Ratna Raman

Diwali is celebrated all over northern India recalling Rama’s homecoming to Ayodhya. Everyone fixes their own homes, makes rangolis and lights lamps, dropping off sweets and gifts to families and friends, while rejoicing over the arrival of the mythic king. Onam in Kerala elicits this sort of response for more than a fortnight, although the celebrations are for honouring the Mahabali.

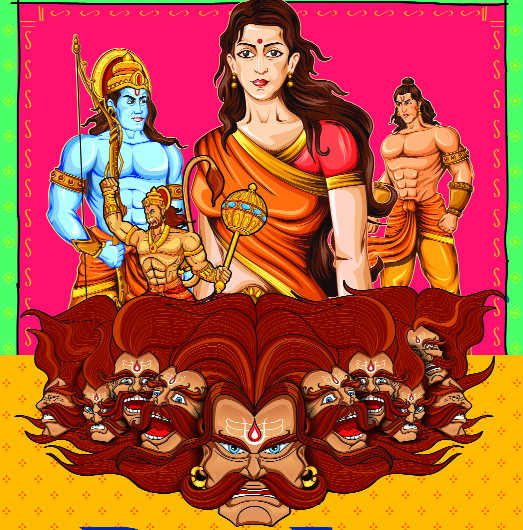

Rama returns home, along with his wife Sita, brother Lakshman and a retinue of followers. Sita’s arrival is celebrated as the visitation of Goddess Laxmi, the good-natured goddess, and there is boisterous gambling, with playing cards instead of the proverbial dice, amid feasting and firecrackers.

This mythic celebration mimics conjugal successes in happy households: the roles of women and men, follow older traditional patterns, although now Diwali’s ante has been raised through conspicuous consumption in affluent households.

In South India, Diwali is celebrated a day earlier and the sequence of rituals is very different. Most celebrations finish early in the morning around a ritual bath and firecrackers after which families feast with traditional sweets and savouries. There is no Laxmi Puja in homes.

Laxmi Puja, wherein only Goddess Laxmi is summoned and prayed to, happens on a Friday in August. In South India, Diwali is a celebratory moment because yet another demon Narakasura has been vanquished at the end of a joint venture by Krishna and Satyabama. This mythical event was recorded as happening on the eve preceding Diwali. Narakasura had imprisoned 16,000 women and had also humiliated the mother of the gods, Aditi. Narakasura’s vanquishment is a woman-friendly narrative. It is structured around the release of the women from Aditi’s household. Aditi herself is the wife of sage Kashyap, the eternal mother figure from whom all devas originated. The defeat of evil is celebrated by the lighting of diyas.

In South India, Vishnu commands deep reverence. While Rama has enough temples to his name, he is subject to occasional irreverence and is seen as everyman. The expression ‘Saapaatu Raman’ is a term used for gluttons, too fond of food, while the expression “Kothanda Raman,” an epithet for the martial god with bow and art describes an aggressive, bad-tempered, man. “Kalyana Raman,” describing the married householder is, perhaps, the more pleasant of the name callings, although this aspect of Rama as a decent husband is now contested by feminists because Rama does treat Sita rather shabbily on more than one occasion.

Irawati Karve terms Sita’s forest sojourn as idyllic. This is incorrect because the forest is invariably more rugged and demanding of everyday lives than the luxurious world of the court. Here, Sita is kidnapped and intimidated by Ravana and a huge battle ensues before Ravana can be routed and killed.

Sita’s agni pariksha becomes a test of her unsullied chastity, after which, she is brought back home.

All bodes well in Ayodhya, until the washerman’s refusal to accept his wife’s return home declaring that he is not a Rama who will condone her infidelity, is brought to Rama’s knowledge. The taunt rankles. Choosing to reign by example, Rama banishes a pregnant Sita to the forest. Rama’s response is outrageous and finds little justification in the hearts and minds of innumerable readers of the Ramayana, who provide their own versions of Sita’s stories.

Even, Bollywood which can lapse into stereotypic representations of women at any given opportunity offers a wonderful song wherein the hero tells his beloved that he will not ask her about her past and what she did: “Mujhe nahi poochni tumsey beeti baatein.”

He asks for fidelity and commitment from that particular day (aaj se) and goes on to explain his position by accepting; ‘Mai Ram nahi hoon phir kyoon, ummeed karoon Sita ki’. Unfortunately, this egalitarian stance has made little impact upon patriarchal perspectives that continue to subject hapless women to stringent codes of behaviour.

Nevertheless, it is pertinent to recall that Sita is not a passive victim of circumstances. After Rama claims her sons, (despite zero parenting) and informs her that she must prove her virtue yet again, Sita directs her pleas to mother earth and wishes to be reclaimed by her. She is very clear about not wanting to go back to Ayodhya as a twice-resurrected wife. The earth opens and she is absorbed alongside its many untold secrets. This quiet assertion that Sita’s dignified resistance sets up touches a chord in innumerable hearts. That Sita is no pushover continues to be iterated by innumerable retellings of her story in a multiplicity of languages.

A.K.Ramanujan’s brilliant essay Three Hundred Ramayanas draws our attention to versions wherein Sita features as Ravana’s daughter and has a discussion with Surpanakha’s daughter about Ravana. The version positioning Sita as Ravana’s daughter is an important fable for our times. The ugly reality wherein fathers molest daughters is lent greater credence by the myth which spells out the generic vulnerability of daughters. This homegrown myth should have greater resonance worldwide when pitted against the Electra complex (Freud’s guilt-inducing assertion of how daughters remain dubiously attracted to their fathers). More daughters have suffered worldwide under the grim authority of patriarchs than fathers who have been loved and obeyed by daughters.

The maiming of Surpanakha provides yet another pointer to the punitive treatment meted out to women in modern times. I often asked myself why a woman persistently wooing a man should have her nose and ears cut off only to discover that khaps sanction the killing of women who choose to love without sanction. Modern instances of rejected suitors stabbing women to death or hurling corrosive acid in their face are possibly vestiges of punitive patriarchal authority drawn from more ancient times.

Sita’s grace under pressure, Satyabama’s collaborative effort and Surpanakha’s spirited enthusiasm are symbolic assertions of strength and represent extraordinary possibilities for our times.Their stories are life lessons that continue to highlight for women the world of predatory fathers, domineering husbands and hostile males.