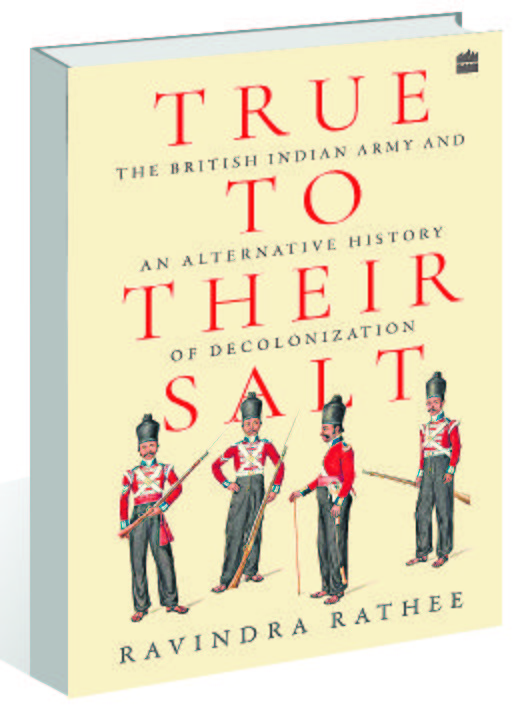

True to Their Salt: The British Indian Army and an Alternative History of Decolonisation by Ravindra Rathee. HarperCollins. Pages 380. Rs 699

Book Title: True to Their Salt: The British Indian Army and an Alternative History of Decolonisation

Author: Ravindra Rathee

Maj Gen Raj Mehta (Retd)

‘True to their Salt’ by London-based banker Ravindra Rathee is an interesting, if somewhat opinionated, book about the British empire in India and its 200-year run founded on military force provided predominantly by Indian sepoys. In the ‘Introduction’, he accepts that “the drive behind the book is deeply personal”. The book emerged from the angst his maternal grandfather underwent when, as a soldier, he was cashiered for insubordination against a British officer who had questioned INA soldiers’ loyalties at a time when tensions were running high because INA officers were being publicly tried for high treason.

Rathee opines that loyalty-imbued Indian sepoys helped install but finally demolish the Empire to whose salt they had been unflinchingly true except when their faith was trampled upon. Given the book’s intriguing sub-title: ‘The British Indian Army and an Alternative History of Decolonisation’, readers may benefit from clarity on both ‘salt’ and ‘alternative history’; these terms being open to varying interpretations, thereby opening up the Pandora’s box.

Salt has been a central aspect of ancient civilisations, including India. While being true to one’s salt implies fidelity to the employer, the relationship degrades when the employee takes his employer’s rhetoric with a “pinch” of salt. For millennia, our soldiers have followed the Naam, Namak, Nishan (Honour-Fidelity-Flag) ethic and its adjunct: Mai-Baap (firm, empathetic leadership). Rathee, using wide-ranging research, establishes that these attributes were deficient in the British; rubbing salt on their callousness/supreme indifference to their loyal sepoys’ sufferings and deaths in thousands by recalling three cataclysmic British defeats: the 1842 rout in Afghanistan, the 1916 surrender at Kut-el-Amara to the Ottoman army and the 1942 surrender to the Japanese army at Singapore. C-in-C India, Gen Claude Auchinleck, is quoted in the book as saying: “I think the English never cared... I think they used the Indian Army... They couldn’t have won the Great Wars if they hadn’t had the Indian Army.”

Clearly, the British weren’t true to their salt for the sepoy army that was the British Empire’s ‘global strategic reserve’, a bottomless resource of which future PM Lord Salisbury boasted in 1867 in the British Parliament that “we may draw any number of troops without paying for them”.

The term “alternative history” is a genre in which an author speculates with “What if?” The earliest example of alternative history is found in ancient Roman historian Livy’s ‘Ab Urbe Condita Libri’, in which Livy speculated that had Alexander the Great survived to attack Rome, he would have been defeated. Insofar as Rathee’s alternative history is concerned, one wonders what the author had in mind. Does he speculate what if the Indians had withstood the British ‘divide and rule’ (divide et impera) principle? The book makes no such speculation, making readers wonder why the subtitle was brought in, when the British edition carries no such subtitle.

The reality is that the British flogged India in every which way, including bleeding it financially. Here, Shashi Tharoor’s incisive comment, which Rathee quotes, fits: “We literally paid for our own oppression.” This amount, economist Utsa Patnaik suggests, was $45 trillion — the British siphoned it off between 1765 and 1938. Placing it into perspective, Britain’s 2018 GDP was $3 trillion.

The book follows the track of British entry into India for trade and takeover of the country using sepoys, who were paid barely above subsistence levels with far lesser pay and perks than what was given to their British counterparts. The sepoys gave them faithful service despite the deprivation, contempt and indifference routinely exhibited by the majority British rank and file. Rathee oversimplifies when he suggests that religion was behind the insurrections that erupted from time to time, of which Vellore (1806) and the 1857-58 mutiny stand out. There were complex reasons of which religion was one key factor. One would put more blame on the thoughtless leadership steeped in racial arrogance; on exceptionally poor, lop-sided man management... denying izzat (respect) and status to the unswervingly loyal sepoys — till their trust broke.

While history-writing is subjective, historiographer Rathee could’ve avoided making it personal since that muddies the book’s objectivity. This is evident from the manner in which he presents Subhas Bose and the INA’s creation and subsequent Naval mutiny as the major reasons why the British chose to “cut their losses” by departing from India in a haste, denying the humongous nationwide non-cooperation movement led by Gandhi much credit.