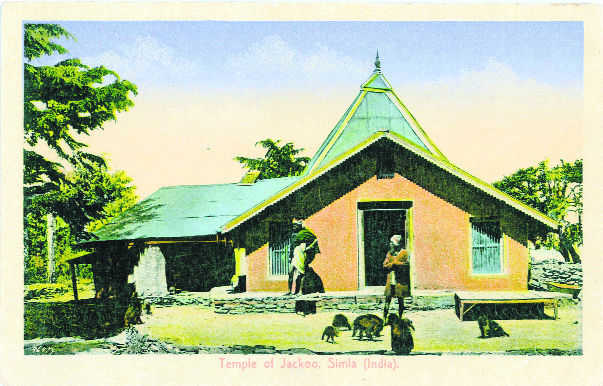

Jakhoo temple in the early 20th Century

Raaja Bhasin

Of the many unusual characters to come out of Shimla, one of the more remarkable ones was Charles William de Russet. His architect and contractor father owned a building on the town’s Ridge, when the main bazaar was located there in the 19th Century.

The father’s ‘imposing rotundity’ was reason enough for him to be remembered, when the story of the son was first written around a century ago. As often happens in tales like these, there are variations and occasionally, contradictions.

The boy Charles, studied at Shimla’s Bishop Cotton School and it is believed that it was after his father’s death that he drifted away from Christianity and “joined a fakir” at Jakhoo. Expectedly, this conversion of sorts created a minor furore. While many contemporaries glossed over it, George Ryall, Judge of Shimla’s Small Cause Court, called him and tried to reason with the 18-year-old to ‘return to his own people’. Ryall spoke kindly but ‘Charlie was determined to stick to his role’.

Russet is believed to have undergone the severe rigours of a novice for two years. He lived under a tree and the attendant who brought him food was his only human contact. He made over the property, he had inherited, to his sisters and was uncommunicative on his reasons for abandoning his former religion. John C Oman, a professor of natural science at the Government College, Lahore, met him in 1894, and recorded: “Judging from outward appearances, the man had not suffered any such physical inconveniences, as would affect his health and he was particularly well-clothed, though not in any sadhu style I have ever seen.”

A year later, Babu Balgobind, who was to retire as an oriental translator in the service of the government of India, also met Russet and that was the start of a long and admiring connection. By then, Russet was known as Baba Mast Ram. He was something of a curiosity for Shimla’s European residents and known as ‘the leopard fakir’ on account of the leopard skin he wore.

He soon came to be accepted into the priesthood and became a venerated figure. On the Baba’s death, Balgobind wrote a little booklet titled ‘The Life and Teachings of Baba Mast Ram’ and gushed: “...to know him was to love him, and to pass a few days in his holy company under the sparkling sunshine of his smiling eyes and lips, in the fragrant aroma of his saintly and celibate life was to be suffused with a subtle intoxication of exalted enthusiasm and transported into the iridescent realm of peace ineffable!”

The teachings, as they were, were simple and Russet found parallels between Jesus and Krishna and Arjuna and John. The rest of the little volume was on the 10 avatars of Bhagwan Vishnu.

In his years as a mendicant, Russet travelled to different parts of India and at Dwarka, the symbols of Bhagwan Vishnu – the discus, the conch, the club and the mace – were stamped on his arms with red-hot metal. This may have been the time, when one source mentions Russet as leaving Shimla with a band of sadhus and ‘was never heard of again’, while another declares that he began living in seclusion at a ‘temple some distance from Simla in the valley below Annandale, where he avoided recognition, shunned Europeans and seemed to have forgotten his mother tongue’.

Yet another mention in 1925 says ‘he occupied a temple in Chhota Simla’. This last, was at least a phase in Russet’s life. The story goes that when Raja Sir Daljit Singh of Kapurthala purchased Strawberry Hill just below Chhota Simla in 1921, Mast Ram occupied a room in the servants’ quarters. The Raja allowed the French fakir to stay on. An apocryphal tale is added to this, that the Raja was disgusted with the destructiveness of the monkeys and his son, Padamjit Singh, who was still a child, ‘spoke to’ Russet, who ‘persuaded’ the monkeys to stay away from Strawberry Hill – and for several years, the simian bands would sit on the boundary wall, but not enter the estate.

In June 1927, with the rare approval of the local Hindu assemblies, the Hindu hill chiefs and Hindu residents of Simla, Russet was appointed Mahant, manager and guardian of the temple dedicated to Hanuman ji at Jakhoo. He died on December 28 the same year and was cremated near the temple.

Somewhat by way of an obituary, on April 4, 1928, The Canberra Times carried a piece on Russet, where his ancestry is mentioned. Russets’s father claimed to be the grandson of the barber to the last nawab of Awadh. There was also the possibility that he was connected with a family from Northampton. This was hotly denied by the son, who said they were French. One way or another, this would make Charles de Russet the only person of European descent to have become the mahant of a Hindu temple.

(The writer is an author, historian and journalist)