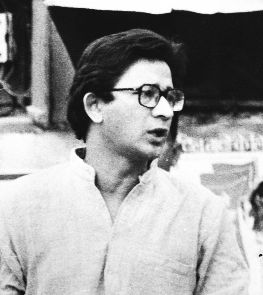

Book Title: Halla Bol: The Death and Life of Safdar Hashmi

Author: Sudhanva Deshpande.

Shelley Walia

“If you can feel that staying human is worthwhile, even when it can’t have any result whatever, you’ve beaten them.” — George Orwell, 1984

Born to a father with communist leanings, and a mother who loved art and literature, Safdar Hashmi joined St Stephen’s College in the late 1960s, and proceeded to do his MA in English from Delhi University. The egalitarian in him rejected the hollow elitism of St Stephen’s and provided the impetus for his move to the Student Federation of India (SFI), which dominated youth politics in Delhi University. Hashmi’s political journey to the Left had begun because the environment was ripe for those who “find ways of creative exploration”.

by Sudhanva Deshpande.

LeftWord.

Pages 264.

Rs 350

Politics or spectacle has always been performance art to some degree. But performance has often triumphed over substance. Leading politicians become superstars and young budding writers and artists find themselves incarcerated or snuffed out, as Hashmi was on that fateful day of January 1, 1989 when a pack of goons disrupted the staging of the street play Halla Bol in Jhandapur on the fringe of Delhi.

Hashmi was a founding member of Jana Natya Manch (Janam) formed in 1973, which grew out of the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA). When Indira Gandhi was indicted for rigging the elections, he produced a street play Kursi, Kursi, Kursi as a reaction to the storm. Machine was performed for workers on November 20, 1978, followed by Gaon Se Shahar Tak on the misery of small peasants.

Sudhanva Deshpande draws attention to Hashmi’s drama not merely as some remonstration but a sincere response to the conception of an art form for a just, equitable society launched at the grassroots and working its way upwards. Hashmi chose street theatre to directly address the people at the lowest strata, especially at a time when national politics in India, under the authoritarian rule of Indira, followed by Rajiv Gandhi, was in complete disarray. To break out of this usurpation of power at the highest level, Hashmi founded Janam.

Hashmi’s work arises from a well-defined function determined both by his ideology and his times. In addition to his experiential framework, the personal and social history, geographical location and the prevailing politics of the time become correspondingly relevant for an extraordinarily innovative methodology of grasping the truly meaningful and vital cross-currents that have a direct bearing on the production of political art. Drama for him enriches thought and action, and, permeated with a subtle and fuller expression of resistance, is utterly resolute against the state and its moral authority.

Belonging to a generation of the 1960s, the author evokes the times Hashmi lived in, acutely aware of belonging to a volatile period of youth intervention and the rising dissident culture. It is clear that Deshpande shares with his friend and comrade Hashmi a deep-seated commitment to democracy, a world embodying the ideals of liberty, equality and justice.

The book stands out for the use of imagination and the passion for dissidence that reflect our complete humanity. It is visible in Hashmi’s plays which represent a counterculture of the imagination that debates the nature of reality and defies the imminent danger of throttling and suffocating the imagination or an irreverent interrogation of the system. His death called for forceful attention to the need for an oppositional stand. As Moloyashree, Hashmi’s comrade and wife, says, “What happened then was not just an attack on freedom of speech, but on the right to survive. Today, alternative thought spaces—intellectual, artistic, and physical—are shrinking. One must fight against this kind of censorship.” For both of them, the political struggle did not exist separately from the artistic one. The form became the content and to Hashmi, especially, the material in which you wrap your ideas is aesthetically more appealing rather than the production of a sheer tendenz.

The killing of Hashmi ignited public outrage across the country, evolving a new lexicon that would confront contemporary politics, examining and questioning its social and historical circumstances. The struggle of these young writers and artists continues and I am convinced that the memories of that time so evocatively depicted by Deshpande will be cherished by future generations and provide the basis for not only the reenergising of street theatre but also renewing the campaign for social justice and freedom of inquiry so pulsating in the recent student agitation. Their fight, through non-violent anarchy, is a welcome forerunner to the days of liberation, love and equality.

We, who live today, have slowly begun to remember our history, and our poet’s songs. Deshpande, in a moving and incandescent account, has shown through a cultural and political history, how the personal more and more becomes the political, writing and acting become our praxis, and a life lived in art struggles to transmit the voices of the masses to the powerful for whom it is increasingly difficult to ignore the rising tide of “halla bol”.

Hashmi realised early in life that we need to evolve an aesthetic of resistance in times of fundamental transition. Herein lies our hope and our dreams. The words of Carlos Mejia Godoy, a Nicaraguan folk singer allied with the Sandinistas, come to mind: “For liberation/You are risen/ In every arm outstretched/To defend the people/Against the exploitation of rulers.” Though he died young, Hashmi’s spirit of commitment to aesthetics as a powerful means of emancipatory politics lives on.