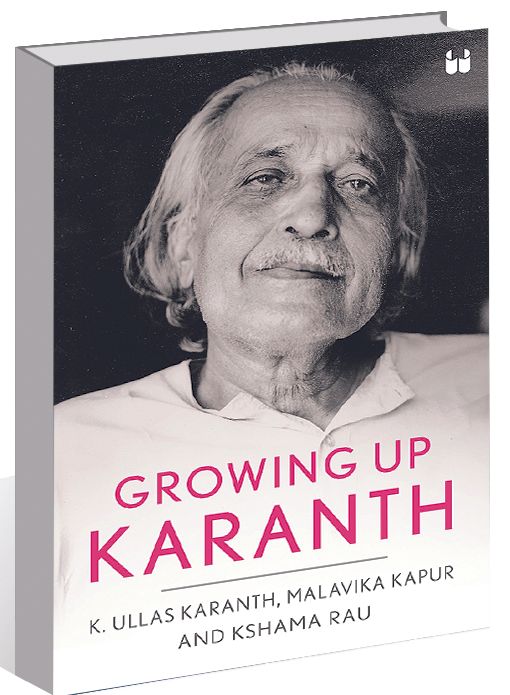

Growing Up Karanth by K Ullas Karanth, Malavika Kapur, Kshama Rau. Westland. Pages 242. Rs 699

Book Title: Growing Up Karanth

Author: K Ullas Karanth, Malavika Kapur, Kshama Rau

Neelam Mansingh Chowdhry

I met Shivram Karanth when I was in my second year at the National School of Drama in 1974. Even though I had never heard of him or about Yakshagana, a dance form that he had come to teach, I certainly knew that I was in the presence of greatness.

‘Growing Up Karanth’ is a radiantly powerful and beguiling biography that gives an insight into the life and times of Koto Shivram Karanth. It’s a warm and revealing book, abounding in images so vivid that a reader enters into the time and terrain of his life. Like a participant, I felt witness to the tumultuous noises of his domestic and creative spaces, bristling with life and brimstone.

The book is full of enchantment and anecdotal vignettes that make the reader ‘peep’ into the life of a man who straddled the world of literature, popular science, social activism, Yakshagana, and politics. Amar Chitra Katha stories were written by him in Kannada, illustrated, and then translated in English, with the credit attributed to the translator, an ironical reality.

A multidimensional man, with multidimensional qualities, it’s impossible to talk about him in singularity. One can only understand his genius in loops and swirls that fly in different directions, reconstituted, reassembled to present an iconoclast who stands tall in the pantheon of Indian artists, intellectuals and scholars.

Karanth was a formidable figure in Karnataka, but unfortunately, his genius and accomplishments are not so well known outside his state. The biography, written by his three children, will hopefully seal this gap. Karanth had four children; the eldest, Harsha, died in 1961. The other three, Malavika Kapur, Ullas Karanth and Kshama Rau, came together to write his biography which is certainly not a hagiographic eulogy of children who reminiscence their dead father. It is personalised, subjective and interpretive; with warts and wounds, nuts and bolts, and no attempt to valorise.

The three children have sometimes written about the same incident through their own individual experience, giving a kaleidoscopic perspective of a complex man with a complex mind. This method of inquiry was to gaze back on their own most powerful childhood experiences, and investigate these with compassion, framed within the unfolding social and political compulsions of the time.

The book has the shape, the quality, and the vividness of a conversation with the reader — a tale of people, places and events as they occur; colourful stories of his family members; the influence of friends and mentors on his life; the myths and mysteries that surrounded him; personal details, undisclosed until now, appear, transmuted and transposed in his art and his life.

One gets the feeling as if you have entered the Karanth household, smelt the varied cuisines, whiffed the aroma of the condiments drying in the sun, played with the pets, seen the shadowy light that filtered through the trees, with his beloved wife Leela Alva Karanth welcoming you with a calm and warm smile.

Leela comes across as a vibrant, impassioned woman, who anchored his life and very early in the narrative we get to know, she proposed to Karanth (as she disarmingly claims, ‘seduced by his beautiful hands’). Her descent into darkness due to loss of memory is told with moving poignancy and sensitivity, without slipping into sentimental pathos.

The setting for all this action is Balavana, their family homestead, which had its doors always open. This was where Karanth wrote and reframed Yakshagana, by hammering away the unnecessary coating it had acquired, pulling out its original impulse and making it palatable for a new generation, without compromise or subterfuge.

On a personal note, working with him was an unforgettable experience. As a student learning Yakshagana at NSD, I felt an irresistible pull due to his unbridled energy and wild spiritedness. He would walk into the studio theatre wearing a crisp white dhoti and kurta. Immediately on arrival, he would shed his kurta and dance madly with his dhoti billowing and his vest clinging to his body. The dishevelled white hair, which during dance classes would spray a shower of sweat when he pirouetted with feline abandonment, amused his students greatly. The two-month workshop culminated in a Yakshagana play, Bhishma Vijaya, based on an episode from the Mahabharata.

Karanth, with his large piercing eyes, like an X-ray machine, made us feel as if he could gauge your innermost thoughts. Such was his incisive charisma! An unabashed extrovert, his speech, laced with juicy colloquialism, debunked the mysticism attached to a guru/teacher.

In this brilliant and compelling biography, I read that Kota Brahmins (Karanth’s lineage) followed the Advaita philosophy, their primary deity being Narsimha, the half-lion avatar of Vishnu. An appropriate family deity to worship as Karanth resembled the grandeur of the lion, with his wild white mane and unflinching gaze that could both sear and endear.