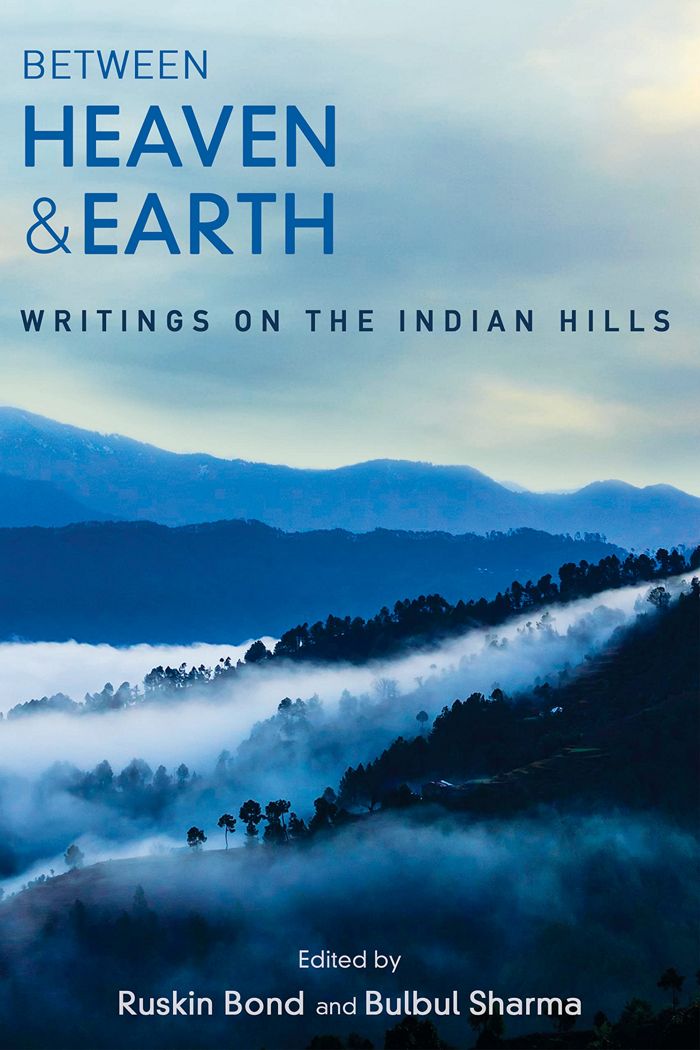

Between Heaven and Earth: Writings on the Indian Hills by Ruskin Bond, Bulbul Sharma. Speaking Tiger. Pages 432 Rs 699

Book Title: Between Heaven and Earth: Writings on the Indian Hills

Author: Ruskin Bond, Bulbul Sharma

Sarika Sharma

Indian hills had existed for eons before they were domesticated and turned into hill stations. The story that the essays in ‘Between Heaven and Earth’ piece together begins right at the beginning of this transition — with the advent of the British — and spans two centuries, recounting what was gained and lost on the way. Editors Ruskin Bond and Bulbul Sharma bring a range of non-fiction writings on the Indian hills by more than 40 writers.

Emily Eden’s letter to her sister, written in the early 19th century, which later became part of a book ‘Up the Country’, tells of a Shimla not yet the summer capital, but already a lively, colourful town. Once the chill thawed and weather opened, it was party time in the hills — dance nights, fête champêtre in Annandale, dinners, theatre, balls. She writes of how 20 years earlier, no Europeans had been there, and here they were “105 Europeans being surrounded by at least 3,000 mountaineers… wrapped up in their hill blankets…” EJ Buck’s piece, written six decades later, gives a peek into a Shimla changed by the British presence. It now had Ripon Hospital, Combermere bridge, United Services Club and a golf club.

Unaccustomed to raging summers in the Indian plains, the British would begin retiring to the nearest hills in early April. John Lang writes of the Britons calling in sick to escape the harsh weather. Men who couldn’t make it had ‘grass widows’ leading happening lives in the hill towns — from Mussoorie to the Nilgiris and Matheran. In early October, the hills would start emptying again with the thermometres dipping.

Contemporary writings included in the book engage with both the past and the present. In ‘Picturing Mountains as Hills’, an essay on the postcard culture among the British, Shashwati Talukdar writes that the earliest encounters of Europeans with the Himalayas evoked in them a particular mix of anxiety, awe and fear. Hill stations were “blank slates for reproducing an idealised version of England”.

Raaja Bhasin’s ‘Simla to Shimla: After the Raj’ throws light on the pangs the hill station felt as the British retreated and it ceased to be the Summer Capital. However, the cosmopolitanism thrust upon people was here to stay. In ‘Memories of My Shillong’, Bijoya Sawian explores the changing dynamics between the hill folk and the shopkeepers who had come to do business. From mingling comfortably, they turned against them for having taken local jobs. Parimal Bhattacharya recounts the many challenges facing Darjeeling, growing ceaselessly downwards. Siddharth Pandey’s essay is a refreshing take on the femininity of hill stations in a country brimming with toxic masculinity. Ganesh Saili’s ‘Serving Spirits’, at once melancholy, at once humourous, is an ode to all the ghost stories we grew up on. Murugeshwari, a Palaiyar Adivasi, gives an inside look into an annual forest ritual, the details of which are usually kept hidden from outsiders.

Other famous names in the anthology include Pandit Nehru, Rabindranath Tagore, Jim Corbett, Nicholas Roerich, Stephen Alter, Alka Pande, Keki Daruwalla and Pushpesh Pant. The beauty of prose and richness of detail will make for leisurely reading again and again. The only drawback are the typos that could have been avoided with just another read.