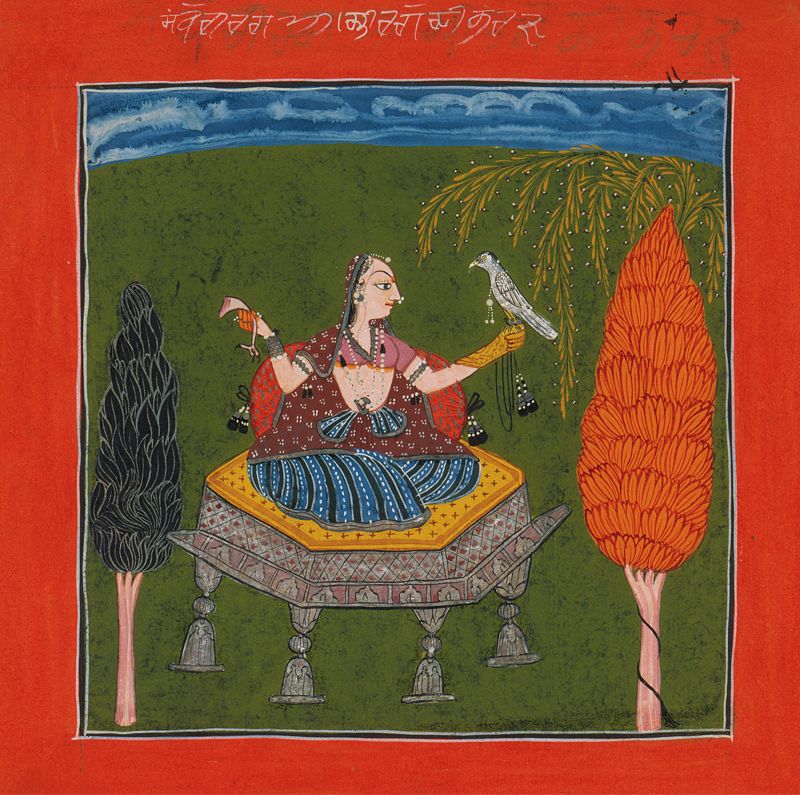

Folio from a Ramayana series (ca. 1690-1710). Even as the precise school or atelier remains elusive, this folio from a dispersed manuscript of 50 leaves is attributed to the hill schools of northern India on the basis of the ink annotations in Takri script. Photo courtesy: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Sarika Sharma

WHAT use is a near-extinct script? Ask a gallerist in the United States or United Kingdom, and you will know. Over the years, as the art world has come to be in awe of Pahari painters, led by Nainsukh of Guler from the erstwhile Punjab hills, a forgotten script has become a definitive tool to mark the artworks as Pahari. Once the script of royal courts and the business community, Takri (also known as Tankari) fell out of favour with the increased use of Devanagari and Urdu, and simply faded away.

Decades later, efforts are being made to save whatever remains of the script that once defined what the varied languages of present-day Himachal Pradesh expressed — from Lahaul-Spiti to Kullu, from Mandi to Kangra, Sirmaur to Chamba, and beyond.

