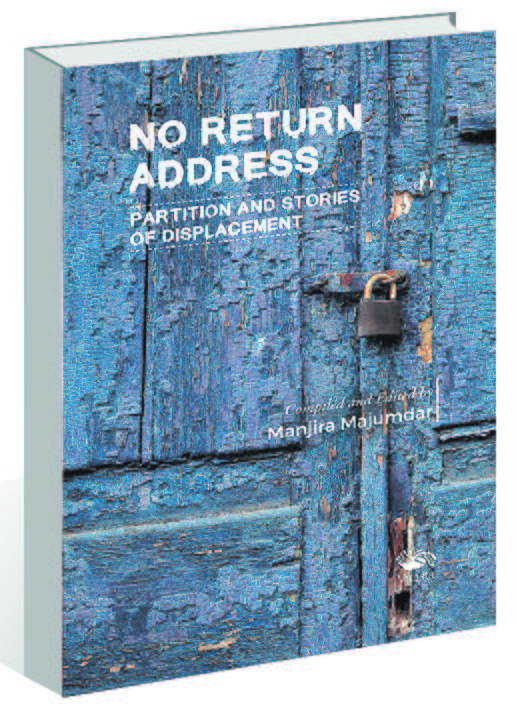

No Return Address: Partition and Stories of Displacement Edited by Manjira Majumdar. Vitasta Publishing. Pages 214. Rs 495

Book Title: No Return Address: Partition and Stories of Displacement

Author: Manjira Majumdar

Salil Misra

The composite linguistic zone of Bengal experienced four partitions in the 20th century. The first happened in 1905 when the Bengali-speaking people found themselves divided across different provinces. The second reversed the first, restored the linguistic unity of Bengal, but separated Bihar and Orissa from the larger Bengal presidency. The third was the big Partition in 1947 when the region was split and merged into the two nation-states of India and Pakistan. The fourth partition in 1971 established a separate nation-state of Bengali-speaking people. Bengali Muslims got separated from Punjabi Muslims but were not united with Bengali Hindus. The politics around religion, language and region created new boundary lines and redrew mental and emotional spaces. They would certainly have taken their toll on the collective psyche of the people. The written records and documents are, however, not very useful when it comes to making sense of this universe of ideas, beliefs and emotions. It is here that stories — combination of facts and creative imaginations — come in as a great window into this world of emotions and experiences.

‘No Return Address’ is a collection of 10 stories and a short novel which offer slices of three facets of human experiences — displacement, alienation, and belonging. Partition turned citizens into refugees. The refugee-ness was not just a condition, it was an experience. The big questions of politics and ideology, and nationalisms of various kind touched human lives in numerous ways. They sometimes created new choices for people; but often took away many choices from them. In one stroke, citizens became aliens; natives became migrants; insiders became outsiders; friends became foes; lovers became strangers. The stories talk about the predicament of people torn from their roots and searching for meaning and orientation.

There was Sheela whose great desire was to become a tree, firmly rooted in the soil and resistant to external pressures from the wind and storm (‘The Woman Who Wanted to Become a Tree’). Arushi always wondered about the great tenacity and volatility of a pressure cooker. It can bottle up emotions and release them gradually so as to prevent an explosion. But it can also explode inside out and scatter everything all over (‘Pressure Cooker’). Displacement can be a strange experience. It is one thing to be displaced from physical spaces, but quite another to be displaced from one’s memories as well. This double displacement was experienced by Alam, who lived all his life in Kolkata — his city — but was forced to migrate to Dhaka. Coming after a few years to Kolkata for a seminar, he must live in his own house as a guest. Once he gets into the house which was once his, he discovers that he has been displaced twice over (‘Alam’s Own House’). He had experienced that Hindus and Muslims, who were both together and estranged, had begun to think of each other as oil and water. No matter how hard one tries, the two cannot mix. Their resemblances are superficial. But Alam wondered — didn’t oil begin its life as water? How was it that the two became so un-mixable? When did water mutate into oil? It was in the great separation of oil and water that Alam lost the love of his life.

Then there was Jessica. She had her roots in Kolkata for as long as she could remember. But she was not a Bengali. She was fitted into the standard identity template of ‘Anglo-Indian’. But she was not an Anglo-Indian either. Jessica was a Portuguese who had never been to Portugal. Jessica was an alien wherever she could possibly be — in England, Portugal or Bengal. So where did Jessica belong? (‘About Time, Jessica’)

The stories offer slices from the lives of people torn away from their roots and floating involuntarily, driven around by the huge tidal waves of events not of their making. All the characters resemble birds in a storm, being flown away in multiple directions, determined by the storm. They have desires and feelings but no agency or choices. Each life is different. But they are all tied through the common thread of rootless-ness and a great desire to belong. These are stories without a conclusion or even a closure. But isn’t life like that only?