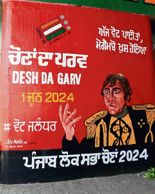

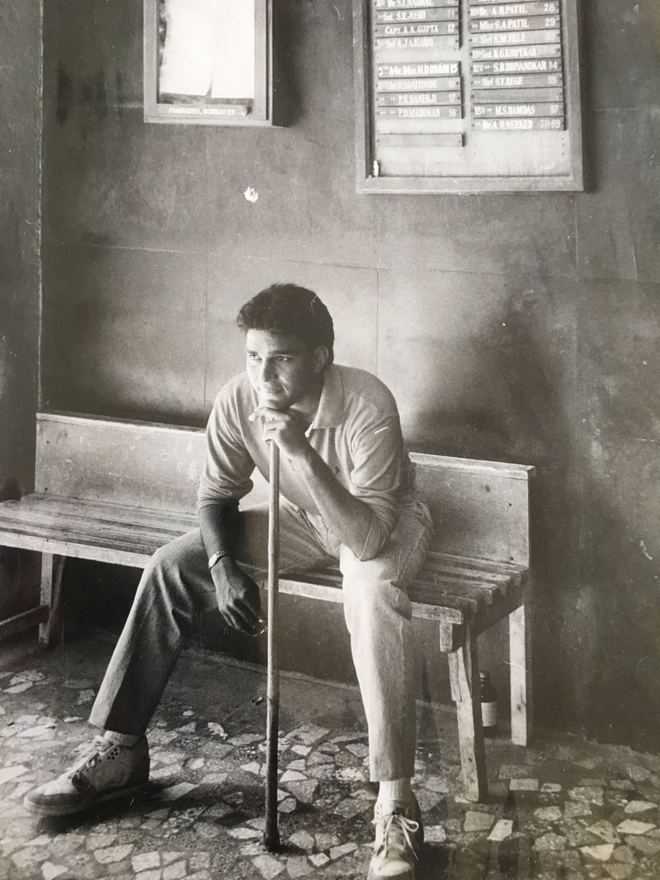

The naked truth: In this bare-all book, Sanjay Manjrekar analyses his life, his rise and fall from grace with a dispassionate, clinical precision photo courtesy: harper

Rohit Mahajan

As a child, Sanjay Manjrekar would rush to close the windows when his father, a man with great cricket talent and greater temper, would get angry and had a “showdown” with his family. Sometimes these showdowns “even got violent”. Manjrekar and his sisters closed the windows because they didn’t want the neighbours to hear the sounds of the terrible clashes.

That’s how families behave — hiding the shame is considered the prudent thing. Manjrekar, through this book, demonstrates that to him, in his endeavour to tell the story of his life, truth matters more than a false sense of honour.

Manjrekar wishes to set the record straight, and he manages to do that in this slim book which is more truthful than tomes produced by other Indian cricketers.

Over the years, when Manjrekar raised questions about the decline of Sachin Tendulkar and MS Dhoni, people imputed motives to him. But it’s more likely that he was just telling it as he saw it; this book shows that’s the sort of man Manjrekar is. He does it to himself, too, laying bare his worst traits as a cricketer and, even more creditably, as a human being.

His very difficult, fearful childhood shaped his mind and, he surmises, his mindset possibly made him a very defensive batsman. His father, the great Vijay Manjrekar, rarely watched him play and the two had “no relationship to speak of”. “The overpowering emotion that I feel towards him was fear,” he says. But from his father he also got the confidence that he, Sanjay, too could become an India cricketer.

Dark side of cricket

We know that only one in a billion becomes Sachin Tendulkar or Virat Kohli. What happens to the millions of other boys who dream of cricket stardom — what happens to the sport’s detritus? What goes through the mind of a cricketer when he fails and fails, and sees a lifetime’s hard work go up in smoke? Manjrekar has documented all this — how his career went to pieces, and with it his peace of mind — in this remarkable book.

He also takes you on a trip to the dressing room — the groupism in the Indian team, the gutsiness of men such as Manoj Prabhakar and Kiran More, the uninspiring captaincy of Azharuddin, the Kapil Dev who is now a “sweet, humble and amiable” man but was “nothing like that as a player”.

The most heartwarming parts of the book comprise his exchanges with the kind and wonderful cricketers from the West Indies, such as Desmond Haynes, Jeff Dujon and Malcolm Marshall; and also Imran Khan’s deep concern for his batting and Maninder Singh’s bowling.

Mind games

Manjrekar, a cerebral man with great clarity of thought and expression, shows how failure, fear and doubt prey on the mind of a sportsperson; how confidence erodes and then disappears completely; how a sport that was full of joy becomes a horrible torment that affects the mind and puts strains on relationships.

Manjrekar was a great talent — men such as Viv Richards and Imran Khan sought him out to compliment him. Malcolm Marshall and Ian Chappell discussed his batting with him. In 1989, he was the Next Big Thing of world cricket. He was a superstar in the making. But Manjrekar had a fatal flaw — two fatal flaws, in fact: arrogance and an obsessive nature.

He doesn’t spare himself as he relates how success went to his head. “During this phase people close to me also saw me get a bit cocky, not necessary on the field but off it. I would throw tantrums if things didn’t go as per plan,” he writes. “I also enjoyed making others look small by exposing their weaknesses.” He did it to even Mohammad Azharuddin, then India captain, in a “non-descript company match”.

Then came the failures, most significantly in Australia in 1991-92. He started blaming his teammates. “Often, I would blame those batting with me for my dismissal, especially in run-out situations. I would call them names to let off steam.”

Tinkering with technique

His obsessive, nerdy nature kicked in. He began to react to advice and suggestions from players and coaches. He got too much advice, and he tried most of it. “I was making very subtle changes almost every day,” he writes.

That way lay disaster, and disaster did strike. Dropped and sent off to play the Ranji Trophy, he was angry and frustrated as an “India discard”. As captain, he began to behave very badly. His teammates thought he was a tyrant. Once he repeatedly needled an umpire after an argument and was sent off the field.

Manjrekar, a rationalist and atheist — he says he has “no time for religion” as “it is an outdated concept” — tried to solve his problems with reason and training alone. Excessive thought and tinkering proved detrimental. A simpler teammate, Azharuddin, would leave it all to “Him” (God) and merely “threw my bat around”. But the complexity of Manjrekar’s mind is in sharp contrast to the mind of Azharuddin or Virender Sehwag. Manjrekar sunk into the morass of over-analysis of technique.

The end

An article about him said: “Sanjay Manjrekar’s game is going from one weakness to another.” Manjrekar completely agreed with this view. Strangely for a rationalist and atheist, he became a fatalist. After yet another failure, he “began to tell myself that perhaps it was not meant to be”.

He realised his troubles lay in his mind. “My problems were deeper. How could a biomechanics expert change the person I was? There is a Marathi saying: ‘Swabhavala aushad nahi.’ There is no medicine for nature.”

So, there was no cure for Manjrekar’s tormented mind. He retired at age 32 because he was too tired of “swimming against the tide”. Thus ended the career of the man once hailed as the next Sunil Gavaskar.