother to the fire, and instead, face life defiantly. “From blood and fire,” the goddess said, “life and power will be born.” And that Pampa would fight to make sure that “men start considering women in new ways”.

Pampa’s life remains constantly interwoven with the history of the city, but as external factors often have a way of coxswaining away from the dreams of dreamers, the city comes under the ravages of rapacious rulers. The hubris of power overtakes them, leading to the devastation of the city. Rulers come and go, victories follow defeats, follies weigh with wisdom, and fluctuations of alliances and political manipulations leave the beleaguered city in a state of bleak degeneration. The history of the land goes out of control and Pampa, nevertheless, struggles to stay at its core, but to no avail.

Nations indeed meet their tragic ends when rulers begin to forget “the triumph of non-violence in a violent age”. Love, adventure and myth resonate with the past and the present, as well as with the future of nations and their decline at the hands of those who hunger for ruthless and unconstitutional power over civil societies. The virtues of mutuality, of discussion, of recognising the rationality of the conflicting point of view seem to be recklessly dispensed with.

Though the larger lessons of the workings of history are laid tangibly before us, and though the locale of the novel is southern India, there is no affectation of being historical. The story evidently is a translation of an epic poem by the Empress Pampa Kampana who lived for 250 years. Pampa’s epic poem written in Sanskrit and which is “as long as the Ramayana, made up of twenty-four thousand verses” was kept hidden from history for one hundred and sixty thousand days during which “the memory of its history was ruined by the passage of time, the imperfections of memory, and the falsehoods of those who came after”. Salman Rushdie inspires through his narrative the struggle to regain the past, the birth of the Bisnaga Empire as it truly existed with “its women warriors, its mountains of gold, its generosity of spirit, and its times of mean-spiritedness, its weaknesses and its strengths”.

In the hands of Rushdie, the story becomes a simple entertainment for both the educated and the semi-literate, “the broad-minded and the narrow-minded, men and women and members of the genders beyond and in between… for humble sages, and egotistical fools”. And the translator is ostensibly Rushdie, who, as the narrator emphasises, is “neither a scholar nor a poet but merely a spinner of yarns”. The imaginary and the fantastic predominate in creating a remarkably exuberant epic tale that has within it rich echoes of the workings of the diverse ways of the state, its spells of hate and repression, as well as its notion of welfarism. There is history very much present, but it is ingeniously fictionalised by the author.