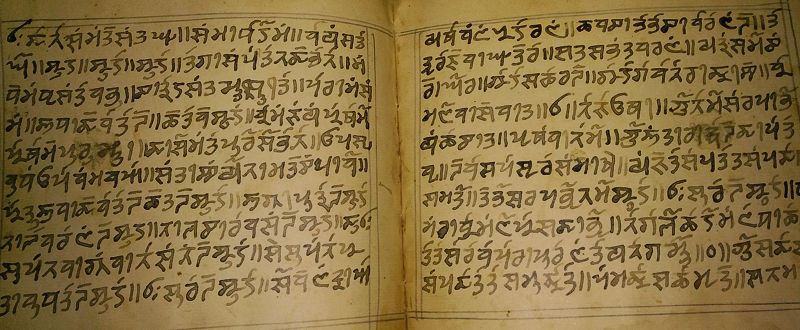

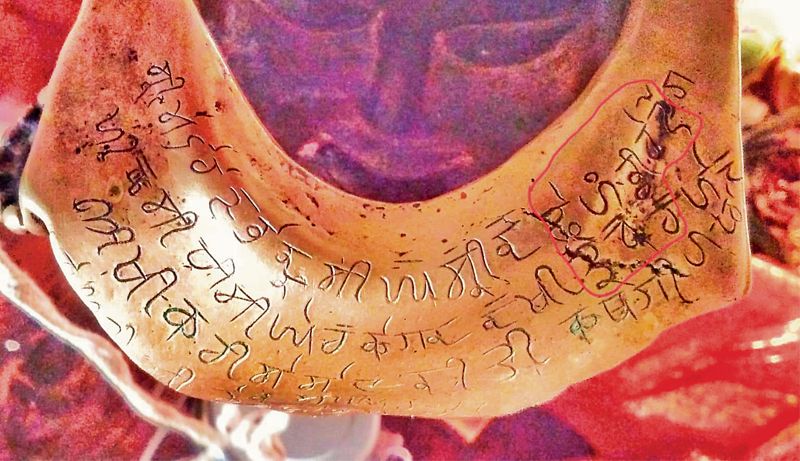

Derived from Sharda script of Kashmir, Takri came to the Punjab hills in the 13th century. For a layman, the inscriptions on temples dotting the hills would be the most obvious testimony to the lost language. But researchers often find themselves peering into the account ledgers of temples, land revenue records, royal correspondence, some translation works, Pahari paintings… Loss of the script has meant the knowledge of the indigenous medicine system, literature and philosophy has been lost too.

But it wasn’t so until a hundred years ago, when Takri was one of the main scripts, as confirmed by Sir George Abraham Grierson in his 1916 Linguistic Survey of India: “All over the Western Pahari area, the written character is some form or other of the Takri alphabet, but the Nagari and Persian characters are also used by the educated.”

The attempts to integrate the country pre-Independence (by the British) and after Independence, in a way, spelt doom for the script. Increased correspondence with the outside world meant increased use of Urdu and Devanagari, which were already mediums of instruction at schools.

Post the creation of Himachal in 1971, not much was done to introduce it to the school curriculum or give it the status of a state script, unlike Gurmukhi in neighbouring Punjab or Dogri in Jammu (both derivatives of Sharda). Linguist Ganesh Devy says that the writing technology had changed in those times. “Unlike Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, West Bengal, Odisha, Maharashtra and Gujarat, Himachal was not created entirely as a linguistic state. It had other complex features — ecological, sociological, historical. And, therefore, not surprisingly, ‘script’ was not a primary focus of the then government.”

Post the creation of Himachal in 1971, not much was done to introduce it to the school curriculum or give it the status of a state script, unlike Gurmukhi in neighbouring Punjab or Dogri in Jammu (both derivatives of Sharda). Linguist Ganesh Devy says that the writing technology had changed in those times. “Unlike Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, West Bengal, Odisha, Maharashtra and Gujarat, Himachal was not created entirely as a linguistic state. It had other complex features — ecological, sociological, historical. And, therefore, not surprisingly, ‘script’ was not a primary focus of the then government.”

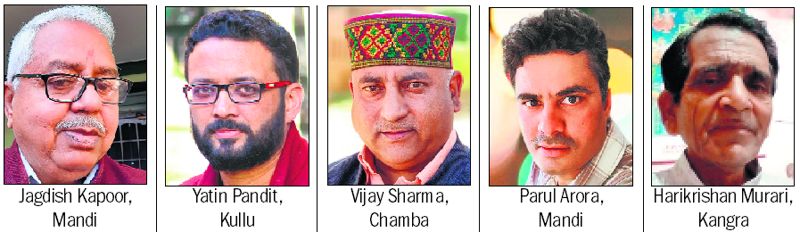

Takri rapidly became a script for only old-timers to follow, some of whom were using it until the 1970s, according to scholar Jagdish Kapoor from Mandi. He remembers people signing in Takri when he joined the banking service in the 1970s, but saw it fade away eventually. His interest in the script was kindled when he found his grandfather’s account ledger in Takri and started learning the script.

Over the last few years, Yatin Pandit, a researcher from Kullu, has translated several account ledgers of local temples. “Some as recent as the 1930s and 1940s,” he says. A history buff, this 39-year-old came across several references to the script in books by British scholars and, in 2016, began learning Takri. He learnt to use the font developed by Sambh, a Kangra-based organisation that works towards the preservation of Himachali heritage. Over the last few years, he has been giving classes on Takri and working on developing a primer for Kullui Takri, along with the shapes alphabets took, while looking into the possibilities of why it must have happened.

From 60-year-old Padma Shri awardee painter Vijay Sharma to 36-year-old Parul Arora, Takri has found its ardent fans who are trying to learn the alphabet and share their knowledge. While Sharma has been teaching at the Bhuri Singh Museum in Chamba and helping international museums such as the Metropolitan Museum in USA and auction houses like Sotheby’s in deciphering Takri inscriptions on Pahari paintings, Arora runs a small Takri school sponsored by the Himachal Pradesh Academy of Arts, Culture and Languages in Mandi. His five students come from varied backgrounds. One is an author, another a journalist; there is a teacher, a private sector employee and a social worker. Arora says he was drawn towards the script full-fledged after he lost his job during the lockdown. Pained to see his fellow Takri lover from Mandi, Jagdish Kapoor, not get his due for all the efforts towards the script, he arranged to put up a stall of his book at Mandi Shivratri earlier this year, where more than 100 copies were sold.

