CHANGE: We must be grateful to all women who spoke out about their harassment.

Flavia Agnes

Women's rights lawyer

AS soon as an issue concerning women hits the public domain, the state and civil society response is routine: "The problem has arisen because there is no adequate legal provision to address the crisis." And the demand always is for a more stringent law, widening of the definition of the crime and a time-bound trial. And before we realise, a new law is given to us, while the situation on the ground remains the same.

For instance, after the brutal gangrape and murder in Delhi in 2012, the clamour was for death penalty and fast-track courts. But the need for widening the definition has been felt for well over three decades since the amendment of 1983. Public awareness forced the government to set up the Justice Verma Committee and based on it came the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 2013 which was much needed. And fortunately, the demand for death penalty was not heeded due to objection from women's groups. The situation on the ground continued without much change.

Next, we were confronted with the brutal gangrape and murder of an 8-year-old child in Kathua. Here the issue had a political angle; it was not just rape. It was hatred against a nomadic Muslim tribe, the aim being to scare them away from the area. But to contain the protest without addressing the underlying political concerns, the Protection of Children Against Sexual Offences Act of 2012 was amended to bring in death penalty for rape of children under 12 years.

Death for outsiders

But as statistics reveal, most rapes are committed by persons known to the victim. So how will death penalty be a deterrent? There are more chances of the child and her mother being declared liars and manipulators in a hostile court environment. Only in cases of rapes by strangers and, more particularly, those committed by "outsiders" — outside the caste, community and religion — that they are selected for death penalty.

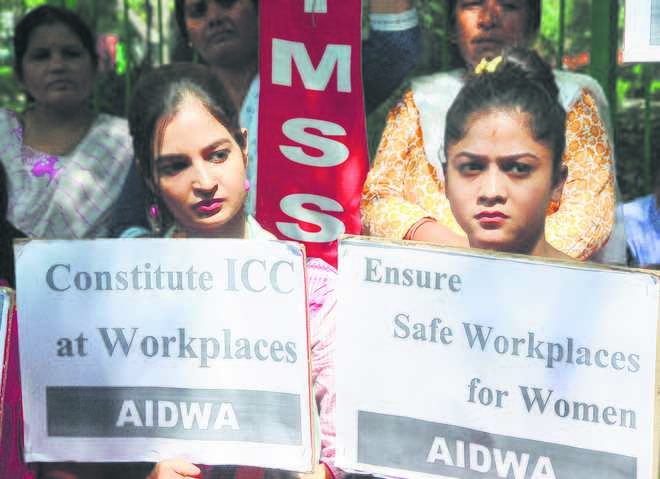

Now the #MeToo campaign has laid bare the inadequacies of the Sexual Harassment at Workplace Act of 2013. To begin with, there are many, as pointed out in articles by Justice Sujata Manohar, retired Supreme Court judge who was part of the Bench along with Justice Verma which laid down the Vishaka Guidelines way back in 1997, which was the foundation upon which the SH Act was formulated. She and Justice G. Rohini, retired Chief Justice of the Delhi High Court, pointed out these lacunae at a recent consultation meet called by the National Commission for Women.

The NGO representatives at the meet — mainly from Delhi and a few from elsewhere — pointed out that the Act had been a non-starter because the Local Complaints Committees which are meant to address two important segments have not been set up or where they have been set up, they exist only in name. The parody is that these government officials have to address complaints from two different and diverse segments of society: one, complaints from women in the unorganised sector: the illiterate, low paid woman who works without any job security; and at the second level, complaints against the head of an organisation (for example a Tarun Tejpal or an MJ Akbar who are armed with a battery of lawyers) who have scant respect for the members of the Local Complaints Committee.

The NCW chairperson, Rekha Sharma, who presided over the meeting, admitted that even internal complaints committees do not work as the perpetrator may be a highly placed official and the committee constituted by the head of the organisation would be his support base. In such a situation, the requirement of appointing an external NGO member does not have much impact unless she is able to influence the committee members. But if she too harbours the same conservative values and sexist biases, the complainant has no hope of getting justice. Her only option is to file a criminal complaint with the police, which also may not take her far and she would be so bogged down by the criminal procedure that she would withdraw her complaint.

Further, the Act deals only with a situation where the complainant and perpetrator work in the same organisation. If they have moved, there is no remedy. There is also a time limit of three months for filing the complaint. So, the women who came out in social media had no remedy in law except to file a police complaint. It is for this reason that the Act was a non-starter.

So, this is the answer to the oft raised question of why she didn't complain earlier and why she was complaining now.

On the positive side, the #MeToo campaign has shaken the corporate world in a way the 2013 Act and the Vishaka guidelines could not do and has helped focus on the situation that prevails. The stories were shocking. But more importantly, it became obvious that the current law has no remedy for them. This has forced the government to sit up and take notice.

A suggestion made by Justice Manohar and endorsed by many at the meeting was to set up industry-wise committees, such as the film industry, the media, the financial firms etc, which the woman can approach if she is not comfortable about filing a complaint in her own organisation. This will also address the problem of harassment by the head of the organisation and also deal with small and medium level firms within a particular sector.

Sexism at workplace

Another suggestion that came up was to broaden the definition of "sexual harassment" to include gender discrimination and sexism at the workplace. Many times, women are discriminated against because of sexism that prevails at the workplace though there may not be a "sexual" motive involved. But they have no remedy under the prevailing law. But this would involve many more issues which the internal committee may not be equipped to deal with and it would need special training on the issue of sexism at the workplace.

Penalising the complainant

The other suggestions were to delete the clause which penalises the complainant if she is not able to prove her allegation on the ground that it is a false case. This prevents many women from approaching the committees. Also, at present, the committee can only make recommendations and it is up to the employer to implement them. There must be an appellate body to take the employer to task and penalty should be prescribed for non-implementation of recommendations.

Now it remains to be seen which of these recommendations the government will accede to. But we must be grateful to the #MeToo campaign and to all the women who spoke out about their harassment for starting this process of amending the law.