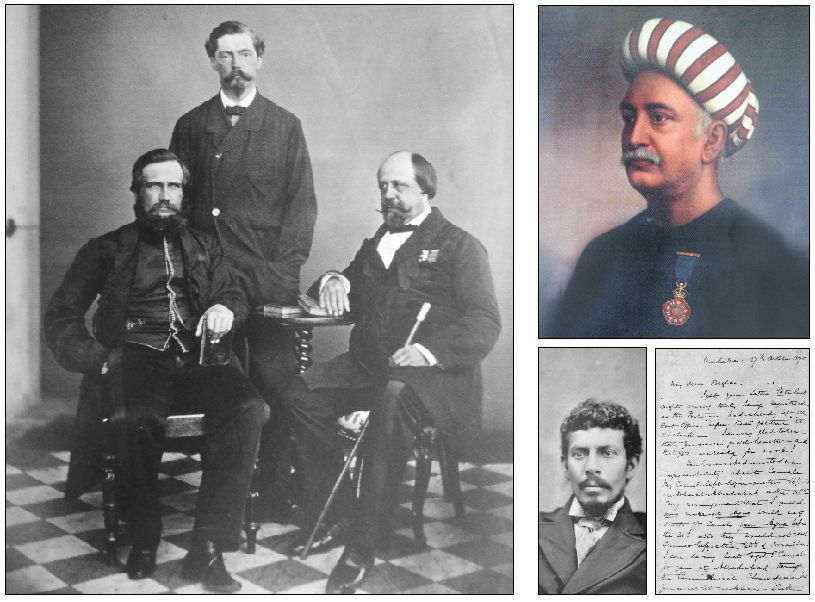

(Clockwise from far left): Alexander Cunningham (R, sitting) with two officers from Bengal Engineers; Rajendra Lal Mitra, among the first Indian cultural scholars writing in English: a contemporary of Alexander Cunningham; a letter written by Cunningham to Beglar in 1878 from ‘Umballa’; and a portrait of James Beglar, Cunningham’s assistant.

BN Goswamy

I believe that the duty of investigation, describing, and protecting the ancient monuments of a country is one that is recognised and acted on by every civilised nation in the world. India has done less in this direction than almost any other nation … I am strongly of the opinion that immediate steps should be taken for the creation under the Government of India of a machinery for discharging a duty, at once so obvious and so interesting.

Lord Mayo, Viceroy of India, 1870

What the learned world demands of us in India is to be quite certain of our data, to place the monumental record before them exactly as it now exists, to interpret it faithfully and literally.

James Prinsep, English scholar and antiquarian. ca.1835

IT is from the welter of words and thoughts, of the kind cited above, that sprang one of the great organisations — Surveys was the term then most current — which the British founded in the 19th century in India. And a central figure in these developments was an intrepid man whose world historian Upinder Singh has explored in an utterly absorbing work — rich in facts and numbers but remarkably accessible — that she has just published. Alexander Cunningham (1814-1893) was the man — younger brother of Joseph Davey Cunningham, whose pioneering work, ‘A History of the Sikhs’, we in the Punjab might be more familiar with: soldier, engineer, demarcator of international boundaries, surveyor of river courses, but, above all, one in love with antiquity. And the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), now a hundred and fifty years old, was the institution.

Alexander Cunningham did not start as an archaeologist; having arrived in India in 1831 and having been commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the Bengal Engineers, he stayed in our land for something like 46 years during which his duties kept varying and expanding. He served as aide-de-camp to the Governor-General, Lord Auckland, built bridges as an executive engineer, participated in the East India Company’s military campaigns, including the second Anglo-Sikh war in the Punjab, was dispatched on diplomatic missions to negotiate boundaries.

It is as if he was versatile enough to fit into any role, but the one he seemed to have enjoyed most, during his tenure with the army, was as an Executive Engineer of Gwalior state in 1851 when he got the opportunity to explore Buddhist stupas in and around Sanchi. He was, at heart, an ‘antiquarian’, interested in everything ancient, from studying sites to gathering coins, looking at temples as much as at ‘the stone and timber of the Gwalior region’. In 1861, he retired from the army with the rank of Major General, but not before he had travelled extensively throughout the land, and having seen with a sharp eye, things which had the breath of history upon them.

The early 19th century in India, as Upinder notes, was an ‘extremely exciting time for antiquarians’. Ancient texts began to be studied and translated; untrained but enthusiastic amateurs were tearing open mounds and discovering coins and relics; inscriptions in now all but lost scripts were being deciphered. Epigraphy and numismatics and archaeology engaged a whole lot of people, Europeans and Indians, many of them scholars. There were, in short, serious attempts at arriving at an understanding of India through exploring her ‘cultural and artistic heritage’: the British knew that they were not in this land as visitors or casual occupants of vast territories. An outstanding figure engaged in exploring India at this time was James Prinsep between whom and Cunningham a bond — ‘of intellect and friendship’ — had grown. Having learnt from Prinsep, but seeing himself as a field archaeologist, even while serving in the army, Cunningham kept observing, gathering, and writing.

What he was publishing all the time was Reports, meticulously kept notes based on his surveys and discoveries. And when he retired from the army, he prepared ‘a radical, well-crafted proposal’for a government-sponsored archaeological survey of northern India, and submitted it to the then Viceroy. Fortunately, the proposal was approved, and Cunningham was appointed Archaeological Surveyor, a role into which he threw himself with remarkable vigour. Site after site was identified, explored, studied: Pava and Kushinagar now; Taxila followed; Kaushambi and Shravasti came next. Within a matter of a few years, as many as 25 invaluable Archaeological Survey Reports based on field work had been prepared and published. A whole world was opening up.

A short while later, a momentous decision was taken at the highest level: there was to be an Archaeological Department of the Government, and Cunningham, who had left India in the meantime, was invited to return and take over as its Director-General. A new era was about to begin, as it were. Upinder Singh knows this area and has published on it (in her ‘Discovery of Ancient India’, for instance). But there was more round the corner. Not too long back she came upon a cache of documents: a completely unusual find in Kolkata. The Victoria Memorial Hall there had, with great imagination, acquired in 2005 this lot: 192 hand-written letters addressed by Alexander Cunningham in his own hand to his assistant, Joseph Beglar. The first letter was dated January 28, 1871, the year the Survey was founded, and contained an offer made by Cunningham to this young man of Armenian descent whose family had settled in India. Beglar, an accomplished photographer, took up the offer. These letters, filled with great riches and insights into the working methods and concerns of two archaeologists, are a virtual treasure. Upinder Singh has, with her own great imagination, published every single letter in this book — ‘The World of India's First Archaeologist’ —, even bringing in photographic images of some selected ones. Excitement mingles in these with dismay, light-heartedness with admonition, warmth and wit with earnest discussion. Bharhut and Sanchi run in and out of these pages; the Mahabodhi temple at Gaya begins to breathe a fresh air; measurements are given and corrected. As I said, it is a real treasure. One thing, however: the letters written by Beglar to Cunningham are just not here. Perhaps they will turn up some day, too, and perhaps Upinder will write another book.

What did Mirza Ghalib say about lost treasures, lost sights?

Sab kahaan kuchh lala-o gul mein numaayan ho gayin

Khaak mein kya sooratein hongi ki pinhaan ho gayin

[Not all, by no means all, have come up from below yet: a tulip here, a rose there

What sights, one wonders, must still be lying hidden in the ground under our feet!]

Join Whatsapp Channel of The Tribune for latest updates.