A major find in his journey to discover Takri has been a book, ‘Varnmala Takri’, by Bakshi Ram, written during the reign of Raja Vijaysen of Mandi in the 19th century. “The book is the best one could have asked for learning a script. It has swar, vyanjan, matrayein, framing sentences, writing letters, even tables in Takri. This book is testimony to the fact that this was a full-fledged script, multiplication tables indicate that it was perhaps taught in schools too. We have found a base to work on!”

While a lot of young researchers are giving Takri the much-needed fillip, it has survived the test of time because of the likes of Jagdish Kapoor, poet Harikrishan Murari from Kangra, the late Dr Rita Sharma from Chamba and the late Khubram Khushdil from Kullu. While Murari has trained most young Takri enthusiasts in the state and elsewhere, Khushdil, a nonagenarian who passed away last year, is hailed as the man who collected the most Takri documents over the last century. Historian Tobdan says it is to Khushdil’s credit that he worked towards preserving a script the state and people had turned away from. All his life, he collected and translated Takri documents from Mandi, Kullu and Lahaul, among them a huge pile discovered beneath a statue at the Murlidhar temple near the historic Chehni Kothi in Banjar tehsil of Kullu district.

“The problem with the survival of Takri is that a majority of the available documents are on subjects (tantra-mantra, revenue records, etc) serious scholars are not much interested in,” says Tobdan. However, he feels that Khushdil’s vast collection needs to be preserved and shared with scholars.

Himal Nachiketa Das, a documentary filmmaker, profiled Khushdil towards the fag end of his life in his film, ‘Tankari’. He says thousands of documents are lying at Khushdil’s place and it would be apt to preserve them before they decay with time. He has also photocopied around 5,000 of them for the Bhasha Academy. A museum at Dev Sadan in Kullu has a handful on display.

Arvind Sharma, convener of Sambh, says what worked in favour of Gurmukhi was that Guru Granth Sahib was written in it. Eventually, this was followed by various literary writings. Devy says this couldn’t have happened with Takri because this script was serving a different purpose.

“When we look at the writing systems in India during the 13th and the 14th centuries, it is necessary to recall that paper trade had arrived in India around this time and was flourishing. It is important to note that paper was being used for writing related to ‘record keeping’. As a result, various short-hand writing systems evolved around this phase in various parts of the country. For instance, the ‘Modi’ script in Western India was used in regions that are now known as Gujarat, Maharashtra and Karnataka,” says Devy.

These were not fully new scripts, but new formulations of existing scripts, in which joining letters or moving from one character to another was made relatively easy. Takri, the script that replaced Sharda, was one such. “Given the nature of its use, it spread across vast areas through the networks of ‘commodity-exchange guilds’ (merchants, for example). Sharda, the earlier script, was — as against Takri — used for writing genealogies, poetry and philosophical treatises. It was a script primarily used by the ‘literary’ class. In the subsequent centuries, Takri found a place among small hill kingdoms as it could be grasped easily by the ruling elite. And since they had accepted Takri, the literary class too adopted it. The fortunes of scripts such as Takri declined with the induction of the print technology for Indian languages,” says Devy.

But hope floats among those taking pains to learn and teach the script: in Yatin Pandit, who runs a daily needs store in the day and turns history buff by night; in Parul Arora, who has found new meaning in life post losing his job during the pandemic; in Harikrishan Murari, who is now attempting a literary work in Takri. Perhaps together they would be able to recover what is not yet entirely lost.

Emergence of a distinct script

It is believed that when Kashmiri Pandits came to Punjab hills along with the traders, they brought with them the Sharda script — a writing system for Kashmiri language, which originated in the 8th century and was in use in Kashmir till the 13th century. As time went by, it took on various forms and became Kullui, Mandeali, Sirmauri, Chambeali, Jaunsari, each slightly different from the other. According to Omniglot, an online encyclopaedia of writing systems and languages, Takri emerged as a distinct script during the 16th century. “Takri was an official script in parts of north and northwest India from the 17th century until the mid-20th century. In Chamba, as Grierson noted, the script had been “advanced to the dignity of the printing press, and type in an improved Takri has been cast”.

Sir George Abraham Grierson on Takri

“The name of the Takri alphabet is most probably derived from Takka, the name of a powerful tribe which once ruled this part of the country, and whose capital was the famous Sakala, lately identified by Dr Fleet with the modern Sialkot. The Takri or Takkari alphabet is closely connected with the Sarada alphabet of Kashmir, and with the Landa, or ‘clipped’, alphabet current in the Panjab and Sind. It is built on the same lines as Nagari, but the representation of the vowels is … most imperfect. Medial short vowels are frequently omitted, and medial long vowels are often employed in their initial form.”

Source: Linguistic Survey of India, 1916

Join Whatsapp Channel of The Tribune for latest updates.