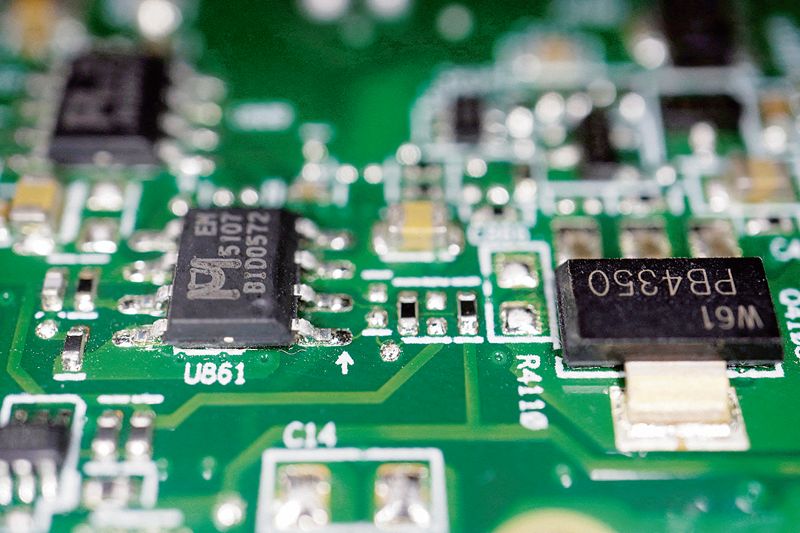

POTENTIAL: It’s possible to develop chipmaking equipment and technology independently of established producers. Reuters

TK Arun

Senior Journalist

CHINESE telecom major Huawei released a 5G capable phone, the Mate 60, on September 4. This warrants a rethink of India’s strategy to manufacture microprocessor chips. Phone companies keep coming out with new models. Why should the release of a new model by a Chinese company matter to India, particularly its ambition to become a global chip superpower?

India should have its own chipmaking capability that is not hostage to political whims of nations that control key technologies.

Huawei is not just any phone-maker. It is a company that was set up to give China indigenous capability in the entire telecom value chain, from developing communications and signalling technologies to designing chips, routers and telecom networks to producing the components that go into setting up a telecom network, besides making handsets. It spends 15-20 per cent of its turnover on R&D. It has been the world’s cheapest provider of telecom gear and rapidly gained market share around the world.

The US has banned it from its telecom infrastructure and persuaded allies to follow suit, suspecting that Huawei’s networks and equipment enable the Chinese government to snoop on the data traffic they carry. Huawei vehemently denies this, but to no avail. Under government pressure, Google withheld its Android operating system from Huawei, although not from other Chinese handset makers.

The Biden administration has tightened the tech sanctions its predecessor, the Trump administration, had imposed on Chinese companies, in a bid to prevent China from making use of American technology to race ahead of American capability in artificial intelligence and quantum computing. These technologies have strategic implications, apart from being determinants of commercial competitive advantage.

Among the sanctions has been a ban on the export of chip-making equipment and chemicals and gases to Chinese companies. ASML, a Dutch company, has a virtual monopoly over machines that make use of what is called Extreme Ultraviolet Lithography, a method of using focused laser beams to etch ultra-thin grooves on silicon chips in which to deposit vaporised copper to produce the fine circuits that go into a microprocessor. ASML follows US-dictated technology bans as its machines make use of American technology. It can export its machines only with an export licence, and such licences are not available for exports to China.

Yet, Huawei Mate 60 sports a chip with 7 nanometre circuitry, which was considered cutting-edge just a few years ago. The latest iPhone is slated to come out with a 3-nanometre chip made by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation, the world’s most advanced chipmaker. Intel, which pioneered integrated circuits, cannot today make chips this advanced.

The Huawei chip has probably been made by China’s partially state-owned Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC). The US has set up an inquiry to find out whether the SMIC made this chip with any imported equipment that violated US sanctions or on the strength of home-made R&D.

Only a few months ago, a Chinese startup successfully released a 20-nanometre chip designed and manufactured by it using homegrown technology and home-built equipment. Larger machines such as cars, refrigerators and the like make do with 20- or even 40-nanometre chips.

The chips that Vedanta was planning to make in India, drawing on liberal subsidies announced by the Central Government and augmented by state-level subsidies, were these older-generation chips. So far, no chip manufacturing company has come forward to make cutting-edge chips in the country. The US, Europe, Japan and South Korea all offer generous subsidies, running into tens of billions of dollars, for fresh chipmaking plants. Can India really compete with these countries in a subsidy race? Is it worth our while to do so? The only committed investment India has drawn in the sector is for an assembly, testing, marking and packaging (ATMP) plant, not for a fabrication unit or fab.

What the Huawei phone and the Chinese startup that came up with the 20-nanometre chip show is that it is possible to develop chipmaking equipment and technology independently of established producers. This is the track India needs to focus on, not attracting established chipmakers to set up shop in India.

Why bother with a domestic fab, after all? There could be three reasons. One is the drain on foreign exchange chips can impose. The chip import bill could well exceed the oil import bill. Another is ensuring a steady supply, avoiding the kind of disruptions that Covid-19 caused. If chips are domestically produced, the chances of their being available even when global trade is disrupted for whatever reason goes up. The third reason is to insure against denial of advanced chips on geopolitical grounds.

As America’s partner in the Quad, along with Japan and Australia, and a key counterweight to China’s overweening power in the region, India has little to fear, one would think, in terms of being denied access to crucial technology. Such thinking discounts the role of partisan spite in the working of American politics these days. A Republican or a Democratic Congress might decide to deny India access to key technology purely to spite an administration from the other party.

India has nourished strategic autonomy right from Independence and steadily sought to build up its strategic capability, even while drawing on all available arms and weapons technology on offer from different sides. In keeping with that philosophy, India should have its own chipmaking capability that is not hostage to passing political whims of nations that control key technologies.

This calls for using the allocation currently made for subsidising chipmakers to fund a range of startup companies to develop different parts of the chipmaking ecosystem. India has the engineering talent and entrepreneurial energy needed to achieve this. What has been lacking is the generous funding required to make a large number of startup bets, some of which would come good.

Let the government change tack from subsidising established foreign players to make chips in India to seeding and funding hundreds of domestic startups in India over the entire range of chipmaking tech and machines. Even if just a handful succeed, that would be enough.

Join Whatsapp Channel of The Tribune for latest updates.