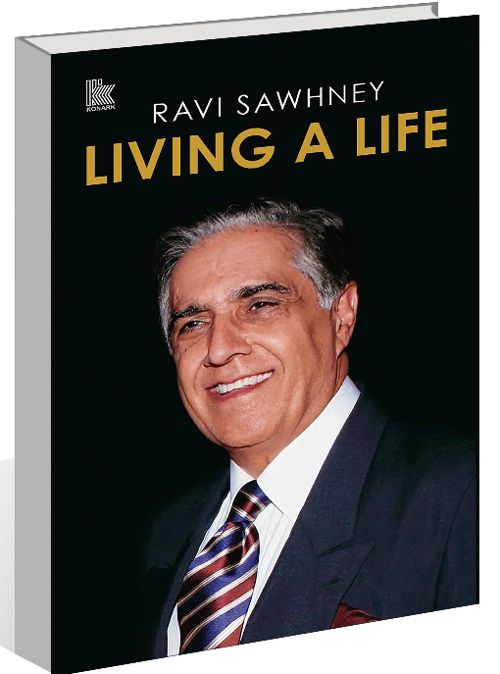

Living A Life by Ravi Sawhney. Konark Publishers. Pages 264. Rs 800

Book Title: Living A Life

Author: Ravi Sawhney

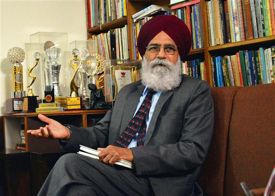

Amitabha Pande

IT is difficult to objectively review a memoir with which one’s own memories are so intimately intertwined. Ravi Sawhney’s ‘Living a Life’ narrates the story of four decades of a rich and illustrious career in public service, of which the first two were spent primarily in Punjab at a time when this reviewer was also a part of the same service. Our lives intersected often and Ravi became a close friend and mentor. His memoir, therefore, carries a special appeal for me.

Memoirs of members of the IAS are of interest both as intimate histories that provide a non-academic personal perspective on several important contemporary events, and as portraits of individuals who have had the opportunity to lead more diverse and interesting professional lives than is possible for most other career professionals. The diversity of the challenges they face, the bewildering variety of people they meet and interact with, and the pressures they work under make the memoirs of civil servants, very naturally, important documents of social, political and cultural history.

Ravi Sawhney tells a very honest story of an uncompromising, uncomplicated and straightforward man, narrated as simply and elegantly as the man himself. While he faced some occasional setbacks in his career, these were few and far between. The straightforwardness of the story is by itself an important dimension of the comparative straightforwardness of the times.

The memoir traces Ravi’s seemingly seamless movement from the districts to the state capital to the national capital and then on to international destinations. In his case, the seamlessness of the transition was not just an accident, it was a mark of his abilities to straddle many worlds with very different environments, different cultures and different kinds of work pressures with supreme ease. The structure of the IAS was designed to enable officers to cultivate and nurture this multifacetedness and it was precisely this what made IAS officers of the generation to which Ravi belonged so unique.

One of the things that stands out from Ravi’s life story is that although he came ostensibly from a family background of ‘elitist’ privilege and an upper-class lifestyle, it never impacted his ability to relate to the subaltern and the poor. For him, a career in public service was not an opportunity to acquire more privileges and concessions. It is ironic that today when the newer generation of civil servants comes from an ostensibly more ‘de-eliticised’ background, their demands for VIP perks and privileges from the very beginning of their careers dominate their attention and are seen as legitimate and normal. Ravi, like most of us in the civil services at that time, lived a life of great simplicity and innocence in comparison to what has become the norm today.

The book powerfully brings out that for fresh entrants to the IAS, the challenges then offered by a career in public service mattered more than the prospects of access to power and privilege. Idealism was then not considered naive. To be fair, impartial and to give equal respect to everyone — whatever their station in life — was a creed, a ‘dharma’, fundamental to one’s career.

Added to this was a consciousness of the fact that as a member of the only constitutionally-covenanted public service in the world, an officer owed primary loyalty to the Constitution and not to the political executive of the day. This ‘privilege’ was a vital part of an officer’s self-identity and gave him/her the determination to stand up to and resist powerful vested interests.

An incidental sidelight that the book provides is the value the civil servants of that generation (I include myself in that group) attached to command over languages and the ability to express oneself with clarity, precision and forcefulness. It is easy to see in Ravi’s book a quality he shares with many others of his generation: of being able to express himself in simple, unadorned, yet elegant, prose.

It is a pity that many of these distinctive characteristics of civil servants are now a rarity. The ‘intent to serve’ has been replaced by the intent to wield power and access privilege, constitutional conduct is subject to political expediency, language skills are distinctly poorer and esprit de corps, a forgotten value. Ravi’s memoir is a reminder of what we have lost and for that reason alone, it deserves to be read.