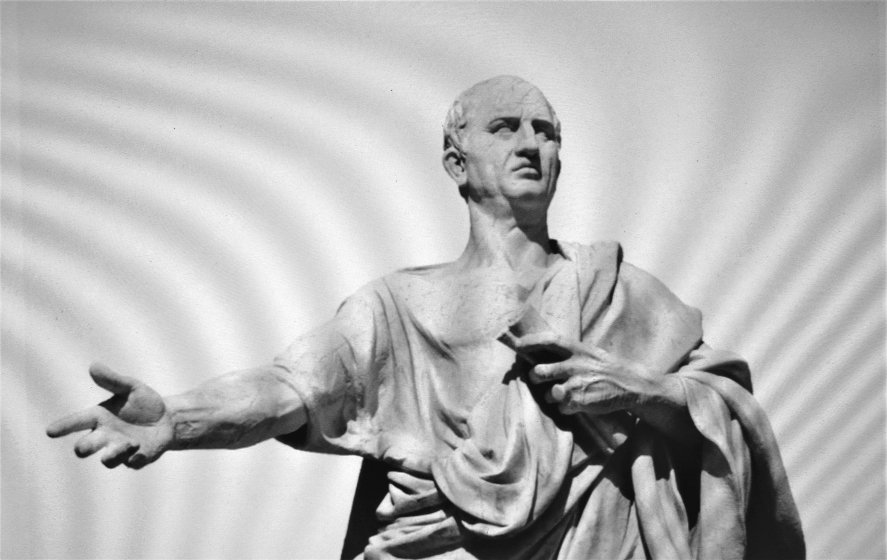

Gaius Gracchus addressing a crowd of plebeians, an artist’s impression

BN Goswamy

The evil that men do lives after them;

The good is oft interred with their bones;

So let it be with Caesar…

But Brutus says he was ambitious;

And Brutus is an honourable man.

He hath brought many captives home to Rome

Whose ransoms did the general coffers fill:

Did this in Caesar seem ambitious?

— Excerpt from Mark Antony’s speech in Shakespeare’s ‘Julius Caesar’

It might have been these words — laced as they are with incomparable irony and eloquence and rage — that were ringing in my ears when I picked up, from the college library, Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s book, ‘Rienzi, the Last of the Roman Tribunes’, without knowing much about it. This must have been a very long time ago, when I was studying in my ‘intermediate’, as it used to be called then. The name of Rome and of a man speaking up for the people were enough to attract me to it. It was an absorbing story, it so turned out, tracing the career of a man who established in medieval Rome yet another Republic in the 14th century: a man vastly popular once, but then betrayed, excommunicated, and assassinated. Soon afterwards, however, the tribunes went out of my mind, except when I heard of an opera by Wagner on the same Rienzi years back in Germany, but most recently, when I was kindly asked to write a piece for The Tribune in our own city in connection with the 140th anniversary of the founding of the newspaper. With that, I was back with the ‘tribunes’ of the past, and decided to learn a bit more about them.

There was a great deal to learn, I found, for one really knew nothing to begin with. But it was enriching, and, intriguingly, still relevant in many ways. The word seems to have stood originally for an officer connected with a tribe (tribus), or who represented a tribe for certain purposes. In ancient times, there were different tribes that made up as it were Rome, and the tribes needed to be represented, especially when the monarchy was thrown out in 509 BC, and a republic established which lasted till 27 BC, when Empire replaced Republic. In the Republic, to put it in the broadest of terms, there were two groups — classes in fact — which often found themselves opposed to each other: the patricians and the plebeians. In other words, the nobility and the peasantry, the ‘haves’ and the ‘have-nots’. But, knowing that they could not run the state, or even exist, on their own, the patricians, by common consent, recognised the plebeians and invested officers elected from among them with powers. This was a recognition of the wisdom contained in the folkish fable of ‘The belly and the limbs’: that one could not survive without the other. These elected officers, called the tribuni plebis, were granted not only the right of convoking meetings of their tribes, but also the duty of defending the privileges, some old and some new, conferred on them. There were other tribunes — those representing the military, for instance — but the tribuni plebis were the first offices of the Roman state that were open to the plebeians, and were, throughout the history of the Republic, the most important check on the power of the Roman Senate and magistrates. For, by law, they could summon the Senate, propose legislation, and intervene on behalf of plebeians in legal matters. The most significant power in their hands, however, was to veto the actions of the consuls and other magistrates, thus protecting the interests of the plebeians. The tribunes of the plebs were sacrosanct, meaning that any assault on their person was punishable by death. All the same, the interests of the two classes being very different, there were clashes: violent clashes, sometimes. Whatever protection the law granted to the tribunes, it was not adequate against ‘the insatiable ambition and usurpations of the patricians’, as a contemporary historian put it.

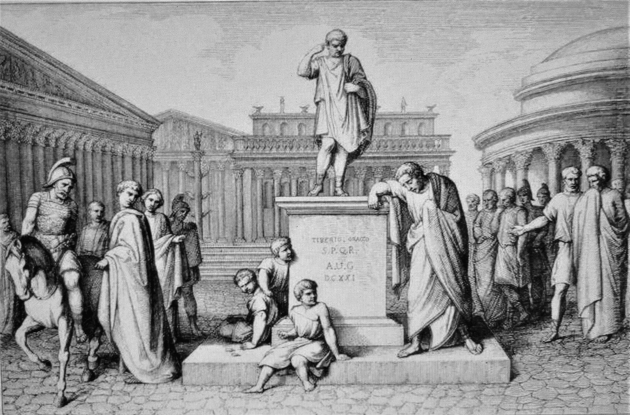

Over a long period of time, there were hundreds of tribunes who came and went, each having had to put up with, and manage, the challenges of his time. But perhaps the most celebrated names that have come down are of the Gracchi brothers: Tiberius the older, and Gaius the younger. Recognising that there was tremendous imbalance of wealth in the Roman Republic, Tiberius (163-133 BCE), when elected, fought for distributing land to the workers proposing that no one would be allowed to hold more than 500 iugera (about 125 acres), and anything in excess would be redistributed among the poor. The wealthy landowners were not pleased. A violent encounter took place in the Senate, and Tiberius was beaten to death. With time, Gaius filled the position left by the death of his older brother. He created a coalition of poor free men to follow him and when, one year, locusts and drought brought Rome to its knees, Gaius enacted a law providing for the construction of state granaries and for the regular sale or dole of grains to the powerless and the hungry. Displeased with all this, the Senate passed a decree that declared Gaius an ‘enemy of the state’. Since there was going to be no trial, Gaius knew what awaited him, and committed suicide. There is a footnote that historians add to these episodes. “After the death of the Gracchi brothers, major disturbances broke out in Rome. People still worship them and made statues of them around Rome.” The need to speak up was never abandoned.

My father used to tell us how, in our land in early times, kings always used to have a mentor, a Rajguru so to speak, seated by their side, with the right and the duty to tell him if and where he was going wrong. “Rajan! Aapke rajya mein yeh anyaaya ho raha hai,” the Rajguru would say, aloud. After telling us of this ancient practice, he would point to one of my two sisters, and say that this is what she is meant to do at home!

Join Whatsapp Channel of The Tribune for latest updates.